Part One

Thirty nine years ago, I walked out of Warner Bros.' London offices with a knot in my stomach.

It was late and chilly on Wardour Street, a good three miles to the flat I was renting in St. John's Wood, yet I desperately needed that walk to get a grasp on the emotions churned up by the film I had just screened. It was a response one hopes for in the movies, when something completely transports you to another world, and you need time to get yourself around the film before restoring your own reality.

The movie was The Terminal Man, British director Mike Hodges's third feature and his first as producer on a major studio project. He had freely adapted the best-selling Michael Crichton novel into a chilling warning of technology gone amok in the name of benefitting humanity. In the process, he presented a searing indictment of medical and scientific arrogance.

The plot concerns a computer expert (George Segal), whose involuntary homicidal tendencies can only be harnessed by an experimental implant that controls his manic urges. The film was unrelenting, gripping and filled with technical achievements, from the 28-minute operation, researched and orchestrated in detail, a pristine production design that looked like a black and white movie, augmented by grays and silvers, and a haunting use of Glenn Gould's forlorn piano playing of one of the Goldberg Variations.

Hodges had made a Frankenstein for the modern age that pierced your mind and kicked you in the gut. It was also a film in trouble. The Terminal Man had just opened in America to misunderstood reviews and disappointing business. A U.K. release was now questionable.

I was at Warner Bros. implementing an innovative distribution project, adapting U.S. marketing methods to the release of films that were deemed unsuitable for European audiences. It was a consuming job, proposed to Warner Bros. chairman Ted Ashley by Stanley Kubrick, with whom I had closely worked on 2001 and A Clockwork Orange.

Challenges were what intrigued me and this was no exception. The project was also a political hot potato, as it was funded by a corporate budget, independent of both the international marketing/distribution apparatus yet having to work with both in order to achieve anything. And I was already doing double duty as Malcolm McDowell had insisted I handle O Lucky Man!, his new film directed by Lindsay Anderson, another original, demanding work which created its own set of marketing problems.

Walking past Marylebone Road, I had a feeling of dread that The Terminal Man could quickly disappear after seeing the U.S. advertising campaign, which positioned it as a mediocre science fiction effort, with a running George Segal floating against a backdrop of electrical impulses and primitive computers.

This wouldn't be the first Hodges film to suffer from a U.S. marketing botch-up.

I was publicity director at MGM when his first film, Get Carter, was released in 1971. It was MGM's only exciting movi during the Jim Aubrey regime of Brotherly Love, Kansas City Bomber and Green Slime.

We argued for a class, platform release for this hard edged dissection of British criminal morality, set for the first time in Northern England -- not London -- but the studio saw it as a B movie and tested it on Hollywood Blvd rather than the college-centered cinemas in Westwood. Aubrey, known as "The Smiling Cobra," insisted that general audiences were incapable of understanding the Newcastle accent and Hodges had to revoice several scenes.

Though singled out by Pauline Kael as a new kind of study in violence, it quickly played out on the action/drive-in circuit. But it became an immediate hit in England with a classy character-driven campaign and is now recognized as not only one of Michael Caine's signature performances but one of the best British films ever made, the British equivalent to The Godfather.

Hodges second film, Pulp, was a black comedy also starring Caine and an eclectic supporting cast headed by Mickey Rooney, Lizabeth Scott and Lionel Stander. It was given a one-week filler run in Los Angeles by United Artists, who were waiting for the prints to dry for their Christmas release, Man of La Mancha. By the end of 1973, after a booking at a small NY cinema, Pulp was named one of the year's ten best films by Vincent Canby in the New York Times and Jay Cocks in Time Magazine.

The mishandled pattern was continuing with The Terminal Man, Hodges's most ambitious film. Warner Bros' European offices were not interested in releasing it after the U.S. results. But the film was now in my blood and it needed something positive. I submitted it to the London Film Festival. The British executives thought me crazy. "It's too cold and upsetting for audiences."

Hodges had already heard that criticism from Burbank, aside from Warner Bros. co-chairman Frank Wells, who was a lone supporter, and had reluctantly acquiesced to

to add an opening exposition scene so that audiences would have "Someone To Root For."

The London Festival's influential director, Ken Wlaschin, responded immediately and gave The Terminal Man a key Sunday slot at the festival's biggest venue, the Odeon Leicester Square. As the sell-out audience of 2000 walked into the bright afternoon sunlight, they looked hypnotized; there wasn't a sound.

Despite its festival acceptance, British distribution still refused to release it. I called Kubrick, who wielded enormous influence at Warner Bros. after the success of Clockwork and his astute analysis of distribution practices. He was also a Hodges' admirer -- "Any actor who sees Get Carter will want to work with him."

I explained the situation, said it needed a different campaign, but before I could continue, he interrupted with, "I've already seen it and it's terrific."

I thought his endorsement would be enough to change the U.K. decision but a few days later Stanley said he couldn't budge them. It was an internal matter and my international marketing brief did not include Great Britain. The Terminal Man scared them.

My double duty with O Lucky Man! and the marketing program required 24/7 attention. Several films had been selected for territories that had refused to release them. My mandate was to inventively turn around Blume in Love in Sweden and Enter the Dragon in Italy. But a Terminal Man campaign was already brewing in my head.

Internal politics eventually freed me to start my own distribution company in England, Lagoon Associates, modeled after Don Rugoff's Cinema 5 and pre-Miramax, films that could bridge art and commercial and where the campaigns had to be inspired to maximize their potential.

I've always held that a good film could be saved by an inventive campaign if the film wasn't performing. The advertising components (trailer, TV and radio spots) but especially the key art could make the difference in that era if ingeniously presented.

While The Terminal Man campaign was blossoming, the film I was launching the company with was Barbet Schroeder's La Valee, a mesmerizing, largely non-verbal journey to the unknown interior of Papua New Guinea, said to be paradise. Bulle Ogier starred as the bourgeois Parisian who becomes more committed to the search than the hippies she joins on the journey. I re-titled it in English to The Valley (Obscured by Clouds), the subtitle being the name of the Pink Floyd soundtrack album.

Then, A Bigger Splash, Jack Hazan's film about master artist David Hockney and his circle of trendsetters, became available and like The Valley, was unlike anything else that had been seen before. The Cannes entry centered on the creation of a major painting during the breakup of a love affair.

Both films reflected aspects of the zeitgeist, opened within a month of each other and scored with audiences. The Valley eventually set a record for the number of playdates in England for a sub-titled film. Splash was the first arthouse film to open day and date in three separate London cinemas, establishing house records in each and running for a year in one.

Lagoon was off to a solid start. I began negotiating with Warner Bros. to release The Terminal Man. Kubrick said I had to do it. The campaign began to take shape.

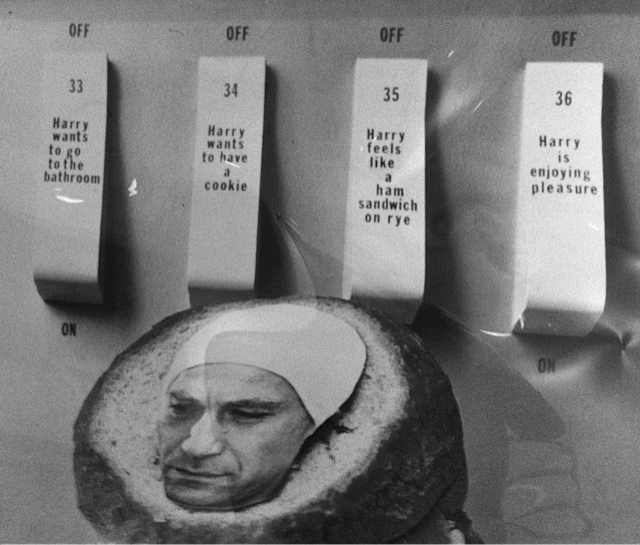

One of the film's most memorable scenes is Segal's post-operative examination where his senses are tested after the computer has been implanted in his brain.

Four medical buttons were shown at the top of the poster, each reflecting a different response and providing suggestive copy positioned within the key art, not the standard slogan placement.

"Harry wants to go the bathroom."

"Harry wants to have a cookie."

"Harry feels like a ham sandwich on rye."

"Harry is enjoying pleasure."

The central focus was a bandaged George Segal atop a collage of those images held together by scissor blades, another prominent image from the film. An impulse driven title treatment was designed by Philip Castle. Mike Hodges loved the concept.

While negotiations were continuing and Lagoon was enjoying trade attention from a tradition bound exhibition system, it became apparent that while The Terminal Man had unique production values and a major star, it was going to require more financial commitment than the Valley or Splash. Those films had innately provocative themes, with sexual sequences that grabbed the media and enticed the public. The Terminal Man was a dire admonition of scientific tinkering that left one numb. Exhibitors offered limited playdates and were wary. Editorial support was uncertain.

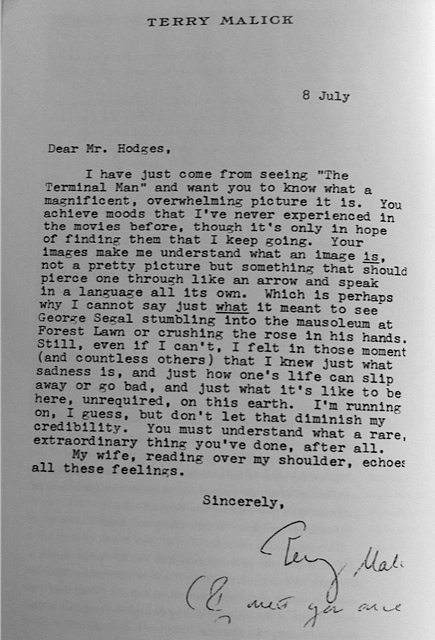

But then an unexpected validation appeared that confirmed everything I felt about The Terminal Man. Mike Hodges received a letter of overwhelming appreciation from Terrence Malick, who had recently been acclaimed as a major director for his debut film, Badlands. Malick wrote that seeing the film had restored his reason for making movies. He told Hodges, "Your images make me understand what an image is."

This was a rare testimonial from one important filmmaker to another. Anyone interested in serious filmmaking had to be compelled to see The Terminal Man after reading Malick's heartfelt assessment. It had to be a key component of the campaign. An ad was designed with the letter placed beneath a banner that read "Peer Talk."

Confident that the right campaign was now in place, I was hoping that negotiations with Wraner Bros. would be finalized.

( To be continued...with Robert Altman's arrival.)

All photos by Keith Hamshere, courtesy of Will & Co.