Prior to the Great Recession, which lasted from December, 2007 to June, 2009, inflation-adjusted U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) peaked in the fourth quarter of 2007. It took 14 quarters to eclipse that level. By the third quarter of 2011, economic activity was finally back to pre-recession levels. Since the recession's end, we have been growing at a lackluster rate of a little over 2 percent. At times it has appeared as though we would break out of this sub-par rate of growth, but each time so far we have failed to do so. Whether due to poor weather, the threat of a government shut-down, a struggling Europe, the expiration of tax breaks, or the threat of war -- economic growth has, fairly predictably, stumbled to some extent in each year since the recession. Will we ever get out of this malaise?

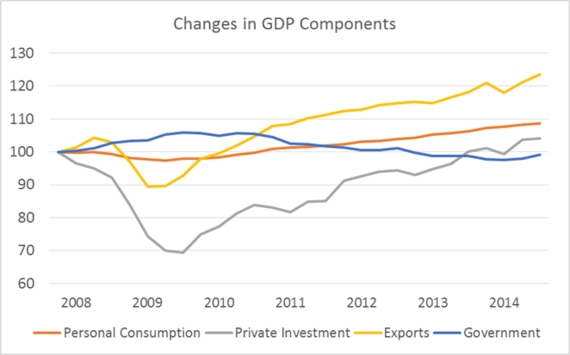

We thought it would be instructive to go back and look at how each component of GDP has fared since that pre-recession peak in GDP. Using inflation-adjusted numbers, we indexed each component of GDP to 4Q07 levels, beginning with a value of 100 for each. We graphically display the results below, followed by some commentary.

- The four major components of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) are 1) Personal Consumption; 2) Private Investment; 3) Net Exports; and 4) Government spending.

- It should first be noted that following a Keynesian increase in response to a deep recession, Government spending is currently running below the level of 4Q07. This is certainly a good thing for those of us worried about ballooning levels of government debt at a time when entitlement payments are set to expand dramatically. However, lower or even stable levels of Government spending would be a continued drag on economic growth. At some 18 percent of total GDP, the contribution from Government spending cannot be ignored.

- Personal Consumption, or consumer spending, has closely tracked the course of overall GDP. This is because consumer spending has accounted for 67-68 percent of total GDP on a consistent basis. Going forward, we suspect that consumer spending will continue to grow at a lackluster pace. Our expectations are based on a several factors. First, the labor remains weak, with part-time and lower-paying jobs contributing the lion's share of new job growth. Incredibly, median household income is now sitting at 1995-1996 levels. Although wealthier Americans have certainly done more than their share of earning and spending in recent years, we don't think the needle can move in dramatic fashion until and unless the masses become more confident in their earnings prospects. Secondly, rising non-discretionary expenses like health care and education are likely to eclipse the near-term benefits of lower gas prices. Third, consumer debt levels remain too high even though debt-service ratios are running at very low levels as a result of low interest rates. And finally, baby boomers are ill-prepared for retirement and must increase savings rates from their current low levels (relative to long-term averages).

- To track the third component of GDP, Net Exports, we decided to ignore Imports. We did so because Imports are a "contra account", which subtracts from GDP. We wanted to see how the change in Exports is affecting GDP rather than tracking the balance of Exports less Imports (which is always a negative number since we import more than we export). Having clarified that, it is easy to see that Exports have had a large positive impact on GDP in recent years. In fact, Exports have gone from comprising 11 percent of GDP in the 4Q07 to over 13 percent in the 3Q14. Why is this important? Because a slowing global economy and a sharply higher dollar will undoubtedly have a negative impact on Exports going forward.

- Finally, Private Investment is the component of GDP that dropped in the most dramatic fashion during the recession. This category includes business spending on plants, property, equipment, software, inventories, etc., as well as investments in residential real estate. We all know how bad the housing market was hit during the recession, but it is the non-residential portion of Private Investment that offers more insight for our purposes. We have spoken at length about how corporate profit margins are running at unsustainable high levels. In fact, margins are running some 50 percent higher than long-term averages. One of the reasons for the disparity is that companies have been reluctant to invest given an uncertain demand outlook. Accordingly, corporate managers have kept headcount down, payroll increases modest, and investments in PP&E to bare minimums.

But there is another reason, aside from an uncertain demand environment, that corporate investments are still running at low levels. An article in the Wall Street Journal ("U.S. Margins Defy Doom of Profits", by Justin Lahart) says, "Today's wide profit margins probably owe a lot to changes in the investing climate. Those other two mysteries -- persistently low interest rates and inflation - have led to profound changes in what many investors look to stocks for." The author goes on to say that given the lack of securities offering acceptable levels of income (ie, bonds), many investors have turned to stocks for income. Therefore, he says, investors seeking income "are more apt to reward managers who generate and return cash to shareholders over managers who are looking to reinvest and grow."

It's a nice theory I guess. But my contention would be much simpler. Corporate managers are just doing what works. Following the financial crisis, investors are not in the mood to take big risks. They would rather have the certainty that comes with higher dividend payments and increased stock buybacks. And as Lahard rightly points out, "the growing clout of activist funds" is there to keep management teams in line if they do anything crazy like make long-term investments rather than returning capital to shareholders. But this is a very dangerous cycle. If companies, in the aggregate, are unwilling to invest in the things that drive long-term growth, how are we to expect much better growth in the future?

As you can likely glean from the above, an acceleration in economic growth from the ~2 percent pace since the recession may be harder than most believe. As difficult as it may be to admit, neither the willingness and ability to spend, nor the appetite to invest, are likely to increase in dramatic fashion over the intermediate term. We suggest lower expectations. The fragile recovery continues-fragilely.

Peace,

Michael