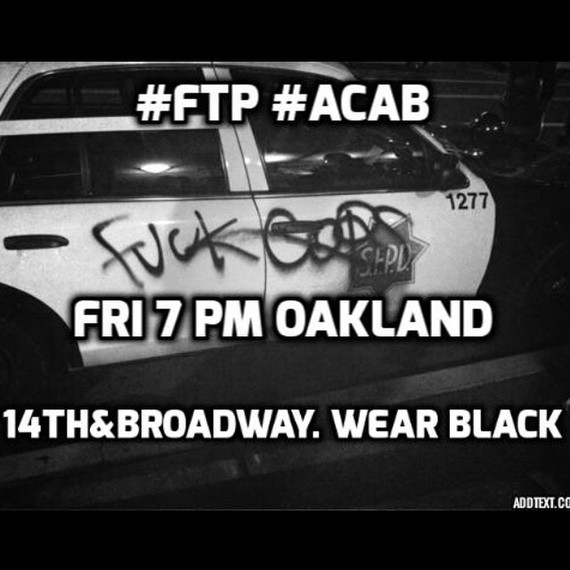

Part of the police accountability movement sees police as the enemy, often under the slogan "Fuck the Police." But the police we can taunt on the street are not the real problem. Their management, beholden to that fraction of "the one percent" which actually wields political power, is, as is the system they are a part of. Targeting police in general — who are but the human cogs in an oppressive system — is both a diversion and a way of making matters worse.

I get the contrary view, having studied on a campus occupied by squads of riot-clad deputies, dodged a baton, run from a careening patrol car used to disperse protesters, faced an FBI agent's perjury, etc. But this is small stuff compared to outrages so many people of color face or risk regularly; there is much that those of us who are in white skins and not poor can't imagine. So I have no right to criticize anything about spontaneous expressions of outrage from communities that are truly oppressed. But a lot of the "FTP" folks in my area are young whites, and the FTP stance also exists among those of us working for change long term, an orientation the effectiveness of which I question.

That said, here's how I judge any political action:

- do its stated aims accord with the needs of the 99% or some community within it?

- does it actually promote those aims?

- does it do so in a way that (a) improves popular understanding of the problem and its causes, i.e., develops more support and (b) helps empower the communities involved?

Certainly any opposition to the epidemic of police violence against people of color meets the first criterion. But spitting on returning veterans did not help end the Vietnam War, and I believe treating the cops we face as enemies only provides an emotional outlet, while diminishing our ability to compel changes.

Cops' Loyalties Can Shift

Dr. Gene Sharp's research shows that any undemocratic system has "pillars of support," such as the state apparatus in general, the police, the media, and a sector of the clergy. Hundreds of case studies by both him and Prof. Erica Chenoweth show that the pillars of support for an unjust regime can be split, with major parts defecting. Whether that happens depends largely on the strategy of the opposition.

Police officers are recruited mainly from the working class and are working people. Officers do tend to have traits that would interfere with warm community policing, both because of who is drawn to police work and the culture molded by the job as it is structured. And racism is a huge factor. But I doubt that many enter the field primarily because they want to crack heads, shoot people of color, or gas protesters. Many may want some authority (like many of the rest of us), but they also want good jobs, and they are interested in doing public service.

Police officers are recruited mainly from the working class and are working people. Officers do tend to have traits that would interfere with warm community policing, both because of who is drawn to police work and the culture molded by the job as it is structured. And racism is a huge factor. But I doubt that many enter the field primarily because they want to crack heads, shoot people of color, or gas protesters. Many may want some authority (like many of the rest of us), but they also want good jobs, and they are interested in doing public service.

There has always been huge conflict there between blacks and Irish immigrant population (imported to work the steel mills, auto plants etc.) Now into 2nd generation and 3rd generation it is ingrained in behavior and in systems. Hard to describe to somebody who didn't grow up there. It is bigotry of a different kind that goes beyond classic southern bigotry. Irish and blacks were competing for housing/jobs in S. St. Louis in the old days. The Irish were often in the police, the power elite. When they spread out to the suburbs, the conflict continued. Add to that southern KKK and that bigotry, whew. It is a culture of shocking disrespect/total disregard for all people.

-->

Police are still people, human, with hopes, fears, and reactions to good or ill treatment. If you doubt that, talk to a couple of them about their work, how they feel about the controversies, or what it's like to do crowd control.

It's About Policy

How police treat citizens depends on how they are trained and managed. Joseph McNamara told an L.A. Times reporter that, while on patrol in Harlem, he had been in 150 situations where policy would have justified his firing on a suspect, but he never had. He later served as chief in Kansas City, Kansas, and then in San Jose, California. The story reports that a Kansas City cop

shot and killed a 14-year-old black fleeing a burglary. McNamara attended the boy's funeral and issued a directive that police could shoot only when a suspect endangered others' lives. [Referring to fallout from that action], he says, "One of the things that occasionally gets under my skin is (when) people say, 'You're a controversial police chief.' What in the world is controversial about saying the police shouldn't use more force than they have to? We have a fundamental duty to protect human life — we shouldn't be taking a human life unless it's absolutely necessary."

McNamara's recent obituary quoted a former colleague: "Joe was about preaching accountability and the fact you had to answer to the community. It can't be an 'us-against-them' attitude. It had to be a 'we.'"

Similarly, the guy with the #BlackLivesMatter sign in the photo is Chris Magnus, Chief of Police in Richmond, California. Other officers from his command staff participated in the protest as well.

Magnus' eight years as Richmond police chief have seen a sustained reduction in violent crime that has rarely been matched in other cities that have experienced seemingly intractable violence related to gangs and chronic unemployment. . . . Magnus' community policing programs . . . include forging strong bonds with community members, church leaders, and young people.

San Jose's record under McNamara was similar.

Policies make a difference. "[C]ities that have instituted strict guidelines on circumstances in which officers can fire their guns have seen a significant drop in the number of police shootings of civilians." (Weitzer & Tuch, Race and Policing in America, Cambridge Univ. Press (New York: 2006), p. 47.)

Citizen safety must join the usual overarching emphasis on officer safety in training and policy. Philadelphia's Police Commissioner says that at times of protest, "before roll call, we read the First Amendment to our officers, reminding them people have a right to demonstrate." There are ways to train people to recognize and largely set aside their biases towards people who are ethnically different, biases which we all have. Laurie Robinson, who co-chairs Obama's policing task force (which will have little impact), adds that training should include

the whole issue of how to de-escalate confrontations. We've seen in many of the incidents that have sparked controversy that de-escalation could have been a very helpful skill for the officers to have had. Oftentimes, in training, there's a lot of technical training, how to drive cars, how to shoot. But people skills are so critical.

So permitting — and encouraging — police violence is a policy choice. Change requires amassing powerful forces to target policy-makers, who have good reason to resist it. Targeting their pawns increases cops' solidarity and makes it impossible for those who don't like what is going on to talk to their colleagues or covertly or overtly help our cause. It also alienates people who don't understand the issue, whom we could reach by crafting campaigns with targets and demands that help build the broad base of support that is our only hope for creating change.

More on that in another post . . .

Photo Credits: (1) Posted on Occupy Oakland's website. (2) Posted on Richmond P.D.'s Instagram page. (3) Tim Hussin for The San Francisco Chronicle, by permission. That baton broke his camera lens seconds later.