Purim is upon us and this year (2016) it falls during the Christian Holy Week. In some ways these two holidays could not seem more different. The Jewish holiday of Purim is celebrated by the reading of the Book of Esther, feasting and drinking. It commemorates how the Jewish heroine Esther saved the Jews of Babylon from the evil Persian minister Haman who sought their destruction.

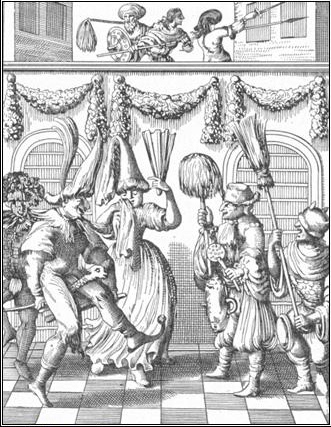

Purim celebration. Engraving. Johann Leusden, Philologus Hebræo-Mixtus, Utrecht, 1657. Published before 1923 and public domain in the US.

Holy Week is the last week of Lent during which the final events of Jesus's life (including his entry into Jerusalem, the Last Supper, and the Crucifixion), often called the Passion of Christ, are commemorated. Both holidays are based on biblical stories in which one group is persecuted by another. For Christians, the story of the Crucifixion is the tale of Jesus' suffering at the hands of the Pharisees, and for Jews, the story of Esther is the tale of Jewish persecution by the Persians. Violence is central to both these events as recorded in the Bible.

During the Middle Ages the celebration of Easter was often associated with violence, as Christian celebrants participated in Passion plays and even sometimes in masses in which actors or priests reminded them in often vivid detail of the suffering of the last days and hours of Christ's life. Jews across Europe often found themselves the target of misguided Christians who blamed them for the actions of the biblical Jewish figures, the Pharisees. In his 1998 study, Communities of Violence, David Nirenberg offers several such cases of Christian violence toward Jews across southern France and Spain. Purim celebrations similarly included remembrances or reenactments of violence. John Tolan ("The Rites of Purim" in Ritus Infidelium 2013) has shown that during the Late Antique period Purim celebrations sometimes featured the burning of effigies of Haman, the Persian minister who sought the Jews' destruction in the story of Esther. Elliot Horowitz (Reckless Rights 2006) further shows that during the Middle Ages carnivalesque Purim celebrations, during which the Jews raucously commemorated how the Jews of Persia were forced to protect themselves from Haman, sometimes gave rise to a type of Black Legend falsely attributing to Jews acts of violence like the murder of Christian children or the desecration of the host or cross.

But both Purim and Easter also offer tales of hope and redemption. Purim celebrates a powerful woman figure who risks her life to save her people without bloodshed. Esther's position in the Persian court was a dangerous one because she was a member of a religious minority and her husband the king was unstable. Nevertheless, in the Book of Esther she confronts him regarding the plan he has adopted on the advice of his minister Haman, convincing him to direct his anger at Haman rather than the Jews. Esther's intelligence and social savvy--her ability to survive and manipulate the complex mores of the Persian court to her advantage--offers a model for Diasporic Jews living as a minority in nations where most people are members of another, often hostile faith.

The week preceding Easter is celebrated by Christians as Holy Week. The focus of Holy Week is the suffering of Christ in the days leading up to his crucifixion. It culminates in Easter, the celebration of Christ as the Messiah. Across Latin America and Spain Holy Week commemorations include processions and public festivals. Floats depicting scenes from the last days of Christ's life, as well as images of Christ and Mary are taken from the local churches and carried throughout town/city, often accompanied by bands and participants dressed for the occasion.

By Migvazgar (semana santa 2009) via Wikimedia Commons

The festivities culminate with the lighting of the Paschal candle on the Saturday before Easter. This candle symbolizes hope and the Christian belief that Christ offers redemption from sin and the opportunity for survival in the afterlife. The Easter celebration marks Christ's resurrection and is celebrated by ending the Lentan period of fasting with a feast.

Feasting and fasting are also central in the story of Esther as we have inherited it in both the Jewish and Christian traditions. In both the Jewish and Christian accounts of Esther she and her fellow Persian Jews fast for three days before she invites the king to a banquet feast which lasts for two days. Over the course of the banquet King Ahasuerus is reminded of how a Jew, Mordechai, Esther's relative, saved him from an assassination attempt and he also finds out about Haman's evil intentions toward Mordechai and the Jews. As scholars such as Miriam Bodian (Dying in the Law of Moses, 2007) and Emily Colbert Cairns have shown, in commemoration of these events and in honor of the figure of Esther who saved the Jews of Persia from persecution, Spanish Jews who had been forced to convert to Christianity continued to observe (from the fifteenth until at least the seventeenth centuries) the three day feast period in honor of Santa or Reina Ester.

Esther emerges as a model of hope for the secret Jews living under intolerant Iberian Church and royal officials in Spain and Portugal and their colonies. The members of the Carvajal family in what is today Mexico observed fast days for Queen Esther ("la Reyna Ester") as they desperately sought to keep their Jewish identity, living in constant fear of the Inquisition. They were ultimately unsuccessful and on December 8, 1596 were burned at the stake in a public auto-da-fé in Mexico City.

Both Purim and Easter offer tales of persecution and hope for people of different faiths living together in often tense and sometimes openly hostile times. In both, religious minorities are the victims of persecution and injustice. Esther and Jesus both, though, become symbols of hope and models for others facing such violence and persecution.