Ever since the global financial crisis central bankers across the globe have become increasingly fearful about the prospect of widespread deflation. These fears have been magnified exponentially by the more recent crash in commodity prices. Dramatic price adjustments for everything from copper to corn to oil signal, in no uncertain terms, that supply exceeds demand for many goods (and some services) in the global economy. And Economics 101 tells us that if supply exceeds demand, a downward price adjustment is forthcoming. Compounding the fears about deflation in the US has been a dramatic rise in the value of the US dollar, which has caused import prices to plummet. Because the US is a net importer, the effect of lower import prices has not been trivial. So, the combined effect of lower commodity prices and a strong dollar has led to disinflation, which simply means that the rate of inflation has fallen. Can we expect, and should we fear, a drop into deflationary territory?

Focusing on commodity prices for now, there have been spirited arguments over the primary source of the mismatch in supply and demand. Is it the case that the world's capacity to produce commodities has simply outpaced the world's need for these commodities? Certainly this is a contributing factor within the energy markets, where new technologies such as hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling have led to dramatic increases in oil supply, especially in the US. But what about other commodities like copper, steel and agricultural products? How much of the price declines in these commodities is due to increased production capacity as opposed to a softening in demand? This is the $25,000 question. Identifying the source of the supply/demand mismatch is imperative if we want to determine the implications of commodity-induced price declines.

After all, why are central bankers so concerned about deflation? Shouldn't we all be celebrating the fact that prices have dropped, reducing expenses for struggling consumers and businesses across the world? Unfortunately, it's not that simple. There are three major reasons why deflation is a beast to be avoided at nearly any cost, at least in the minds of central bankers. The first is simply the signal that lower prices transmit to consumers and businesses. Falling commodity prices, in particular, often serve as a canary in the coal mine for the economy at large. When commodity prices fall, it can be a sign that demand has dropped off. Lower demand, in turn, could be a sign that the global economy is faltering and headed for recession. It is important to keep in mind, though, that demand (and not supply) must be the primary source of the supply/demand mismatch. As noted above, this is a big caveat in today's rapidly changing global economy. If it is determined that lower demand is the primary culprit, then lower prices can serve as a negative feedback loop for all economic participants, creating a self-reinforcing decrease in confidence. If a technology-induced increase in supply is responsible for lower prices, it can be a boon to economic growth.

A second reason to be fearful of widespread deflation is that it causes consumers, businesses and governments to defer spending and investment decisions. Think about it. If you can buy a new lawn mower for $500 today or $400 in six months, would you buy it today? If your company could hire a new employee at $15 an hour today or $13.50 an hour next year, would your company wait to add that new person? If your state government can save 5% on materials for the construction of a new bridge if it waits a year, do you think it would do so? Now imagine these investment and consumption decisions being made across the entire economy. Deferred consumption and investment decisions, in aggregate across an economy, can put a serious dent in economic output. So, in a nutshell, inflation encourages current consumption and investment while deflation incentivizes people to defer those decisions. This is perhaps the primary reason why the Fed has an inflation target of 2% rather than 0%.

Another negative side effect of a deflationary environment is that falling prices make it harder for borrowers to pay back their debts. This problem would be especially acute right now given the fact that economy-wide debt has only increased during the course of the recovery from the financial crisis (which itself was caused by too much debt!). Imagine if you have a $250,000 mortgage on your house, and you are making monthly payments of principal and interest. Let's say the interest rate on the mortgage is fixed at 4.0%. You work for the federal government and get annual pay increases called "cost-of-living adjustments", or "COLAs". All of the sudden, a drop in price levels has reduced your annual COLA pay increase to zero (or even lower!). You can certainly try to refinance your loan, but there is a limit to how low this rate can go (and you may not qualify). Compare this to a scenario whereby inflation, and therefore your annual pay increase, is 3% per year. Your 3% annual pay increase (or perhaps more with a promotion) will make it much easier to make your fixed mortgage payments while continuing to pay down principal over time.

Deflation also makes it much harder for businesses and governments to service their debt. Remember, businesses have been taking on large amounts of debt to buy back stock in recent years. The federal government, for its part, has racked up an enormous $18 trillion in debt, including intragovernmental holdings. As deflation cuts into the incomes of businesses and consumers, everyone will find it much harder to pay down their huge amounts of debt. Businesses will see their profits decline, and depressed tax revenue will only exacerbate the federal government's long-term fiscal crisis. Don't think for a minute that the Federal Reserve isn't aware of the Treasury's predicament. The Fed wants everyone, including the federal government, to be able to repay their debts with inflated dollars.

So, if you combine the negative effects above, you can see just how dangerous a deflationary cycle can be. Deferred spending/investment decisions lead to lower aggregate demand for goods and services. Lower demand means companies generate less revenue and income. Lower corporate revenue and income results in reduced investment in plants, software, equipment, employees, and pay increases. Reduced employment opportunities and lower wage growth cause a decrease in confidence and spending as well as lower disposable income to service debt. Lower business and consumer incomes will lead to lower federal tax revenue. And the cycle continues. The poster child for this vicious cycle is Japan, which has been struggling to fight off deflation for a couple of decades now.

- Penalize savers

- Encourage profligate spending

- Encourage the assumption of more debt

- Pull forward future demand

- Destroy retirement savings accounts

- Destroy pension funds

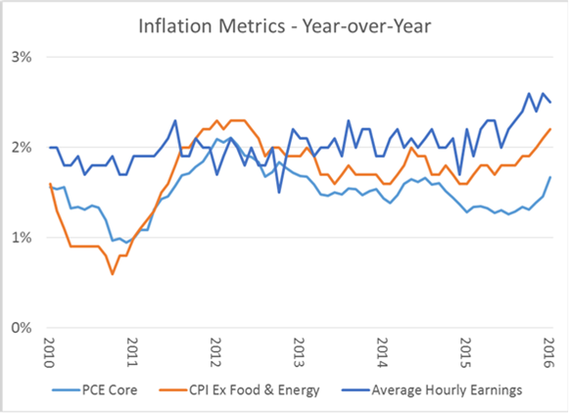

I hope I've sufficiently hammered home the idea that policymakers, economists and investors should not hope for a deflationary environment. But given its negative impact on the economy, should we as investors be worried about deflation? Not according to the Fed. Chair Yellen and other participants continue to say that the effect of lower energy (and other commodity) prices and a stronger dollar on overall inflation will be transitory. If we look at the individual commodity prices, it does appear that that price levels, especially for energy, have bottomed out and started to rebound. I have no idea if the rebound will continue or if new lows lie ahead. But in ending QE and beginning the interest-rate hikes, the Fed has felt comfortable enough to essentially ignore falling commodity prices and a stronger dollar. If we look at some of the key gauges of inflation in the chart below, it indeed seems to be the case that inflation is picking up. So for now, at least, it appears we have escaped Japan's fate. Investors are right to cheer the news.

Source: Bloomberg