We relate to the world as much by image and symbol as by its tangible qualities. The more distant the reality, the greater the tendency to rely on myth and stereotype. These are rooted in our subconscious as archetypes -- a culturally derived idea or concept that resides deep in our minds as a visual construct loaded with meanings. By its nature, it is shared with many others in one's community. Foreign and alien lands are especially susceptible to this sort of primitive understanding. Direct knowledge of them is limited. Actual pictorial knowledge depends on access. Where unavailable, we fall back on those shortcuts provided by stylized imagery compounded of stories, films and our own imagination.

Everyone is susceptible to this phenomenon of being hostage to archetypes -- to varying degrees. It is not limited to the ignorant or uneducated. Consider the case of the ISIS or Islamic State that in recent months has swept through northern Syria and now Iraq -- a movement that has unfurled the banner of the Islamic Caliphate. That is, the theocratic rulership of the ummah (or at least the Sunni parts of it) whose last incarnation dissolved with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire almost a century ago. The ISIS has fired emotions while defying reasoned comprehension. This is due in part to its dramatic actions -- seizing cities, destroying a good part of the American trained Iraqi Army, proclaiming its audacious and fanatical ambitions, and committing grotesque atrocities. It also is due in part to the fragmentary nature of the information that we have about the movement, its followers and its mysterious leader. In this age of instant communication, there is scant film footage of the ISIS in action or reliable first-hand accounts of their doings. Moreover, the emotional residue of 9/11 and the fearful pictures of Islamist militants that have consumed us during the "War on Terror" years have made the psychological ground fertile for our agitated imaginations to conjure powerful visions.

So, what do we have? For the popular mind, the archetypical image is formed of ingredients drawn from film and newsreel and picture books. Color and vibrancy comes straight from Lawrence of Arabia and its sequels. The waves of ISIS warriors suggest the Arabs' camel cavalry charge against the surprised Turks in Aqaba. Robes flying in the hot desert wind; yellow, blue and green tribal flags hoisted high; blood-curdling cries of Allah Akbar; Faisal (Omar Sharif) and Auda (Anthony Quinn) spearheading the assault; the irresistible surge sweeping over the shattered defenders; scimitars cutting them down mercilessly. Only the blue-eyed, pale faced Lawrence (Peter O'Toole) resists transposition to Iraq. The two things missing are the Iraqi generals tearing off their uniforms and hopping into their Mercedes headed for Baghdad or the airport, and the masses of American heavy equipment abandoned to the marauders.

These graphic images prevailed because there were no alternative word pictures, much less video, of the actual scenes around Mosul and elsewhere. The only competing imagery came from the graphics displayed on TV and in the newspapers of the militants' advances.

Those maps feature arrows to signify direction of movement, flashes to signify battles, and a bit of color coding to signify towns and territory taken. They neatly reinforce old images impressed on our grey cells of distant battles from Napoleon to WW II. A different set of archetypal pictures. Instead of camel charges, our subconscious brings forward images of the Wehrmacht racing across the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa or the break-out at St. Lo. The distortion here is the imagining of large, highly organized armies engaged in conventional mechanized combat. In truth, the ISIS at the outset numbered in the thousands all told -- most of whom travelled in pick-ups and light trucks. Given these numbers, they could not possibly occupy vast territories -- even with the back-up of their tribal allies (who do not wear flowing robes or ride camels or wield scimitars). They seized key towns, roads and river crossings while leaving unoccupied great expanses of wasteland.

This misconception led many journalists and commentators to think in terms of armored divisions ready to pounce on Baghdad like Guderian's panzers on the road to Moscow. The fact that they did not do so was instinctively interpreted as due to the stout defense thrown up by government forces and the newly mobilized militias. Again, Zhukov extemporizing the defense of Moscow with the citizenry digging tank traps around the walls of the Kremlin. Nothing of the sort was going on. The ISIS was consolidating its gains and deliberately planning its next moves which certainly did not include a headlong thrust toward Baghdad. It was ignorance freeing the imagination to activate archetypical images and concepts. It took weeks for conscious minds to bend to realities which slowly displaced the upwellings from below.

Drawing on subconscious archetypes in order to explain a novel phenomenon about which there is little solid information almost always results in an exaggeration of its manifest characteristics. That is the fear reflex at work when the phenomenon is a menacing one. In the case of ISIS, the extremity of its cult-like fanaticism and cruelty did in fact match the imagined construct -- thereby, strongly reinforcing it. By contrast, the outfit's military potency was highly inflated.

Stunning successes on the battlefield fed the belief that it was far stronger than has proven the case. It was a form of deductive reasoning. Victories in the field meant that ISIS has to be very well equipped, profiting from tremendous elan, heavily financed and brilliantly led. They do enjoy some of those assets -- especially the elan, a steady money stream and skillful leadership of both a military and public relations nature. The sum of those assets, though, is less than what analysts and commentators were judging it to be. In any competition, one must take full account of the opposition in grading the performance of the winner. The Iraqi government side suffered from woeful commanders, low morale, unreliable intelligence, impaired political backing in Baghdad and inflated expectations stemming from their much ballyhooed training for years by the United States military.

The discrepancy between the archetypical image of ISIS, at least as a military force, and what it actually is capable of, was vividly demonstrated by the decisive, swift setbacks it suffered at the hands of the Kurdish pesh-merga around the Mosul dam and elsewhere along the margins of the Kurdish autonomous region. American airstrikes did help. But in truth they were little more than pinpricks that could have been shrugged off by an experienced, adaptive army of the sort ISIS clearly is not. In the event, those airstrikes sowed anxiety and defensiveness -- although not a panicked scattering of the Islamist host.

***

We have suffered mightily from the distortions perceptions of the enemy throughout the post-9/11 era. Imagery and thinking have been warped by a post-traumatic shock that conjured unrealistic and inaccurate conceptions of who al-Qaeda was. Here, the influence has been more enduring with more serious consequences. In the wake of 9/11, fear and dread ruled the minds of the public and policy-makers alike. The latter slowly, and partially gained a firmer grip on reality. They still, though, remain hostage to a conception that ascribes to the al-Qaeda network a unity, direction and capacity for far-reaching action that is way off the mark. It exalts what is a far more pedestrian reality. Doing so also serve the convenient political purpose of keeping public opinion pliable.

As with ISIS, the gross overstatement of what al-Qaeda could do was derived from their signal success -- the great tragic drama of the attacks on the WTC and the Pentagon. In hindsight, a fair judgment is that a small group of remarkably dedicated people managed to pull off the most stunning terrorist assault of all time due to a concatenation of factors: the gross failings of American intelligence and security agencies (especially the FBI); the discipline instilled in the perpetrators by the organizational and operational leadership based in Hamburg and New Jersey; and an awful lot of luck. So prosaic a reality was hard to accept -- in particular its assignment of blame to certain American persons and institutions. For that was at extreme variance with deep seated self-images of American prowess, competence and invulnerability -- all attributes of the country's collective archetype about itself.

It followed that al-Qaeda would be visualized as even more diabolical, more alien, more potent and more dangerous than it ever was. The group's uniqueness, moreover, seemed to defy placement within any imagined category -- conscious or unconscious. There was no archetype that could accommodate al-Qaeda. So, what we did was to create an archetype out of al-Qaeda. It was built mainly out of emotion and feeling with the conglomerate of fragmented bits of reality.

From the outset, there were two facets to the archetype -- ones that never have fit together easily.

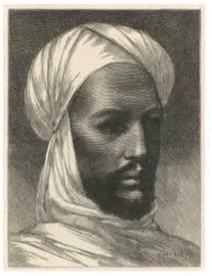

The first portrays religious fanaticism, primitive and merciless. That wild image nicely fit the persona of Osama bin-Laden: bearded, robed, turbaned with black eyes glowing like coals. If there was a precursor image it would be the Mahdi -- the Chosen One who arose like a desert sandstorm out of Sudan in the 1880s leading his Bedouin army in victorious battles that he vowed would restore the true Faith in Makka. The figure portrayed in Khartoum by Laurence Olivier who was undone by the haunting spirit of "China" Gordon whom he had killed.

This imagery was inadequate, though. Bedouins from the Sahara do not fly jet airplanes into Manhattan skyscrapers. The other facet of the emerging archetype formed the image of a highly skilled, disciplined organization with access to financing and technology. This al-Qaeda looked more like SPECTRE of James Bond villainy. Rootless and ruthless, everywhere and nowhere, driven by one man of singular force and will. Americans, at all levels, never could quite reconcile the two facets of the great Evil that has been al-Qaeda. The response, accordingly, has been bifurcated.

Archetypical shaped behavior entails roles for the protagonist. In the case of al-Qaeda that has meant stylized roles for Uncle Sam. One is that of the counter-terrorist fighter relentlessly hunting down the enemy in his own strange and alien world. It seems no coincidence that the desert camouflage uniform has become de rigueur for all grades of soldiers who have lashed themselves to the mast of the Global War On Terror. That includes commanding generals who wear this silly outfit even around the Pentagon. Civilians in Baghdad, too, adopted at least pieces of it. L. Paul Bremer III, our ill-starred Plenipotentiary in occupied Iraq, wore the desert boots as standard accessory to the 3-piece Brooks Brothers suit that he sported in the Green Zone. This sartorial identification with the sanctified role is akin to baseball managers squeezing themselves into players' uniforms -- with just about as much beneficial effect on the enterprise they lead.

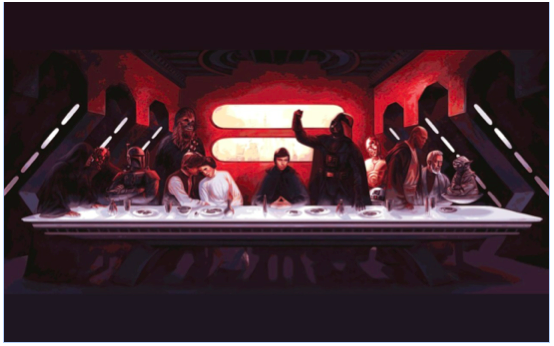

The second facet of the emerging al-Qaeda archetype did not as readily lend itself to tangible representation. Al-Qaeda leaders, whatever their attire, wielded power more in the manner of Wall Street CEOs than Bedouin tribal chiefs. Their prowess, if not their provenance, conveyed the image of the SPECTRE command center featured in a number of the Bond tales. Maybe that explains why General Keith Alexander, recently retired head of NSA, back in 2006 decided to configure his command and control center after the one modelled in Star Wars. Alexander took a personal hand in sketching out the design and insisted on hiring the Hollywood decorator who had created the original. The NSA high-tech approach to the GWOT thereby was made concrete and visually compatible with their conception of the mission. Near perfect imagery for the times: Osama bin-Laden as Darth Vader and Keith Alexander as the legendary Jedi Knight Obi-Wan Kenobi. Alexander was not known to wear a desert camouflage uniform in his space age headquarters. Archetype nonetheless -- the Force is always with the guy with the red-white-blue lapel pin.