Specialist Misha Pemble-Belkin (l.) and fellow soldiers from Battle Company, 173rd US Airborne during a firefight at Outpost Restrepo during combat in Afghanistan's Korengal Valley. Korengal Valley, Afghanistan, Kunar Province. 2008. A film still from the documentary RESTREPO by Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger. Photograph © Tim Hetherington

Who wouldn't want to spend the good part of fifteen months at a hot, dusty, flea-bitten outpost, precariously perched on a mountain ledge overlooking a tree lined valley that provides cover for people who shoot at you daily? Oh, and there's no electricity, no internet, no TV, no running water, no bathroom, no heat, no privacy and no one from the opposite sex. No comforts at all. Not even a chair. Just unremitting boredom broken up by whizzing bullets that ping the dust long before the sound makes it to you.

Not the stuff of romance that typically fills the lines at Army recruiting offices but this alluring scenario was too good for a pair of seasoned war correspondents to pass up. Author and journalist Sebastian Junger and photographer/journalist Tim Hetherington convinced Vanity Fair, the news arm of the American network ABC, and the US Army that it would be a good idea to send the team to the Korengal Valley -- "the deadliest place on earth."

RESTREPO filmmakers Sebastian Junger (l.) and Tim Hetherington (r.) at Outpost Restrepo. Korengal Valley, Afghanistan, Kunar Province. 2007. Photograph © Tim Hetherington

"I wanted to be with the best unit in the worst place," said Junger, who's reported from Afghanistan on and off since 1996 and from numerous other war zones.

As Captain Kearney says in the film that resulted from their experience, "the road ends at the Korengal outpost and where the road ends, the Taliban begins."

Junger's partner in this adventure to the edge of the empire covered the civil war in Liberia, the wars in Chad, Nigeria, Sudan and the post conflict zones of West Africa. Hetherington saw this assignment as "kind of a distillation of our war experiences over the ten years we've been doing this," he said. "This is what we've done, we know what to expect."

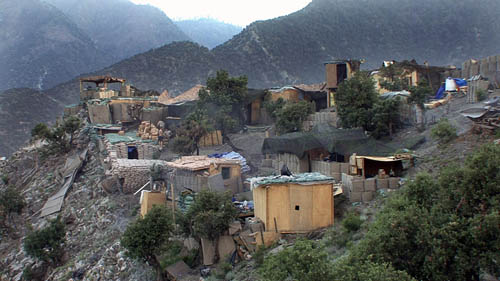

Outpost ("OP") Restrepo. Korengal Valley, Kunar Province, Afghanistan. 2008. A film still from the documentary RESTREPO by Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger. Image © Outpost Films

Their experience embedded with one platoon that's been tasked with securing a hilltop combat outpost as part of the Army's offensive in Kunar province, near the Afghan/Pakistan border, is the subject of their riveting new documentary, Restrepo, winner of the Grand Jury Prize at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival.

This 94-minute film takes the audience inside the non-too glamorous life of the foot soldiers in a dangerous yet beautiful setting. "It was an anti-paradise," said Junger, "Everything young men enjoy wasn't up there and everything they didn't like was."

Junger and Hetherington toted small HD cameras with them because they had a deal with ABC to supply footage but they also wanted to make a film. They divvied up the camera chores to insure they got enough coverage.

"We basically did everything together, put it in a pot, shook it up and it came out," said Hetherington.

The production team remains in the background while providing a window into this "anti-paradise." Viewers are front and center with the soldiers of 2nd Platoon from the moment they helicopter into the Valley. We stay with them during their fifteen month tour as they're shot at, build their remote outpost, suffer the death of friends, witness the human cost of counterattacks on villagers, while away the boredom strumming guitars, engage in horse play and finally pack their rucksacks to hike back to the copters waiting to take them home.

Most embedded reporters stay with an outfit for two to three weeks. Exactly what Mark Boal did for a Rolling Stone assignment that inspired his feature film writing debut, The Hurt Locker. Junger and Hetherington took the deep dive approach in an attempt to create a more in-depth view of life during a complete tour of duty in a combat zone.

The platoon was assigned to set up one of a string of outposts that have been affectionately referred to by some, as "bullet sponges" or "Taliban magnets" that draw fire from the insurgents and allow the American forces to use their overwhelming superior firepower to eliminate them one by one. Embedding in the "sponge" allowed the crew to capture plenty of chilling "bang bang" scenes. Sometimes occurring four or five times a day. The filmmakers are right there as the platoon takes fire and in the ensuing chaos we see the soldiers scramble to locate the enemy and return fire. We stay in the mix as they leave their spartan confines to venture out on patrol. Without the rock-filled plastic battlements to protect them they are exposed from every angle. And when the inevitable attacks come, Junger and Hetherington capture every potentially heart stopping moment.

But it's the little human moments that occur during downtime that began to excite Hetherington about the unique possibilities of the film they were making.

Specialist Misha Pemble-Belkin (l.) and Ross Murphy (r.) of Battle Company, 173rd US Airborne relax at Outpost Restrepo. Korengal Valley, Afghanistan, Kunar Province. 2008. Photograph © Tim Hetherington

"I understand my work is about building links to an audience," Hetherington said. "How do I connect them to a conflict in Liberia or Afghanistan? Moral outrage is not enough. Pictures of dead West Africans are not enough. Witnessing is important, but to move an audience we have to connect in a way that shows them their sons and their brothers" as complete human beings with a range of emotions.

The soldiers' candid dialogue in the field, and the forty hours of interviews shot after they'd returned to their home base in Italy, bring us into the story with their own words. We hear twenty-five year old Corporal Pemble-Belkin tell us his hippie mother wouldn't let him play with toy guns, not even a squirt gun, as we see his face light up while he energetically sways a tripod mounted 50-caliber machine gun back and forth, up and down. But he also says that he doesn't want to worry her so in his most recent letter home he didn't include news about the deaths in the platoon or their upcoming dangerous mission.

On that mission down the hill and into the villages, the platoon stops to question a young man who tells the translator, "If we let you know about the Taliban we will get killed."

"A lot of Afghans feel caught between two realities," said Junger. They remember the "bloodbath" of the '90s after the Soviets pulled out. They also remember greeting the Americans as liberators after we toppled the Taliban but they saw us get distracted by the war in Iraq and not carry out the hoped for reforms in their country.

While telling the story of the soldiers, the filmmakers also wanted to convey "the nuanced sense of Afghans caught in-between," said Hetherington.

Captain Dan Kearney of Battle Company, 173rd US Airborne meets with local Afghan elders in the Korengal Valley, Kunar Province, Afghanistan. 2008. A film still from the documentary RESTREPO by Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger. Image © Outpost Films

We do experience the palpable disconnect between the U.S. troops and the villagers who sit together during several Shuras (meetings with elders) but we're never given the back-story about who the locals are and why they met our presence in their isolated, mountainous lair with lethal hostility.

I wanted to better understand the origins of the mission in the Korengal so I called James Fussell, who'd been on the ground as a Special Forces Major in the area and has co-authored a report for the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) about our efforts in Northeast Afghanistan. "We were not well received by the Korengali," said Fussell.

The U.S. came in offering to build roads to connect the villagers to the outside world and we expected to be greeted with open arms as we had in other parts of Kunar province. The villages in the remote Korengal are inhabited by a fiercely independent people ethnically distinct from the Pashtuns -- the dominant ethnic group in Afghanistan. They speak a separate language "called Korengali or Pashai" and "are generally suspicious of outsiders, including other Afghans," according to Fussell.

"The Korengali have been able to maintain themselves for thousands of years because of their isolation from the Pashtuns who live in the lower levels of the valley and who they feared might conquer them if a road was built," said Fussell.

They also feared losing the very lucrative monopoly on smuggling timber if a road was built. President Hamid Karzai had tried to regulate the timber trade before and this also alienated the Korengalis. The smuggling continues and it pays for the insurgency.

"We didn't understand. We were there trying to build a road and they attacked us," he said.

As more Americans started to die it became less about road building and it became "hallowed ground," in Fussell's view. "The decision makers (including Colonel Ostlund commander of the 173d Airborne Brigade that included the platoon featured in the film) had lost too many men and no one wanted to be the officer who was going to lose the Korengal," said Fussell.

Then the law of unintended consequences takes root. "The Taliban didn't set up shop until we arrived," he said. The Korengali invited them in because they thought, "My enemy is their enemy," said Fussell.

Specialist Kyle Steiner of Second Platoon, Battle Company, 173rd US Airborne at Outpost Restrepo. Korengal Valley, Afghanistan, Kunar Province. 2008. A film still from the documentary RESTREPO by Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger. Image © Outpost Films

Our good intentions devolve into a counter terror operation, "find the bad guys and kill the bad guys," he said. Which is where we are when the film begins as the troops stake out their position "about half-way down the six-mile valley." The remainder of the valley is controlled by the insurgents.

The film doesn't delve into discussion about the policy decisions that sent the soldiers to this dangerous post or the arguments surrounding this costly and seemingly unending war.

"I wasn't interested in writing about the politics or the geopolitics of the situation," said Junger. "I went in as a blank slate."

The end result of Junger's and Hetherington's approach is a film about all wars. A film that transcends Outpost Restrepo as it puts you in the boots of these soldiers who spent every day, for fifteen months, trying not to do anything to get one of their brothers killed as they counted the days remaining before they could go home.

Ironically, Colonel Ostlund, the area commander in the Korengal, is one of three officers who received an official reprimand stemming from the deaths of nine American soldiers and the wounding of 27 others during an attack at another base in Kunar as the 15-month tour was coming to an end. It was alleged he and the other commanders had become "complacent."

The fierce fighting continued until Outpost Restrepo was abandoned as U.S. forces pulled out of the Korengal Valley in April of this year.

"We were protecting a population that didn't want us and building a road that wasn't going anywhere. It didn't make sense," said Fussell.

The experience in Korengal should teach us that even if you have the best intentions but you don't understand the cultures you can cause more problems than you solve. The human costs are enormous. This film and the outpost were named in honor of the platoon's medic, PFC Juan Restrepo, who was killed in combat in the Korengal Valley.

The film hits theaters in New York and Los Angeles starting June 25 and rolls out across the country after that.

The National Geographic Channel will air Restrepo in the Fall.

Restrepo

94 minutes - Rating R

A National Geographic Entertainment presentation

An Outpost Production In association with National Geographic Channel