Part Two

It was the spring of 1975 and Robert Altman arrived in London with a print of Nashville. Word had already spread that this was an Altman milestone via Pauline Kael's glowing "preview" review in the New Yorker of his three hour-cut. The audience was filled with the major players of the British film community.

Bob was a recent colleague. We had our first encounter with Brewster McCloud at MGM. Bob was making McCabe & Mrs. Miller in Canada so we never met in person but he knew of my intense support for his film. When he came through London the previous year on his way to Cannes with Thieves Like Us, I went with Malcolm McDowell to a dinner party he and his wife, Kathryn, hosted, and we became fast friends.

After the Nashville screening, he invited me to a private reception in his suite at Claridges, which lasted into the wee hours. Through a smoke-filled haze, I remembered the next morning he had asked me to act in his next film, Buffalo Bill and the Indians. It was due to start shooting in Calgary in the fall. I was stunned and didn't know what to do.

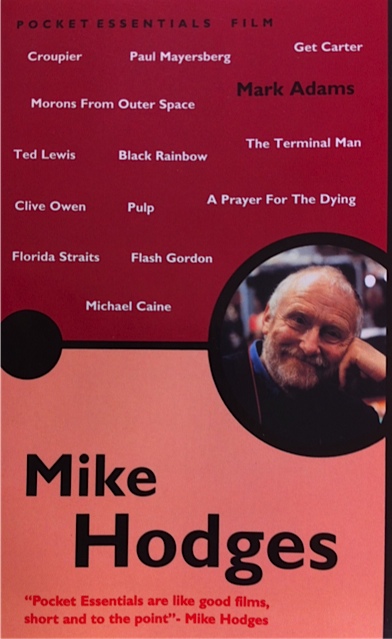

Malcolm and I had plans for several features; Lagoon was essentially my one-man baby, operating with just one assistant, and The Terminal Man was looming. Both Malcolm and Mike Hodges said it was an opportunity and an experience I shouldn't miss and I'd be back in the beginning of the new year.

Long story short, making Buffalo Bill was the most exhilarating, exciting, fun time I'd ever had. Bob had a secondary plan as well, having me handle the film's publicity along with acting as the accountant for the wild west show. It was a classic Altman two-for-one budgetary benefit -- which then committed me to the film's release and began a long-term creative relationship.

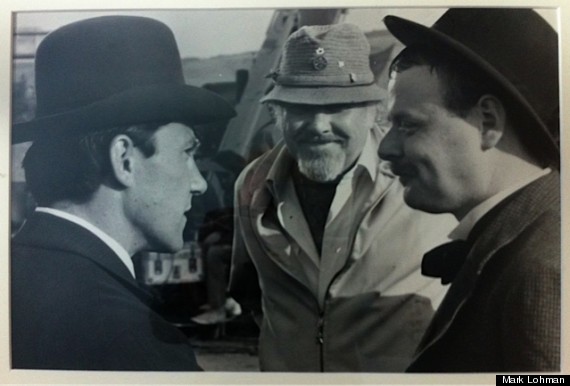

Harvey Keitel, Robert Altman and the author, Mike Kaplan, on the set of Buffalo Bill and the Indians, 1975.

For the next five years, I managed to keep Lagoon going through long distance communication from Los Angeles and a few months each year in London. The Terminal Man was too daunting a challenge to undertake without a continuous, hands-on London stay. And then, the main ancillary possibility -- the U.K. television rights -- were sold. I couldn't undertake a theatrical release without television. It was prohibitive.

Altman had moved to Europe after the release of Popeye (1980); Hodges had made Flash Gordon and Black Rainbow; I had produced The Whales of August and kept my hand in marketing, and in 1992 The Terminal Man surfaced again -- unexpectedly or synchronously.

I had rejoined forces with Altman for the U.S. release of Vincent & Theo and began a two-year quest to find the financing for his mosaic of Raymond Carver's short stories, which would become Short Cuts.

We spoke multiple times daily as financing was proving difficult -- nothing new. Then Bob was given the chance to offer his satiric take on Hollywood in The Player. As I was around the set daily discussing each potential development for Short Cuts, I was recruited for a role in The Player, playing the studio marketing head.

I'd also become an avid collector of vintage movie posters so we'd consult on where to get specific posters he wanted for the film -- largely B movie titles that people wouldn't recognize -- Joseph Losey's remake of M; several Robert Cummings comedies -- and the occasional major title for a key placement in a scene, the stunning one-sheet forRed Headed Woman, Jean Harlow's breakthrough role.

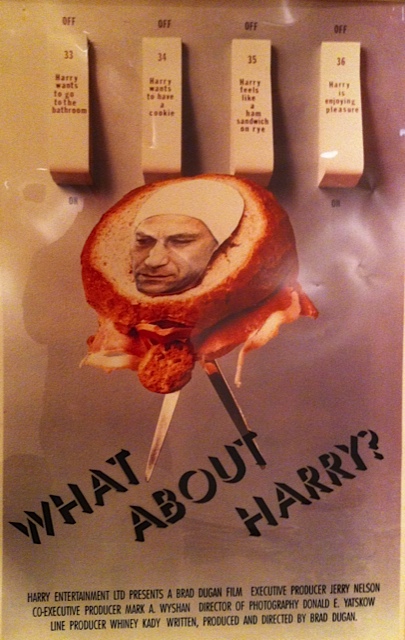

And then he wanted a poster to represent an unreleased studio film for a scene set in a meeting with production head Tim Robbins. It had to be one that a studio would commission and had to look believable... The Terminal Man design.

I explained its history to Bob, which he fully appreciated. He thought the concept was timeless when I brought it from storage. He was an admirer of Hodges's films; had worked with George Segal in California Split and I'm convinced he had to subliminally recognize a similarity in the collage to the leggy peace sign logo used as the key art for M*A*S*H.

Bob looked at the "Harry" responses on the button controls and said, "We'll change the title and make up some credits. Call it What About Harry?"

The poster can be seen in The Player, centrally positioned in the scene.

I called Mike to tell him at least part of The Terminal Man had surfaced.

It would take another 10 years for the film to reappear as a result of the recognition Hodges received with the unexpected emergence of Croupier (1998), his hypnotic film noir character study that brought Clive Owen to move stardom.

Mike sent a copy shortly before it was to open in England in a one-week engagement at the National Film Theatre in London, a peripheral booking without benefit of a trailer, poster or marketing budget. Its fate was continuing the mishandling of Hodges' work; Croupier had been passed over by every distributor and film festival and was destined for video oblivion.

Like all of his movies, its central character is a complex loner, this time a novelist turning to the gambling world for survival and then becoming addicted "to watching people lose." It was a gripping thriller with Owen giving a mesmerizing performance. He was an intellectual James Bond.

I was astonished that this very accessible movie was being abandoned. Though it had made the rounds and been rejected, I was determined to make something happen. A deal was struck with Film Four for me to act as sales agent (my first) and for the next two years, I became Croupier's godfather, eventually securing U.S. distribution, collaborating on the marketing and watching it become the most successful independent film of its year. The U.S. critical and popular success even scored a solid re-release in England.

The first reaction came at Croupier's American unveiling at the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles. Programming head Dennis Bartok planned a special showing along with a partial Hodges retrospective. The Terminal Man was an essential component but Warner Bros. did not have a decent print.

Kubrick was the only person who could solve the problem by asking the studio to strike a new one. He'd continue to admire Hodges' work and was responsible for Hodges' directing the English-language version of Fellini's And the Ship Sails On when the Italian maestro called Kubrick asking whom he would recommend.

In a few days, word arrived that a new print of The Terminal Man would be available for the Cinematheque showing.

Croupier's success was secured when Andrew Sarris wrote in his review that Hodges was "one of the most underappreciated and virtually unknown masters of the medium over the last 30 years." That quote keyed the campaign as the rave reviews came in and the public responded. Further, it paved the way for a reassessment of Hodges' work at retrospectives throughout the world, from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to the The National Film Theatre in London. The Terminal Man was always programmed, receiving new appreciation.

In 2003, Paramount Classics agreed to distribute and co-finance Hodges' next film, I'll Sleep When I'm Dead, a drama that subverted film noir traditions. One thought after Croupier that a second Mike Hodges-Clive Owen movie would be easy to finance but it took two years. Even after a success, one always begins at square one.

Festivals now asked for Hodges' latest "autopsy of society." This produced further retrospective exposure for The Terminal Man, the first at the 2003 Edinburgh Film Festival, where I'll Sleep premiered. And after 29 years, The Terminal Man was presented without that first expository scene which studio notes had insisted would give the audience "someone to root for." That first showing of "the director's cut," which Hodges edited himself by removing the self-contained opening scene, also marked the film's first theatrical showing in Great Britain since the 1974 London Film Festival.

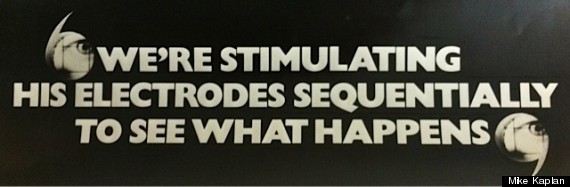

Edinburgh was also the first time I'd heard "dystopian" used to describe the film. The word had come into fashion but I needed a dictionary to learn that dystopian meant 'a culture where people lead dehumanized lives or are unhappy because they are not treated fairly.'

It was accurate to a point but dystopian doesn't account for Hodges's ironic humor or the emotional sophistication of Segal's performance, which audiences were unprepared for in 1974, when Segal was the leading romantic comedy actor of the time.

Dystopian, however, is now an accurate entry into the film which today's audiences understand. It also reflects the first frame of "the director's cut," which grabs you with an immediate feeling of unease as you are forced to focus on an eye looking through a peephole surrounded by a sea of black as voices of hospital orderlies comment on their patients... or us.

In his incisive essay on Hodges in The Guardian --"The Return of the Outsider" --Gavin Lambert, the noted critic, novelist, biographer and Oscar-nominated screenwriter (The Slide Area, Sons and Lovers, Inside Daisy Clover) called The Terminal Man the first of Hodges' masterworks, with "It's the most bitter of all Hodges' ironic endings, as Benson had always feared the potential of science to manipulate human life."

Lambert had also worked for a time with Kubrick as a reader and production advisor.

He called after viewing The Terminal Man and when we finished gong over some facts, he offered, confidently, "I bet Stanley loved this film."

On Friday, March 29, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art's Bing Theatre, Hodges's director's cut of The Terminal Man will be shown for the first time in America as part of LACMA'S "Sci-Fi After Kubrick" series.

It's a rare opportunity to discover a major movie, but I suggest you park a good distance from the theater to give yourself enough time for a decent walk afterwards. You'll need to unwind from a bracing experience.

All photos by Keith Hamshere, courtesy of Will & Co.

To read Part One, click here.