A Conversation With Steve Earle

Mike Ragogna: Steve, your novel I'll Never Get Out Of This World Alive, imagines the troubled life of Doc Ebersole as he is haunted by the ghost of his former patient and friend, Hank Williams. What inspired you to write something like this?

Steve Earle: I had always heard there was a doctor traveling with Hank; turns out the guy wasn't really a doctor, he was a quack. I decided the idea that he was a doctor was more interesting, and I came up with my own character, Doc Ebersole. It started out as a simple ghost story and became a Harry Potter book for adults by the end, it got kind out of hand, but I'm pretty proud of it actually.

MR: And it has the same title as your latest album.

SE: The book was always going to be called, I'll Never Get Out Of This World Alive because it was the last single that Hank Williams released before his death and it went to #1 after he died. Kind of weird it worked out that way, but it did. I'd been working on my record and the book was finished, turned in, and getting ready to be published. My producer and I were finished recording, mixing, and in the process of sequencing. It occurred to me that the songs were about a lot of the same things that the book was about--mortality, not in the morbid western sense, mortality in the sense of something we all have to deal with, in a spiritual sense. I lost my dad a few years ago, and when the generation before you goes, you're next. It was something, as an artist, I found myself dealing with and writing about a lot. I made the record and the book in pretty much the same time frame. I decided to give them the same title and capitalize on the confusion.

MR: So the record is dealing with a lot of the same issues that the book talks about, but it's not a companion piece to the book.

SE: Correct, you won't hear Doc Ebersol singing on the album.

MR: Although "Waiting On The Sky," to me, could be the crossover piece. It sets up the album with concepts of mortality, just as you mentioned. Otherwise, it seems very personal.

SE: This record is probably the most personal of any record I've ever made. I couldn't figure out what it was about until the end. The book was inevitably taking up a lot of space in my consciousness and I made the connection. I worked on it for a long time; finally finishing it was a big deal to me.

MR: I have to say, your version of your original "I Am A Wanderer" resonates with me deeply. You said this album dealt with issues that are more personal than not. What was behind this song?

SE: I wrote "I Am A Wanderer" and "God Is God" originally for Joan Baez's last record, but it's still me talking when I'm writing for someone else, at least to some extent. "I Am A Wanderer" is about the things that Joan and I have in common, that we might as well do something while we're here. How everything we do and say matters. It affects other people in the world, not just the people that we see. Basically, try not to forget about anybody.

MR: You and Joan have gotten close over the years, haven't you.

SE: Yeah, it's a big deal for a songwriter of my generation and political depth to have Joan Baez sing six of your songs. It's hard for me to believe but it's true.

MR: To me, it seems you had a major turning point or personal growth spurt with your Jerusalem album.

SE: Well, Copperhead Road is a pretty political album and song. It was my post Vietnam record. It was being made the same time as Platoon and [Springsteen's] Born In The USA. There was a period in the '80s when we were all finally dealing with the war. Jerusalem was the first time I ever intentionally set out to make a record that was overtly political. I don't think I'm a political songwriter, but I made two political records in a row because there was nothing else to do for a writer like me. Jerusalem is my post 9/11 record. The Revolution Starts Now is me reacting to living through a decade of war. It's happened twice in my lifetime. The fact of the matter is we've constantly been at war in my lifetime. Pete Seeger says all songs are political, even lullabies are political to babies.

MR: Steve, you've been doing readings of I'll Never Get Out Of This World Alive since its release?

SE: Right, I did quite a few when the book first came out, and it's currently being released in paperback.

MR: What's your favorite part to read?

SE: Pretty early in the book, when Doc Ebersol first sets up for business. The paragraphs that describe his beer joint where he has a table in the back that serves as his office that he uses to consult potential customers. His main livelihood is that he performs abortions. It shows how hard Doc has fallen. He was, at one time, a physician from a respected family in New Orleans. He ended up in San Antonio because of his own weaknesses.

MR: What bonded him and Hank Williams?

SE: The real Doc Ebersol was a man named Toby Marshall who claimed he could cure alcoholism with chlorhydrate, which is a barbiturate. It cured him alright; you can't drink if your dead. Hank had a lot of alcohol, a lot of chlorhydrate, and a fair amount of morphine in his system when he died. He took morphine because he was in excruciating pain for most of his life from spina bifida.

MR: Would Hank Williams have been drawn to someone like that?

SE: Hank Williams was an alcoholic, he had people in his life that weren't good to hang out with, so probably yes.

MR: I see you will be doing a reading at Iowa City's Live From the Prairie Lights at 4pm on August 7th followed by a Q&A.

SE: Yeah, I'll read a little from the book, answer some questions, and sound check for my show.

MR: Which will be at Iowa City's Englert Theatre at 8pm.

SE: Yeah.

MR: What are the most common questions people have about the book?

SE: People often ask me how writing books compares with writing songs. I tell them books take longer.

MR: What is your advice for new artists?

SE: I think you have to wake up in the morning and remember that you've committed to doing something that not everybody gets to do. If you get to make any sort of living doing and kind of art, then you are very fortunate. I've spent a lot of years doing this and I was in my thirties before I made any money. It can take a long time, hang in there.

MR: Thanks, Steve. All the best.

SE: Thanks, Mike.

Transcribed by Theo Whitley

A Conversation With Ravi Coltrane

Mike Ragogna: Ravi, let's get into the concept of your new album, Spirit Fiction.

Ravi Coltrane: I wouldn't call it a play on words, but I do like to let the listener decide what the meaning of those words may suggest to them. It's a little abstract, but not too abstract.

MR: You're the son of jazz icons, Alice and John Coltrane, and in the song "Marilyn & Tammy," you're talking about your other relatives.

RC: That song in particular, yes. It's dedicated to my mother's sister, Marilyn McLeod and her daughter Tamra Ellison. They were best friends in all of their time together; Tammy passed away, sadly, a few years ago. There's something about this tune that reminds of their vibe and their energy together.

MR: Speaking of energy, how do you get inspired?

RC: I'm inspired by the challenge of it, the unknown. It's always been very exciting for me, when things have been mastered before to recreate the past in a way that's more traditional. That doesn't always excite me that much.

MR: You had Joe Lavano with you on this project overseeing as producer. You also had two variations on the "bands" you used. Can you go into how you approached this album creatively?

RC: I had a lot of ideas, a lot of ambition, and sometimes, not all of it works. You might try a thousand different things and only find five that you think are worthwhile. I always overplan a little bit when I do these recordings. I try to record more material than I know will even fit on the album, just to give me the option to arrange things after the fact. Joe Lavano was a guy I have been hanging out with since the late '80s. He's a mentor, a great friend, and obviously, one of our greatest saxophonists out here. I've been working with him more closely over the last five years or so in the group saxophone summit along with David Liebman. I'm liking his style in the studio; I made a few record dates with him just to watch him do his thing in the studio--very clean, very efficient, and a little bit of that old school edge. I thought that would be a good thing for me to incorporate into my sessions. I had performed a little bit with my regular band in a few sessions last year, and I knew I was going to record some more. I had this idea of reforming an older group that's featured on my second record, From The Round Box, which is a quintet. It was an interesting turn of fate having these sessions with two different groups and have the music work together and balance out.

MR: You're a great improviser, of course, and I want to ask you about the song "Roads Cross." It's one of the great improv moments on the album, and it starts off the album, setting the mood. Can you talk about how it was created?

RC: Sure, thank you for commenting on that, that's the whole idea with "Roads Cross." It's an introduction for the album. The album, for all intents and purposes, starts with the next track, "Clepto." "Roads Cross" is saying, "Here we are, this is what we're about, we're going to dig as deep as we can in regards to improvisation and focused listening, like a kind of unified collective of improvisers." For me, that piece, "Roads Cross," and the other take of it, which is called "Cross Roads," really illustrate where I feel we're coming from as improvisers. We like to do spontaneous improvs during the course of a day in the studio. We have some planned materials, some tunes and whatnot. Then we'll throw some ideas in, we'll take a break and say, "Hey let's try an improv where half the bands does this and the other half does that. Roll the tape, let's go!" That's essentially how it was. A bunch of them don't work, then you have one or two that really do. I think they were some of the strongest pieces we recorded.

MR: I also want to bring up another experiment you had on the project. You tell me if its improv or not. On "Spring & Hudson"--as in the NYC streets--it's just you and E.J., the drummer. You recorded it in such a way as to emulate The Half Note.

RC: Yeah, I was literally facing my drummer E.J. Strickland. We set up some stereo microphones in front of the saxophone and I was moving as if I were on a stage with him. I had a little more flexibility in that regard. I love playing duets with people. If we're playing on a stage, my back is to the musicians. When you can face a musician directly on, you can start picking up on visual cues; you can see him lift his stick up, you can see when he is going to hit the drum; you can start to mirror the energy of their physical movements. It affects the improvisations when both musicians are looking dead at each other. The title does come from the quote "The Half Note." The bandstand was so small that the musicians were forced to set up right next to each other facing each other. You can hear how that proximity affects the way they improvise and how well they can anticipate each other's moves.

MR: There's something romanticized about playing those smaller clubs where you have challenges performance-wise. How do you feel about that, looking at it after all these years?

RC: It affected the work. I don't know if music would have progressed and grown the way it did if it wasn't cultivated and developed in small clubs. To play this music on a giant stage in front of a giant audience is a totally different thing. When you're in a tight room where you can literally hear every note at every moment, every beat at every pulse, you can get a certain type of precision, a certain kind of exactness to your feel and your phrasing to how the music flows. It's hard to imagine this music developing the way it did in any other type of environment.

MR: After a club date, you theoretically go home and you sleep, then you wake up. Then after a dream, you come up with a title for one of your songs, which is called "Change My Girl," right?

RC: We usually don't sleep after the club dates, the sun's usually coming up and we have to get ready for the next day's work.

MR: (laughs) I was just setting the question up, but let's get into the song's title coming to you in a dream.

RC: I like to keep a list of titles and things. You might be walking down the street and a phrase might come to your head. You say, "That could make a good title," so I just write them down. That was from a dream that I had years and years and years ago. A bunch of us were at a session and trying to decide what tune to play next. Somebody was saying, "What about this, what about this," then someone said, "What about 'Change My Girl?' In the dream, I said, "Okay, fine, let's play that, everyone knows that tune." It seemed so casual in the dream, as if it were a standard that everybody knew. So I woke up, wrote it down, and here we are decades later.

MR: And that's obviously also how you got the title "Who Wants Ice Cream?"

RC: (laughs) For me, it's "Who Doesn't Want Ice Cream?" It's redundant. That's a Ralph Alessi song. He is a great composer and also a master at coming up with these very idiosyncratic titles. It's a fun song with a fun title. I think people like the title as much as the song. It's a win-win situation.

MR: You have three numbers by him on this project.

RC: Yes, he composed three pieces, and he is featured on a few others.

MR: You also cover "Check Out Time."

RC: That's right, Ornette Coleman is one of our biggest leaders. We've been following his music for as long as we've been on this planet. I have recorded his music before, and always feel compelled to play his music. Again, he is one of our great heroes. To be in a recording session with Joe Lavano and Geri Allen and not go into an Ornette Coleman song is not the right thing to do. He did two records on Blue Notes. One was called New York Is Now, the other is Love Call.

MR: You also do a Paul Motion song called "Fantasm."

RC: Yes we do, "Fantasm" is a beautiful composition. Paul had just passed away maybe about a month or so before that session. Joe's relationship with Paul dates back to late '70s, '80s. I think he was in his twenties when he met Paul for the first time. I asked Joe if there was a song that he thought would be appropriate to do. He said right away, "Fantasm." I felt like it was something that needed to happen in that moment.

MR: Ravi, what advice do you have for new artists?

RC: Keep an open mind. Music lives not only in the present, it can also live in the future. People have this idea that jazz lives only in the past. Obviously, we have great monuments and great pillars from the past that will always guide us and inform us. But really, they were trying to make sense towards the future. I don't think you can listen to Thelonius Monk without realizing that it's really what's happening. His command and knowledge of tradition and what came before him is firm. But really, his desire to move forward and express a more personal vision in music, that's when innovation happens. We're not often taught as young music students to use our intuition and imagination. We're taught to emulate and copy the past. A lot of us get very comfortable doing that and feel no desire to rely more on our intuitions. Following our path to "what if" is much harder to teach or instill in a young person. For me, there are great benefits with trying to embrace that. All you have to do is look at the past; that's what these guys did. The John Coltranes, the Miles Davis', the Charlie Parkers took on the past but embraced the future even more so.

MR: Beautiful answer, Ravi. I have a question from David Proctor Hurlin, an amazing jazz drummer here in the Midwest. He asks you, "In the context of improvisation, how does one balance accountability to musical form and structure, and accountability to total desire."

RC: Accountability...I'm trying to understand how he's relating that to improvisation.

MR: Maybe the actual performance to the musical form and structure?

RC: What are our goals as improvisers? To play something we've worked out in advance, or actually play something that is totally caused by the moment, that's played for the moment, for the purposes of the moment. Identifying what our roles truly are as jazz musicians, that's key, really. Some people are like, "I just want to swing, I just want to carry the flag for the tradition." That's a moot level, that's first gear. It's a necessity that is a natural component, but it's what comes after that. As far as accountability goes, we have to do more than master the past. We have to embrace something more personal, and hope that it will lead to something new.

MR: Do you ever feel your parents John and Alice smiling down on you?

RC: I hope so, I hope they're smiling.

MR: When you create music, do thoughts of them ever come to you?

RC: They are in my thoughts all the time. They are a part of everything I do. Not in a romanticized kind of way. I can't even articulate it. It's just there.

Tracks:

1. Roads Cross

2. Klepto

3. Spirit Fiction

4. The Change, My Girl

5. Who Wants Ice Cream

6. Spring & Hudson

7. Cross Roads

8. Yellow Cat

9. Check Out Time

10. Fantasm

11. Marilyn & Tammy

Transcribed by Theo Whitley

A Conversation With Jerry Douglas

Mike Ragogna: Jerry Douglas, thanks for talking us on the only solar-powered radio station in the Midwest, KRUU-FM. Bam.

Jerry Douglas: I played at the Telluride bluegrass every year and they buy all their power from a solar-powered station. They run their whole festival on solar power.

MR: Excellent. Is that the only one that's out there?

JD: That's the only one I know of.

MR: I know a couple of groups who try to use only solar power when they're on the road.

JD: It's still new enough that people aren't really hip to how you would pull that off--getting in touch with who's selling solar power, and that kind of thing. But I think it's a great idea and we all want to get away from fossil fuel.

MR: It would be great to get to more alternative energies as soon as possible, especially since no one can afford fossil fuels any more.

JD: We need to, we can go to the sun and get more.

MR: Yeah, and watch gas prices spike right before the election. Anyway, Jerry, let's get into your album Traveler. You've released quite few albums since 1979, that you've been on but you've also played on at least 1,500-1,600 albums by others also. What do you think about that?

JD: Well, I hope I have nothing else to prove. I don't know what the number is but at this point it's probably somewhere around 2,000, but I don't count that kind of stuff. Other people keep bringing up numbers and I say if you think that's the number, by now, it's bigger.

MR: Why, just after last week, the number is bigger.

JD: Yeah, I played a Kate Rusby session here in my studio just two days ago. So there, add another one.

MR: (laughs) 2001: A Douglas Odyssey.

JD: (laughs) I don't know how many there are. It doesn't really matter to me. I'm sure I had fun on most of them.

MR: Or at least the artist had fun that you played on the project. But I bet you at least had fun on a little project titled O Brother Where Art Thou?

JD: Oh yeah, that was a blast!

MR: And you, sir were a Soggy Bottom Boy. What was that like?

JD: It was a different recording situation because we recorded that record the way they would have recorded in the '40s, which was three microphones scattered in a pattern. Instead of walking up to a microphone to play, you walked into an area. It was so that you could hear the choreography of how the record was recorded instead of just a mono recording, so you could hear people moving around.

MR: It's closer to the live situation in that way.

JD: Yeah, you can see it, it's more visual.

MR: Before we leave that subject, I want to ask you, of all of these recordings, you're on Elvis Costello albums like Secret, Profane and Sugarcane. And you go way back to the days of J.D. Crowe & The New South, when you recorded as part of that unit.

JD: Yeah, this is an anniversary of that record, but I think it was thirty years ago that we were an actual band. It had to be longer ago than that...that was 1975. I'm dating myself.

MR: Yeah, like a fine wine, Jerry. Okay, another project you worked on that I wanted to throw out there was Will The Circle Be Unbroken. You're on the second release of that trilogy as part of the band, right?

JD: Yeah, the second one. That was probably the closest thing to a real job I ever had. We clocked in every day for two weeks and would sit in our same chair with our same microphone, though we wouldn't bring a lunchbox or anything. Then they'd film it and we'd do it with all these different artists. It was really, really fun.

MR: Nice, I can imagine. Are you aware that you're considered to be the world's best dobro player?

JD: Well, I'll take it. I like some other dobro players that I listen to. Finally, there are some other dobro players. For years, there weren't any dobro players and it's grown a thousand-fold since I started playing. It's nice to hear other people playing the same instrument so I don't feel so alone.

MR: What got you into this lonely little instrument?

JD: I started playing dobro when I was eleven years old after hearing Uncle Josh Graves play with Les Flat and Earl Scruggs. He was just really such a soulful player. The instrument itself is a slide guitar, so it's really a highly emotive instrument and goes really well with vocals and he just got me. He just stabbed me right in the heart with the thing and I wanted to play. I was a guitar player at the time. I was playing my Silvertone guitar, which was like playing a cheese grater, it was so high and hurt my fingers. I first played slide on my guitar and learned the basics of dobro playing from that.

MR: It's really pretty wild just how many recordings and artists you backed up, one of which is Paul Simon. This slides us into your new album, Traveler. On that album, you have Mumford & Sons and Paul Simon on your cover of "The Boxer." What's that story?

JD: Mumford have been great friends of mine, sort of surrogate sons of mine, for four years now. I first met them at Telluride Bluegrass Festival out in Colorado. The promoter called me and asked if I'd heard of Mumford & Sons, and I said I had because my daughter and sons have turned me on to them. They keep me fresh and keep my listening to new music all the time. They'd heard of them and they played them for me and I loved them. He said, "I'm going to have them at the festival but they don't know anybody and I would love you to be the face of the festival for them, to play with them if you would." So I played with them for the first time there, and we've been great friends since then. I asked them if they would be on the record, if we could do a song on the record. They said yes. Marcus Mumford and I were talking. I was in London and he was out in the country somewhere and we were talking about what song to do and he said, "How about 'The Boxer.'" I said, "I don't know, Paul Simon might do 'The Boxer,'" so he said, "Oh, we wouldn't want to mess with that." But I started thinking and thought maybe we should do this, so I kept "The Boxer" with them. Out in the country, after my tour with Alison Krauss was over, I stayed around in England and went out in the country in England and had the boys come out. We recorded "The Boxer" there, brought it home, played it for Paul, and he loved it. He wanted to be on it...Paul Simon wanted to be on his own song with someone else singing lead and he singing harmony. I think he heard it a different way than he heard it before with somebody else singing it.

MR: Jerry, you have a couple of other interesting guests on this album including Eric Clapton on the track "Something You Got."

JD: I've known Eric for many years and we've talked about collaborating for a long time but the opportunity just didn't present itself. I've played on both of his Crossroads festivals with different people--with him, Vince Gill, and James Taylor on one, and with Alison and the band, we played on the second festival. I played a few songs with Eric and Sheryl Crow on the second festival. So when this record came around, I thought maybe I should try having a producer and I got Russ Titelman to produce the record. Russ is really a good producer, he's got a great track record, and has produced a few of Eric's records, one in particular was the Unplugged record, which had "Tears From Heaven." So it's a really great record he's produced. He's done James Taylor records, Paul Simon records, Steve Winwood records, a whole pile of records by Ry Cooder. But we talked about doing something forever. I'd never been in the position to have a producer. I'd always done it myself wearing both hats and it's a difficult thing to do. I never felt as if I'd play as well on my own records as I had on other people's records because I was too busy trying to do too many things.

MR: Let me ask you about "Frozen Fields" with guest Alison Krauss. You and she go way back. Can you give us a little history lesson?

JD: I first met Allison when she was fourteen years old. She had just signed with Rounder Records. Ken Irwin, who was one of the three people that founded Rounder Records, brought Alison down to Nashville and was looking for someone to produce her first record for them. He brought her over to Bela Fleck's house. Bela, Sam Bush and I were all there and I was just floored by what I heard. She was so much more interested in being a fiddle player at that point than a singer. We all said, "You're a singer. You need to take advantage of this great gift that you have." I ended up playing on the record, not producing the record, but playing on the whole record, and then producing the next record.

Since then, a lot of water's gone under the bridge, but that was when she was fourteen. Twenty-six years later, I'm in the band producing records with her. I've been in the band for fifteen years now. I went out on the road with her. She called me to see if I could come out and do the summer with the band and I said sure, I'd come out and help out, get them out of a jam. So, I went out and about two weeks into the tour, they asked me if I would just stay. I had a talk with my wife and we decided that since I was so burned out from playing in different sessions here in town, it was time to make a change. Fifteen years later, I'm still there.

This was a song that was originally cut for the newest Alison Krauss & Union Station record. The record's called "Paper Airplane" and it didn't go on the eleven-song record that was released by Rounder. It was one of my favorite songs that we cut for the record, so I snatched it up for my record.

MR: You must have more stories. Give us a couple of your favorite war stories.

JD: Oh man, there are so many. First, I've been on the road for so many years and in the studio. Since I've been with Alison, the guys in the band, Dan Tyminsky and Ron Block, they all have pretty different personalities. They are outgoing mostly, but Ron Block's a pretty quiet guy. One thing that I can think of that may be funny--not funny to Ron--is that we used to leave from the same place. When you travel on a bus, you have to all meet at one place and get on the bus. We'd meet at this supermarket, a Kroger, here, close to Nashville. We'd get on the bus, get a few things out of the store, and take off. Ron's a pretty quiet guy, so I think five times one summer, we left Ron at that Kroger because we just didn't notice that he wasn't on the bus until his phone would start ringing. We'd think, "Who's phone is that, whose phone is ringing?" And it was the only number he knew because all his phone numbers for us were stored in his phone. (laughs) He couldn't call us, but he did know his own number, and we'd finally find out that it was his phone and answer it. He'd be at the Kroger and sixty miles later we'd turn around and go get him. So be careful when you're on the road with a bunch of people. Always let them know where you're going.

MR: That sounds like too much fun, I don't know.

JD: (laughs) It became funny around the third time.

MR: Jerry, you're a Grammy winner thirteen times over. That's thirteen times. What do you have to say for yourself, young man?

JD: (laughs) Just the right place at the right time. They're all for different things, they're for different records, playing with Earl Scruggs on records, for producing different records. Grammys are a nice nod from your peers in the business, that there's some excellence in what you do which is very nice to hear. But we don't go out and make a record thinking this is a sure Grammy or something like that because nothing is for sure, not in that business. I make music to try to move people, to try to make their two hours that they're there to see me play better, get them away from whatever is bothering them, whatever happened to their week, their year, if they've lost somebody. There are all kinds of things, whatever is going on in their lives, when they are there to see me play, I want to change their lives. I want them to feel better about who they are, what's going on in their life. That's what music's about, it's about making you feel good, changing your life a little bit.

MR: Wow. Well, now you have the opportunity to change a few more lives by answering this next question. What advice do you have for new artists?

JD: New artists? It's tough out there. It's tougher than it's ever been, there are so many people out there trying to get record deals and plus there are so many ways to promote your music. The internet has opened up so many things that weren't available to me as a new artist. There are all kinds of ways to raise money online to get a jumpstart on a recording budget to allow you to buy some equipment to record. There all these new ways you can record at home, digital equipment that wasn't there when I started playing. The analog tape machine, which cost half a million dollars, was a little cost prohibitive. But now, the same quality studio that we were using, the same quality of recording, you can get for under $10,000. The equipment that we were working on was 2-3 million. You've got that, but you really need to have some belief in yourself, some real talent, and some other people. Surround yourself with who really believe in you and can help you in your endeavor. It's really important to have a good group of people behind you that can do part of it. You can't do everything yourself. That's what I would start out with. There's a lot more, but just watching some newer acts come up and fall by the wayside, some really talented people that shouldn't disappear, but do... The reasons that they do aren't because of them, but because they didn't have the help they need.

MR: That's really beautifully said. I dipped my toe into the management field for a while. Things didn't work out, but I got to see what was coming down the pike, the barrage of things that had to be juggled.

JD: It's a business, a cut-throat business, actually. I wouldn't say that to discourage anyone by any means. If you've got talent and you want people to hear you, the thing you can do to help yourself is to surround yourself with some really nice people, but play in front of as many people as you can, as often as you can.

MR: It's like trial by fire or better yet, molding the weapon in the fire.

JD: It is. You find out who you are while you're out there. You don't really know until you get out there. You can think you're the greatest thing in the world and you might find out that it's really not for you. But you might also come into your own while you're standing there.

MR: Speaking of playing, you've also gotten the Musician of the Year award three times from the CMA. Also, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded you the National Heritage Fellowship. You're named Artist in Residence for the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2008. The AMA...no, not the American Medical Association...

JD: (laughs)

MR: The Americana Music Association honored you with a lifetime achievement award just last year.

JD: I did an operation onstage.

MR: Must have been one awesome operation.

JD: I don't know, I just play the dobro and somebody's listening. Those things are great and they boost your confidence level, but they make you nervous as hell. They do all kinds of things to you. It's a mixed bag of feelings, but I've had a wonderful career and it's not anywhere over. I started really early and really young, but I've been really lucky to play with some really great people and tried to keep myself in good shape and walk the straight and narrow. There are just so many things about life that are the same as playing music, you know? You find some of the nicest people that play music because it's a language that crosses all barriers and you just try to be yourself. You don't try to be what you're not and sometimes, people give you something nice. It's a wonderful world if they do or if they don't, it's all fine. But I really appreciate all those things, the nice words you said and all of those things I've been given. I don't know what I would do to change anything, it's been a great life.

MR: Thanks for that. What about your touring, what does the future look like?

JD: Well, It's just our normal summer tour, a pretty relaxed schedule but working every week, all over the country. Then, actually, I'm going from Telluride to Brussels.

MR: That sounds like a song title.

JD: (laughs) We'll be with Allison in Europe, in Scandinavia. We'll be in Norway, Copenhagen, back in the UK...a pretty full summer. Then I'll start touring Traveler in the fall.

MR: It's really an honor speaking with you and I appreciate your time today. And I imagine before your tour, that number of projects your on 2,001 will probably be up to 2,500.

JD: I hope not, I don't know where I'll fit all that stuff in. I want to try to take it easy this summer as well. It's been a pleasure being here with you and I love the whole solar-powered idea, I think it's wonderful, and just wish everything ran on solar-power. It could, couldn't it?

MR: It absolutely could!

JD: We're working that way.

MR: Thanks, Jerry, and all the best in your future.

JD: Thanks for all your kind words.

Tracks:

1. On A Monday

2. Something You Got - with Eric Clapton

3. So Here We Are

4. The Boxer - with Mumford & Sons and Paul Simon

5. Duke and Cookie

6. High Blood Pressure - with Keb' Mo'

7. Gone To Fortingall

8. Right On Time - with Marc Cohn

9. American Tune / Spain

0. Frozen Fields - with Alison Krauss & Union Station

11. King Silkie

Transcribed by Narayana Windenberger

INTERMISSION: THE BOX STORY "WASTE THIS LIFE" (complete with trumpet part!)

A Conversation With P.O.D.'s Sonny Sandoval

Mike Ragogna: Uh-oh, Sonny Sandoval's on the phone.

Sonny Sandoval: Hey man!

MR: Sonny, your new album is titled Murdered Love. So just how murdered is this love?

SS: Oh my gosh, that's so heavy, huh? It's so heavy and deep. (laughs)

MR: Nah, I'm not sensing a lot of murdered love on here, although we need a little history on the song "Lost And Forever" just to be sure.

SS: "Lost And Forever"... When we finally decided to jump off our hiatus, the guys started fiddling around a little bit with some ideas. They came up with a groove and stuff. We got together and finished the song. We actually did a bunch of demo stuff. I just wrote the lyrics. It basically just has to do with my infatuation with the afterlife, always thinking about eternity and the eternal. Sometimes, you get caught up a little bit and you tend to lose your mind-set in it.

MR: We just joked about it, but on the title track, "Murdered Love," you are making a bigger than not statement, no?

SS: I'm a man of faith. It's a dark and eerie song. It's taking from the whole idea of crucifixion. The scriptures say the sky went black and the ground cracked open and the religious bell was split into two. It's kind of a desperate, almost hopeless moment--right on that moment, the death on the cross. I have my faith and I believe in Jesus, so it was more about what we did to love. God is love.

MR: And, to me, it also can be interpreted as what we sometimes do to relationships as well. Sonny, a somewhat relative song would be "Babylon The Murderer."

SS: Yeah, this album is real kind of Armageddon-ish, apocalyptic. But, if you're into reggae music, you associate Babylon with the world, world evils and corruptions. It's a common phrase in reggae music.

MR: Right. Sonny, let's talk about your background.

SS: I grew up in a crazy family. My grandmother and mother were from Italy, so I was raised Catholic. That kind of just meant going to church on Easter and Christmas. I saw a radical transformation in my family when they started going to a Christian church. I watched them fall in love with God. When I was 19 and my mom passed away from leukemia, it got me thinking about a lot of stuff. You know, I've always had a love and respect for God, but I didn't want a religion, I just wanted to walk hand-in-hand with God. For me, in my faith, it does that. There are so many faces of Christianity these days; sometimes people get lost. But it really just has to do with my relationship with Jesus.

MR: What moved your family from Catholicism to another kind of Christian following?

SS: Young family, drug dealing, crazy family, and to just watch the love of God penetrate their minds and hearts, one by one. It wasn't a religious thing, it was more of this experience when they were falling in love with the Lord. So the day my Mom died, I just said my own big boy prayer. I said I want to walk with you, I don't want religion, that's too confusing, I just want to walk with you and I've been on this journey for 20 years.

MR: And you took your relationship with God it into your music. How did you make that kind of a creative commitment?

SS: I had no dreams or aspirations of ever being a rock band. I liked the hardcore scene and my cousin was in the band and Marcos (Curiel) was in a different band, playing different keg parties and stuff. They had asked me to be in the band. You know, it's already crazy that I'm "Christian" and all of my friends think I'm crazy and to be the singer of this band is just as nuts, but it's a tool and an avenue to scream about my faith and my conversion. And we just started playing parties and took it a little serious and it was just part of the natural process of it.

MR: You realize with hits like "Alive" and "Youth Of A Nation," you've had a big effect on Christian youth in America. As that was happening, do think Christian parents were feeling, because of your material's messages, it was safer for their kids to go to your concerts over others?

SS: We were never Christian enough for the Christian community, and we were too Christian for the world, if that makes sense. We didn't market ourselves as a Christian band because I didn't know of such a thing. We just make music for people. I am grateful for the Christian community that has come support us over the past 20 years, but once we hit the mainstream, it was just that. Parents and kids have to decide what they listen to. We never tried to be the Christian superheroes or the spokesperson. Whether you're Christian or not, you would listen to the music and the lyrics and be moved by it. I feel they are. I feel this music is bigger than the four guys in the band.

MR: On the other hand, for sure, you've had an influence over a lot of Christian kids growing-up. And you were very popular with many Christian youth groups. How do you feel about having been an influence?

SS: I'm humbled. It's a humbling thing. If we can inspire and encourage somebody, whether they're a Christian or not, I take it as an honor. I'm so grateful for all of those kids who have been listening for years. Ultimately, I know it's God and whatever God's doing in their lives.

MR: Sonny, in addition to your hits, you had a fun excursion in a movie called Little Nicky starring a certain Adam Sandler. And the soundtrack featured P.O.D. recordings "Southtown," "Rock The Party" and "School Of Hard Knocks."

SS: One of the cool things about this rock industry is you never know who's listening. At that time, Adam Sandler, really loved our record. He was a P.O.D. fan. He wanted to throw our music in his movie and do the soundtrack. When you get awesome opportunities like that, it's cool, man. At the time, he was a big fan rock fan. There were a lot of fans from that genre--Incubus, Def Tones...a whole bunch of bands were in that process.

MR: Sonny, 9/11 was the release date for your Satellite album. Sure, there were other releases on that date, but looking back, what are your thoughts about that day, about thsat period of our nation's history?

SS: If anything, at that point, we couldn't care less about the band or the music, it had nothing to do with that. But, we were proud that "Alive" was already at the top of the video charts and on MTV, and it was a confirmation of the direction of the music, the hope, and the love that we put in the lyrics. It did mean something at that time. Out of all the music and bands that were played, we were one of three artists that were focused on. Our world was in a desperate place, and our world was looking for answers. At that time, nobody cared about sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll. Nobody cared about the Slipknots of the world; Lil' Wayne wasn't around then; nobody cared about the entertainment side. I was proud that we had a song called "Alive" on the top of the charts and it was about being grateful for every breath that you take.

MR: Looking back at your Satellite period and now looking at your new album Murdered Love, what do you feel are your personal and creative jumps that have occurred since then?

SS: That record (Satellite) went through the roof and our experiences grew. We were blessed to play in front of so many people around the world. That was 10 years ago. There are so many good and bad things. You know...this industry has taken such a turn. The lack of passion...it's not about the music anymore, about the next hit and the next bubblegum group they can sign. It loses the whole reason why I got into this game, because I know music is powerful. I took time off to get away from music and in that time do a lot of soul-searching and be home with my family and really fall in love with the music again. When it felt right, that's when we decided to get back together and write this record.

MR: So this record is really a reunion.

SS: Yeah, pretty much.

MR: How does this reunion feel so far?

SS: It feels great, man. We never really left. We were doing a lot of stuff that was outside the industry like charity events and outreach that was more selfless that wasn't about the brand or about money or free shows, because we wanted it to be about the music.

MR: Cool, Sonny. What advice do you have for new artists?

SS: Obviously, we've been in this game for 20 years, not that I feel like a new artist, but I do feel like the underdog starting all over again. It goes the same for a new band. You have to love what you do. If you're into this to try to be a rock star and try to be famous, there's no hope in that. It's all kind of meaningless. You'll learn that as you experience this game. You've got to stick with it because you love it, you love-making music. You've got to appreciate the fact that there are people out there that are listening to you that care about your band, and that's a humbling thing. Take it from me, being in this game 20 years, don't get caught up in all of the hype. It will leave you empty.

MR: Beyond empty, dude, and I'll add something to that. To me, the whole conscienceless climbing thing for success with its "ends justifies the means"/"take no prisoners" approach, no matter what good people get hurt, mocks creativity and debases art. Then again, who doesn't want to be a Kardashian, and yes, I'm kidding. But that's just an old person talking, right Sonny? (laughs)

SS: That's how it will be viewed, you're just old. But it's the truth. Stay humble through the journey, enjoy what you do, and don't let it get the best of you.

MR: The latter's the challenge. But the great ones are conscious of life lessons along the way, especially like how to treat people right.

SS: Yeah.

MR: Okay, this discussion kind of brings us to the question what is your relationship with God these days?

SS: It's better than it has ever been. That's why I had to step away from the band and music. Here I was this young kid trying to figure out this Christian thing. There's a different Christian faith all over the world. Sometimes it gets confusing. It became this routine and I didn't want this routine. I dove into the scriptures and I got awesome accountability and I feel more free than I ever have and that's the journey, walking in the presence of God, and being in love with God and not just getting caught up in religion and what you think you're supposed to do; also, just soaking in the grace and the mercy that God has for every single one of us.

MR: So here's the most obvious question. "P.O.D."--how did you guys come up with the name?

SS: When we were teenagers, we were trying to think of a heavy, hard name at the time. Everybody like Metallica and Slayer had the one word terms. Payable On Death is actually a banking term, when someone passes on, what someone leaves behind. We related that to Jesus on the cross, and by his death, our sins are paid, the debt is paid. We have salvation if we want it. We got tired of saying Payable On Death, so we went to P.O.D.

MR: Thanks, man, for sharing with us about your music and faith. Sonny, all the best with the record and your life.

SS: Awesome, buddy.

Tracks:

1. Eyez

2. Murdered Love

3. Higher

4. Lost in Forever

5. West Coast Rock Steady

6. Beautiful

7. Babylon the Murderer

8. On Fire

9. Bad Boy

10. Panic & Run

11. I Am

Transcribed by Brian O'Neal

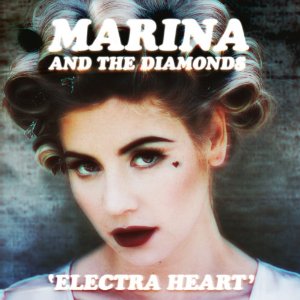

A Conversation With Marina Lambrini Diamandis of Marina & The Diamonds

Mike Ragogna: Hey, Marina. How are you today?

Marina Lambrini Diamandis: I'm pretty good.

MR: Can you go into what you're up to these days? For instance, this Lonely Hearts tour where you've been performing "Teen Idle"?

MLD: I started my Lonely Hearts Club tour in the States about two weeks ago and actually, I've just come off it for some dates with Coldplay in the US, so that's cool. I'm finishing up the Loney Hearts Tour on the East Coast. That's basically what I'm doing. Touring, touring, touring!

MR: "The Diamonds" part of your moniker comes from your last name, which basically means "diamonds" in Greek, right?

MLD: Yeah, indeed.

MR: Can you go into some of your musical history?

MLD: I was never a singer or a songwriter when I was growing up. I knew I wanted to be an artist, a pop artist, but I didn't really tell anyone until I was 19. It was quite a late start. I taught myself keyboard and by 22, I had kind of produced a few EPs, and gigged extensively in a lot of dive bars in London. I got signed when I was 22 with Atlantic Records.

MR: "Teen Idle," from the new album, Electra Heart has an interesting topic, kid of what the title implies. And I believe I've read that you said something to the effect of that between 16 and 20, it's a time of innocence and darkness.

MLD: Yeah. I think that kind of contrast, you know, that's juxtaposition of things in that...people don't really associate innocence with darkness ever. But really, that's what youth is about 'cause as a teenager, you don't know a lot about the world and you have some of your first experiences that will ultimately shape you in that time. You're also trying to establish your own identity and personality against people who want to quell it. It's an interesting time for anyone, and I don't think the experiences are particularly obscure or different. I think maybe I've talked about them or I've talked about very specific things that people usually don't admit to. I say that because, well, I don't want to blow my own trumpet, but I have had so many people who've related to that song and say it's their favorite song. (laughs) I never expect it because it's not exactly a commercial song or anything. It's kind of obscure.

MR: On the other hand, the topic's right on. I know when I look back on my own youth--maybe 16 or 15 through about 21, 22--that's a really wretched period. It is for a lot of kids.

MLD: Yeah, it kind of is. Whoever you are, I think, it is almost like, so many people have related to it. I almost wonder why...maybe we all don't really...but maybe we all take our youth for granted in that. Until I wrote this song, I could get over the fact of being able to forgive myself for having treated myself in a certain way during that time and not really just being able to be a teenager, because those years never come back. If you don't deal with it, I think that you will never grow up. I feel fine about "Teen Idle" now. But for a long time, I felt as if they were unlived years, like they didn't even belong to my life.

MR: Maybe some of the awkwardness that comes from parents is because they didn't understand themselves during that period, and here they go, reliving another shaky period through their kids this time. It's like, "Yikes, here we go again."

MLD: It's so strange! There's a great quote. I think Banksy wrote it somewhere on a wall and it said, "Parents will do anything for their kids except for letting them be themselves." (laughs) I think that's so true. Parents will do anything to protect you and love you, except for let you be you.

MR: Yeah, that's so true. Okay, let's move on to some other songs on Electra Heart, this being your second album on Atlantic. Lovin' "Bubblegum Bitch." There. I said it. Of course, overseas, they have no problem with that word, but in the States, it can still be little bit of a pinch for some people.

MLD: You (also) can't say it on the radio in the UK. It's only in Australia and in Europe, but in the UK, you can't.

MR: Got any personal, fun story on "Bubblegum Bitch?"

MLD: Yeah. When I wrote "Bubblegum Bitch," I had been collecting loads of sassy, but very coquettish--you know, innocent versus evil--lyrics for quite a long time. I went into the studio that day, thinking about what I wanted to write, and I was wearing this pink PVC mini dress, it was from the '60s that I bought on Hollywood Boulevard. On the table was a book called The History of Bubblegum Pop. As my fans know, I'm obsessed with bubble gum pop and kind of subverting that. Yeah, that was the idea for "Bubblegum Bitch."

MR: Marina, who are your influences?

MLD: Fionna Apple, Madonna, Britney Spears, Gwen Stefani...I like PJ Harvey a lot...

MR: Also, it seems when you're performing, you have a "look" or fashion statement that you seem to be making.

MLD: I like to use clothes as props, for example, when I first come on...I like to have lacey gloves on with shimmer-y pipe and baby girl shoes, just to conjure up that sixties, seventies image. It's just basically playing with the humor of the subjects on the album.

MR: You have a song called "Homewrecker."

MLD: I think the message behind that song is because you've been someone who's been hurt...it's about someone who disregards other people's feelings and doesn't really need anybody, or at least that's how they appear.

MR: In addition to being a vocalist and songwriter, you're also a keyboardist, right?

MLD: Uh-huh!

MR: What's your training like?

MLD: Don't have any. I just taught myself.

MR: What do you think is the main difference between your first album, The Family Jewels, and your new one, Electra Heart?

MLD: I think the production is the main difference, it's a lot more polished. Not darker, but electronic as well.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

MLD: I would say don't spend a lot of time on the internet, don't waste your time. I think the worst thing is to have so many different opinions, it's crazy these days. Apart from that, I suppose you have to make music that you're kind of directing and enjoying, because once you're in a band, it almost always ends in a bad way from what I've seen, anyway. Yeah, there's no one particular road that will lead you to success. I think everybody will find it differently.

MR: Marina, have a blast with the tour and the new album.

MLD: Thank you!

Tracks:

1. Bubblegum Bitch

2. Primadonna

3. Lies

4. Homewrecker

5. Starring Role

6. The State Of Dreaming

7. Power & Control

8. Living Dead

9. Teen Idle

10. Valley Of The Dolls

11. Hypocrates

12. Fear and Loathing

Transcribed by Joe Stahl