How has financialization changed the real economy?

James and Simon do an excellent job tracing the history of the conflict between the financial sector and the government in their book "13 Bankers." They do this history in two dimensions: first as a history of the United States' complicated relationship with the financial sector and large, concentrated banks, and second as a cross-section of the world in the late 1990s and early 21st century. From Andrew Jackson to recent problems in South Korea, they tell a narrative that connects ways in which the financial sector, when too big and too connected, is capable of capturing their regulators.

One thing that worries financial reformers is that we are rebuilding the financial sector of 2005-2007 with some additional legal powers for regulators to use in the middle of a crisis. Simon has written convincingly that failure to break this cycle will constitute a "doom loop", which explains that the next crisis will be even worse.

I want to think of this question in a different way - what is the impact on the real economy of keeping this financial sector going? I want to lay out four broad points to begin discussion as we enter into the potential recovery with a new permanent state of worry of financial crises.

Distribution

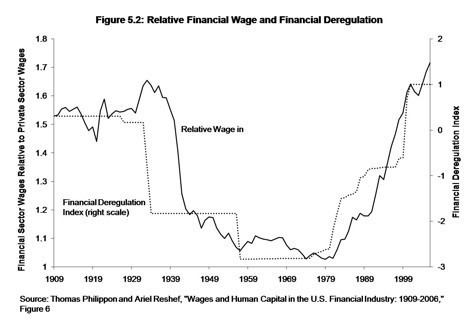

Inequality has skyrocketed in the United States over the past 30 years. And as we can see above, 30 years of massive growth in the compensation of the financial sector has tracked deregulation. It is also worth noting that this is a time period in which most of the gains from increases in productivity have been captured by the top 1% of Americans:

This sets up my first question: In what ways do we see financialization increasing the inequality of a society? If those gains to that 1% are predicated on complexity as a form of rent-seeking, or of high leverage ratios with the upside privatized and the tail risk losses socialized, this changes the narrative for much of the rationalization of this massive increase in inequality.

The follow up question is far harder: in what ways do we see the full concentration of power in the financial sector leading to stagnating wages? Is there a relationship here, and how best to investigate it? Does this power differential put labor in a weaker bargaining position? Does it distort the priorities and expectations of managers and CEOs? This question will need more exploration.

A New Labor Contract

Think of the work experience of a Wall Street analyst. (Here the ethnography work of Karen Ho, particularly her book Liquidated, is useful.) It's a form of labor with a strictly quantitatively graded measurement system, "rank-and-yank" style of rapid promotions, and massive turnover and layoffs. This rampant job insecurity is made coherent through strict market identification, with a special emphasis on working for power, prestige and most of all, cash. It's a job where being "smart" and "working hard" are the primary values that override any other concerns. It is fiercely hierarchical, centered around a pernicious form of meritocratic elitism. The "superstar" contract generates inequality, uncertainty and anxiety but also ruthless internal competition and an adversarial relationship with clients and co-workers.

And it is a labor experience that is being propagated into the real economy. Ho's point is that this employment habitus structures how these analysts both study, but also then create, expectations of the corporate and real economy. So as the financial sector advises the real economy through a network of consultancy and analysts, it projects its own labor experiences onto its subjects. This experience of labor colonization brings a superstar work ethic to places it did not formerly exist, and emphasizes cash as the primary goal of work instead of the myriad of dense virtues that come with a job well done.

The question of whether or not this is happening, and the mechanisms under which it is happening, will need to be explored going forward.

The Rage of the 1.5% Class

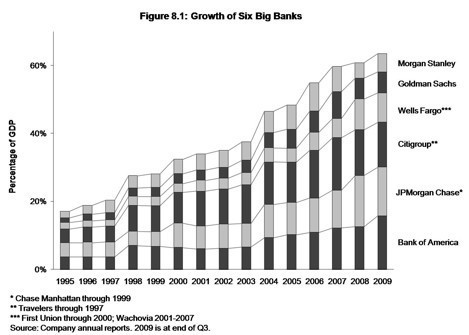

By ring-fencing the top 6 firms, protecting their business lines but without forcing them to make any substantial changes, the government intervention may have increased the concentration of the financial sector.

The medium financial players are the natural check on the power of the biggest financial players.

I saw something a while back that made me pause. Wall Street Journal, Proxy Plan Roils Talks on Finance Rules:

But in the bill launched this week by Senate Democrats, a little-noticed provision designed to give shareholders more clout is emerging as a stumbling block....The move encountered resistance from business groups...now, the Chamber is mobilizing forces to lobby lawmakers to kill the provision...Kurt Schacht, managing director at CFA Institute, an association for investment professionals that supports the idea, said, "The important test for lawmakers will be whether they can hold the line for these important investor protections. We expect that banking and other special interests will do their level best to strip many of these important protections from the final bill."

My first instinct was "Why are the financial lobbyists fighting with the CFA Institute? Aren't they all on the same team?"

Do you know what a CFA is? It stands for "Certified Financial Analyst." According to here the median compensation for a CFA is $180,000, and CFAs with 10 years of experience or more have reported median compensation of $248,000. At a salary (assuming that's the household income) around $250,000 this puts them right around the top 1.5% of Americans, with 98.5% of Americans earning below them.

However we've just come from an era where all the real earnings growth has gone to the top 1%. So this got me thinking: why is the CFA fighting with the Chamber of Commerce? Don't their interests line up well? And then it hit me - Chamber of Commerce, the Financial Services Roundtable, the fsforum, they are all representing interests that clock in a notch above the top 1.5%. They are gunning to represent the interests of the top 1% in this current financial reform debate. And the CFAs could lose these fights.

What else? The CFA Institutional Centre for Financial Market Integrity sponsored a study of derivatives regulation, U.S. Financial Regulatory Reform: The Investors' Perspective, a blue-ribbon panel of financial reforms, that suggested: "Standardized derivatives should trade on regulated exchanges and clear centrally, OTC trading in derivatives should be strictly limited and subject to robust federal regulation...The United States should lead a global effort to strengthen and harmonize derivatives regulation." A derivatives battle is being fought tooth-and-nail over these very reforms.

What else? The CFA did a poll of about the Volcker Rule:

And a remarkable 68% of respondents approve or strongly approve of the Volcker Rule. Only 20% of the elite 1.5% of our population oppose the Volcker Rule; however, when you have all the power and influence only going to the top 0.1% who oppose all these reforms, it's not particularly easy to be represented. This is what political disenfranchisement coming from economic inequality looks like.

A New Elite

There's a lot of talk about brain drain as a result of finance. Our smartest minds are dedicating their lives to finding ways to trade ahead of our pensions and 401(k)s 15 milliseconds in order to make a windfall, instead of leading the globe on any number of much more worthwhile endeavors. This is a major problem. Simon Johnson is a professor of entrepreneurship at the Sloan School of Management at MIT and must see this unfortunate trend firsthand. I would love to hear more from him on this matter.

But I'd like to go further and note that increasingly our elites, be it government, corporate, etc., will come from the financial sector. Notice Ezra Klein's interview with a Harvard student who works on Wall Street. For him, it's something to do for a few years before moving on to elite positions in other parts of the economy.

But what kind of future elites will the next decades feature when their primary experience of work and the economy will be fashioned through work in the financial market? Obviously, the superstar economy and "rip their face off" client relationship undermines any potential for solidarity. But it also undermines entrepreneurship, even though it is surrounded by business. When a business is something to manage from the aerial view of a spreadsheet, when it is something to breakup or build up solely for the purpose of manipulating a stock price in the short term, it isn't part of the organic process of finding a way of advancing the economy through meeting the needs of consumers and a work force.

A disadvantage to this crisis, as opposed to the 1970s Keynesian crash, was that it occurred so fast that it became another policy issue instead of a call to rethink the way our real economy is put together. With the clock already running on next major financial collapse, I hope there will be time to take a step back and realize that the problems here aren't some rich people ripping off other rich people, but that this new financial power is shaping the world and the experiences of millions of people who aren't directly on Wall Street.