A Conversation with Thomas Dolby

Mike Ragogna: Hello, Thomas. As you know, this conversation will be in The Huffington Post, but it is also airing on solar-powered KRUU-FM, and you're calling in from a "solar lifeboat," right?

Thomas Dolby: Yes, I am. I have a studio in a converted lifeboat in my garden, which is on the beach facing the North Sea between England and Holland. It's a thirties ship's lifeboat, which is powered by a wind turbine and two solar panels on the roof.

MR: Beautiful. You're very eco-conscious, in addition to being on the side of technology. When did you start incorporating elements of this into your lifestyle?

TD: Well, if you can think back as far as '81, I had a single on The Golden Age Of Wireless called "Windpower" which, in those days, nobody knew what on earth I was talking about. But over the years, people have become a bit more conscious about it and I've tried to keep up. Among other things I do, I'm the music director of an organization called TED or Technology, Education and Design, which is at ted.com. That's an annual get together of people sort of figuring out how to save the planet. So, I'm very well versed in the latest thinking about the ecology.

MR: Let's definitely get more into TED in a bit, but let's first get fans caught up with recent releases. You've had your first two albums remastered and reissued with tons of bonus tracks by the international division of EMI. Were you involved in the process?

TD: Yeah. I guess EMI, being one of the remaining big labels, monitors illegal downloads, and especially those that are on CDs that they no longer have in print, and when there is enough popularity, that gets them to re-release that catalog. So, my first two albums have actually been out of print for a couple of years, and EMI decided that, given the number of illegal downloads of songs like "She Blinded Me With Science," it was time to re-release them. So, they came to me and asked if I would be involved in the mastering process, and I said, "Yes, but there was a bunch of extra material from both of those periods that never actually made it on the album. So, if it's alright with you, I'd actually like to put a new package together."

MR: And it's nice that "Urges" and "Leipzig" finally are restored to the album since they were removed to accommodate the singles "She Blinded Me With Science" and "One Of Our Submarines." Plus, you added the original guitar version of "Radio Silence," demos for "Sale Of The Century" and "Pedestrian Walkway," and many others. It's such a nice celebration of your first album, and that also goes for The Flat Earth that's been expanded and remastered as well. Now, as you said earlier, you're involved with this TED project. Can you go into that a little further?

TD: TED is an annual event that takes place in California, and it's now an annual, global event that takes place in Oxford in the summer. TED has been around for twenty-five years or more, and they were originally a very elitist, Silicon Valley organization. It cost a lot to get into, you had to know somebody, and for four days, it was a lot of rather hedonistic back patting among technologists and investors and so on. When it was taken over by Chris Anderson about ten years ago, he decided to take the great concept of TED and take it out to the masses. So, TED is still very exclusive and very expensive to get into the live event; but at ted.com, you can get downloaded videos on most of the new TED talks, and they're absolutely fascinating. People of all persuasions are completely addicted to TED because it's great for taking on your iPod on your commute or watching while you work out, and it's just fantastic content. It's free, and there's really nothing else like it on the web, especially since there is no commercial or government agenda to it. It's just brilliant people trying to think up ways to make life better.

MR: Have any governments actually used any of the ideas that have come out of this brain trust?

TD: Yes. Ironically, in the U.K., Gordon Brown came when he was Prime Minister to get some ideas, but it didn't help him with the last election (laughs). David Cameron spoke the following year. Also, Bill Clinton came and spoke, and Al Gore came and spoke. In fact, Al Gore actually used TED as a platform to sort of try out his An Inconvenient Truth message before the movie came out, and Al comes to TED every year and is a great member of the community.

MR: Can you tell me how you became aware of TED, and how you became involved with the organization?

TD: I was invited to speak at TED in the early '90s...I had just started developing music software in the Silicon Valley. I was taking a break from music at the time because I was getting kind of fed up with the state of the music business. So, I went to Silicon Valley, and I pursued some interest in technology and actually making it myself, as I had used it for a number of years. The first piece of software I wrote, which was an interactive music program, I was invited to debut at TED. A few years later, my friend, Chris Anderson, took the conference over, and I felt that music served a great purpose at TED because the intellectual stimulation at TED is so much over the course of four days that you really need a pallet cleanser every now and then or something to help you process what you're hearing. I think music is a great little filler and really sets the mood. So, I became TED's musical director, and what I now do is select artists to perform live at TED, some of them complete unknowns that I find on YouTube or CD baby, while others are very famous people like Paul Simon, Tracy Chapman, They Might Be Giants, Regina Spektor, and Natalie Merchant. So, we've had some great performances over the years.

MR: Thomas, in the U.S., we know you more as a video artist than "hit single" artist. Though it was a hit, "She Blinded Me With Science" is one of the most memorable videos of all time in the U.S.; "Hyperactive"--which you just couldn't ply off of MTV with a crowbar--was another brilliant moment for video, and you did some video direction, didn't you?

TD: I directed the "She Blinded Me With Science" video. "Hyperactive" was directed by my friend, Danny Kleinman, and I had a lot of input. But Danny's a brilliant guy. You probably know him best these days as the guy who does the opening titles to the Bond films, which are brilliant. In the early days of MTV, it was very exciting to me that there was a different way to express yourself because my music, in the early '80s, was not initially getting a lot of play on the radio in the U.S.; and to be perfectly frank, I never considered myself a mainstream artist. When I was a teenager, my favorite artists were very obscure cult acts like Frank Zappa, Dan Hicks, Van Morrison, and Joni Mitchell, who were highly respected, but very hard to categorize, and were really a nightmare for the record company marketing guys because they refused to be pigeonholed, and that was what I aspired to be, really. So, it was a real surprise to me when "She Blinded Me With Science" broke the mold for me. I was quite happily going along being an obscure cult artist, then suddenly, I had a Top Five Billboard hit, and it was all over the radio as well. It's really because of the radio being on MTV and the song being played in dance clubs. The song crossed over. That was really a surprise to me because I never expected to be there. Over the years, I've tended to put my commercial efforts in the direction of other artists, but I'm happy to be out there in the lime light, playing with the stars. I've played on a couple of Def Leppard albums, I wrote and produced a rap track for Houdini--which was one of the first platinum selling, twelve inch rap records ever--and over the years, I've done a fair amount of work for other people's records. But my own records, I never really set out for them to be commercially successful. I'm really quite happy if my music is known and loved by just a small group of people.

MR: Well, perhaps it's your fans, I guess more than you, who kind of wish that you had been more of a radio or pop staple. You mentioned before about production and producing other people, and I think most people are very familiar with all the groups you mentioned. But another act that people might know less about is Prefab Sprout, and you were also behind the scenes on Joni Mitchell's Dog Eat Dog album. What was the Joni experience like for you? By the way, you can hear all the Dolby trademark "sounds" all over that record.

TD: Yeah, it was a great experience. I had adored Joni since I was a teenager, and I knew a lot of her songs by heart. So, it was a terrific honor to be invited to work with her. The album was co-produced by myself and Larry Klein--who she (was) married to, and Mike Shipley along with Joni herself. To be perfectly frank, it was a missed experience because I think, being a keyboard player, I didn't want to kick Joni out of bed, as it were. It is her instrument, so, I didn't want to do too much, and I think she referred to it as "Interior decoration of her record," so it was a slightly mixed result. But looking back on it, I think it was a landmark record for her, and certainly a great experience for me, too.

MR: I think Dog Eat Dog and The Hissing of Summer Lawns were major turning points for her. Dog Eat Dog, to me, had so many moments on it that were just brilliant and politically bold, though it pissed off the acoustic and Blue crowds. "Fiction" was a great song, the first eighties song I can think of that took Madison Avenue to task; with "Tax Free," she went after televangelists, and she just did a lot of heavy lifting on that record with regards to social consciousness. When you listened back to that, at the end, how did that record feel to you?

TD: I was very pleased with it, though it was not really what I expected. I mentioned in the past that Joni had had sidemen that influenced a whole period of her work, like Tom Scott during the time he was working with her. I had hoped that I could do the same, but there were a couple of factors against that happening. Larry Klein, who she was married to at the time, was just learning programming and so on, and I had a bit more experience with sampling than he did, so he was eager to pick up on that. I think beyond that record, Joni and Larry really took off with the sampling thing, and did a couple more records like that. But when I listen back to it, it was a time when Joni was, for one, angry with the world, and two, felt like enough of an activist that she could be a fly in the ointment and sort of do something about it. I think, sadly, while her most recent stuff has some very beautiful songs, she seems to have given up the hope, somehow, of ever changing the world, and that's sad.

MR: Yeah, although, after we worked together on a box set of the Geffen albums, I also worked with her on a project called The Beginning of Survival which was intended to help try and affect change. I remember Joni called me at three o'clock in the morning because she had been listening to Pacifica Radio, which is this station in California that you're probably aware of, right?

TD: Yeah.

MR: Well, she calls me at three in the morning and requested Universal to do something about getting her music played on the station more since some of her contemporaries' music was being played between interviews, news stories, etc. So, we conspired to assemble a new collection that focused on her socially conscious material as a way of reintroducing it to the public and stations like Pacifica. That was the genesis of The Beginning Of Survival. In my opinion, that body of music represents a period when Joni did believe she could help enlighten and affect the world. I think people should really try to listen to this set because one might just get inspired by it, and there are a couple of viewpoints presented that I know the public hasn't really thought of yet.

TD: The thing is though, Michael, how many people get affected by music that becomes popular? And then, there's another metric, which is how deeply are they affected by the music that they hear? When you see the charts and look at radio playlists and you see who's popular, I think it's kind of hard to gauge, sometimes, how far something has gotten under their skin. I think, to me, one of the great testaments to Joni Mitchell's life and her work is that generations of female singer-songwriters since would put her right at the top of their list of their biggest influences--in their lyrics, in their music, and with their vocalizing. So, there is no fair metric by which to gauge the influence and the importance of somebody like Joni in the world.

MR: That's so true, isn't it? And she loves a debate.

TD: Absolutely.

MR: Thomas, let's talk about what you're working on lately. You're recording a new album, but you also have EPs of some songs that will be released before Christmas. Can you give us a look into how you're recording it, the musicians, all that?

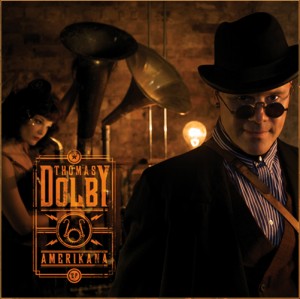

TD: Well, it's my first new studio music in nearly twenty years, and I've written most of the music in England in the wheelhouse of my solar powered lifeboat looking out over the North Sea, which is a very inspiring place to be. It's been great to get back into music after quite a few years away in the Silicon Valley where I was doing the tech entrepreneur thing. I found that, making these new songs, I had very little interest in doing groove, sample, or sort of sequence-based music. There's tens of thousands of people out there doing it, but what's very rare is a great song, a great melody, or a great lyric, and I think that's what sets me apart. So, in my maturity and wisdom, hopefully, I have focused on the songwriting itself, and these are songs that I could sit down and play you on the piano, and you'd get a full impression of them. So, there's less focus on the production bells and whistles, and more focus on the essence or the source of the song itself. I'm about halfway through the album and it should be out early in 2011, but in order to keep the level of interest up on the Internet that has existed, even all these years I've been away, I decided to sneak peak preview these songs to my fan base online. So, if you're a member of my online community, which is called The Flat Earth Society, you can get early access to some of these songs. And the first EP, that has just been released, is called Amerikana. There are three continents on the album, and the first is Amerikana. So, this is really an affectionate look back at the twenty years that I spent living in the U.S.A., and some of the great roots music from the heartland. But it's definitely got an English, ironic twist to it.

MR: Speaking of your Amerikana EP, I love the set up to your song "Road To Reno": "...you know you're going on a wild ride when you have a crooked politician and a woman who sold brassieres at Sears."

TD: Yeah, and it's kind of a road movie idiom, but it's directed, not by Quentin Tarantino, but by Guy Ritchie.

MR: When you're composing songs, do you write them for the purpose of a project or are you just always writing?

TD: I think I'm very conscious, when I write a song, of where it's going to go, and what the audience is going to be. My creative process usually starts with closing my eyes and visualizing a stage with an empty spotlight on it, and somebody walks into the spotlight and starts singing a song. What does it sound like? What would I like it to sound like? How is the instrumentation? What about the lyrics? So, I tend to work backwards like that, and not from the bottom up. If I'm writing a song for my new album, then I'm sort of thinking about where it's going to go in the running order, and how it balances with the rest of the songs on the album. So, yes, I am usually quite conscious. But having said that, little ideas also come to me in the airport lounge, in the shower, driving my car, walking on the beach, feeding my cats or whatever it may be. These things come to me and won't come out until I find a home for them.

MR: "Airwaves" is probably my favorite Thomas Dolby recording, though I've been trying to figure out the storyline for years. I have quite a few interpretations, but what did you write the song about?

TD: Well, in the first instance, it's not always good to put the record to the true background of the song because one of the lovely things is that people fill in the blanks themselves. So, I think part of the role of a great song is that it provides a blank canvas where people can fill in their own emotions. "Airwaves," I think, is a song which really is about the deep love and attachment that can come from a very stressful situation--like a wartime situation, under pressure. So, I think that's really what it's about. A lot of the symbolism in the song is just really sort of a poetic view of a wartime situation--the noises outside, the danger in the street, the idea that you're hiding away, that your freedom is being restrained, maybe even taken away altogether, and the risk of being torn apart from somebody that you love. That's really the backstory to "Airwaves." I suppose in some of the details you can see this grim, sort of Blade Runnner-type society somewhere in the future, which is the backdrop to the lyric.

MR: Right, which also runs through some of your other songs like "One Of Our Submarines." Also, on The Flat Earth, "Dissidents" was, I think, one of your more socially brilliant pieces.

TD: In a way, I sort of identify with the Russian dissident writer type, who, in spite of adversity, is determined to speak his mind. Again, it's a situation of living that adversity or living with the fear of being shipped off the Siberia. So, on the surface, it's a somewhat heroic song about escaping over the border. But I suppose the subtext really is, as an artist today, in a supposedly free society, I want to be able to say what I feel, and I want to be able to write the things I feel without feeling hemmed in. In this case, it's not by a repressive government, it's by the norms of the commercial music business; radio programmers telling me that there are too many guitars on the songs, and things like that. So yeah, "Dissidents" is definitely a heroic song, and a good one to kick off The Flat Earth.

MR: "I Scare Myself" was your cover of the old Dan Hicks song, right?

TD: Yeah, that's right. It was a Dan Hicks song, and the way he used to do it was sort of up tempo. But I put a spooky, kind of downtown mood behind it, so I covered it that way.

MR: You also had "Hyperactive," which we spoke about a little bit earlier. That video was pretty ground breaking, and for our readers it was the one with the cube headed kid. Did you write the script or was it already scripted for you?

TD: I sort of worked it out with Danny Kleinman. I'd had this idea about the cube head for a while, but we were in the early days of video effects, so it was kind of exciting to mix the physical effects of the cube head with the early digital effects.

MR: You know what's beautiful? You change your artist image from album to album. On ...Wireless, I would say you were a scientist or in the very least, a science student. Then, on The Flat Earth, you became a kind of archeologist.

TD: I think, on the second album, I definitely felt like a pioneer, an archeologist, or an outdoorsman rather than a scientist.

MR: On Aliens Ate My Buick, well, I don't even know how to classify the character, really. You were just having some goofy fun on that, and it was all groove-centric.

TD: Well, it was really a postcard from America back to England because I had just moved there, and I had this great touring band that I put together that I found in the pages of Recycler magazine. We were playing a lot of clubs up and down the West coast, and the grooves on that album really grew out of touring with that band.

MR: The album features a great collaboration that you credited as "Dolby's Cube." What was its origin?

TD: You know, I wanted to do a fun track that was maybe a little outside the norm from what I would usually be doing, and that was "May The Cube Be With You," which featured George Clinton--who I had already collaborated with and co-produced some songs for his album--and Lene Lovich, who I used to play keyboards for. So, between the three of us, we did Dolby's Cube, and the song "May The Cube Be With You" and an accompanying video.

MR: And you wrote Lene's "New Toy."

TD: That's right.

MR: Now, you played the Grammy awards one year with a variation of Dolby's Cube, right? Who was a part of that?

TD: George Clinton wasn't in it. It was myself, Stevie Wonder, Howard Jones, and Herbie Hancock, and we did a sort of synth medley in '85 at the Grammy Awards.

MR: It was a great moment because it was like the music business' acknowledgment that, yes, we have other musics that should be spotlighted in that setting.

TD: Well, radio, in those days, was still playing a lot of FM rock bands, and synths were fairly novel still, so they had to play a medley with one hit by each of us followed by The National Anthem.

MR: Then you waited quite a few years and out comes Astronauts And Heretics, which is another brilliant album. I remember when it came out, there were many associated EP singles. I've wondered if you over recording for that album or if each time you released a single, did you record more material?

TD: Every time I mixed one of the songs, I would do sort of an alternate version of it. That's when record companies were really big on having multiple imprints of each song or different versions with different single packages, and so on. That was all just an effort to get better chart positions. That's one of the things that was upsetting me about the music industry, at the time, was that it felt really bloated, and I needed a chance. So, that's really why I decided to go to Silicon Valley for a break, and pursue my own interest in technology. I formed a company called Beatnik, which, for years, did really, really cool stuff that made almost no money at all, and then ended up doing quite uncool stuff, which made lots and lots of money. We created the ring tone synthesizer, which is in every Nokia phone, and that became our business. That's a much less interesting business to me, which is why I got out of it, and headed back over to England to get back into my musical roots.

MR: You know, I was always surprised that the whole ring tone thing took off like it did, though it was obvious the kids were going to love it. Why do you think people gravitated towards them?

TD: Well, it's like having a certain brand name on your sneakers or your clothes. In fact, the music business was very confused at the time when ring tones first took off because they couldn't get people to pay a buck to buy a song for a download, but people were happy to pay two-fifty for a little dinky version of the song to put on their cell phone. The reason was that it wasn't the music budget it was coming out of, it was the fashion budget. If you are a fifteen-year-old kid standing in the mall and your phone goes off, you want it to sound cool. It's just like the fact that you can get a perfectly good pair of sneakers for twenty bucks, but you'll pay fifty-five for the sneakers with the brand name on them. So, I think it's just a piece of exhibitionism that means people, in their vanity, will pay money to put a ring tone on their phone.

MR: Let's get to your new album. What's the name of it?

TD: My new album that I'm working on is called A Map Of The Floating City, and it's going to be out in early 2011. I've been working on it for a couple of years already, and I've very into it, but I can't quite stay up and burn the midnight oil like I did when I was twenty-one because I've got a family and responsibilities these days. I've been working on it in my lifeboat, looking out over the North Sea, and the title has a couple of connotations to it. I'm very close to one of the largest commercial container ports in Europe, so I see these enormous container ships going in and out of the port headed for the continent, and when the light hits them in a certain way, in profile, it looks like the Manhattan skyline. I'm sort of looking out at this archipelago of built up islands across the horizon. I found out that in Tokyo, back in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the merchants in the harbor, with their rafts and barges, got into such gridlock in the harbor that they eventually stopped moving altogether, rafted up all their barges and created what was called The Floating City. This was really a den of sin and iniquity, where you could get salts, spices, and all sorts of sexual deviations. So, that was sort of the second connotation. I suppose the third connection is that the floating city is like a parallel universe that's all around us, and it's like a spiritual plane that music can transport us to.

MR: Also, if you're old enough, you have another connection with floating cities, which would be Roger Dean's artwork.

TD: Yeah. Well, a floating city is definitely a sci-fi sort of image. You sort of think of blimps and dirigibles holding up the city.

MR: You also have a game that's going to be associated with this record, right?

TD: Yes, it's a little too early to talk too much about it, but there is a back story to the album, and I'm actually releasing three digital EPs on the way to the album. They are: Amerikana, Urbanoya and Oceania. Amerikana is really it's own EP, which my fan base can listen to today. Urbanoya is sort of a dark place because I'm not a city person, and then Oceania is a submarine, tranquil, and beautiful place, like the place I currently live with my family. It really is the happiest and the most comfortable of them, and yet there is this sense of impending doom because it's not very high above sea level, and there is fear that it will disappear with global warming.

MR: There's a subject. Global warming. Technology-wise we might be able to be aggressively going after this problem, but it kind of seems, as a society, that we're just letting this run rampant, don't you think?

TD: Well, it's a very sad thing. I'm not a political activist myself, though I am very involved with TED. I tend to be the fiction writer or the person that imagines alternative realities, and that's kind of what I'm doing with A Map Of The Floating City. The game is actually set in the future, when there has been a climactic disaster, and the survivors of this catastrophe are clustered together in this place which is cool enough to live comfortably on the planet, and that's at the North Pole. Huge portions of the land mass have been submerged, so the northernmost parts of Amerikana, Europe, and Russia are still accessible, but people have been requisitioning these big container ships and tankers, and they've gotten to the point of gridlock at the North Pole. So, this sort of rafted city has kind of come into being, and that's the floating city in the game. I don't want to talk too much more about it, but if you play the game, you will unravel the secrets of the floating city.

MR: Who is playing on the EP's track "17 Hills?"

TD: Well, "17 Hills" has got some great musicians on it, among them, Natalie MacMaster, who is a fiddle player, and Mark Knopfler, who is as you know, the former front man and guitarist for Dire Straits and one of the worlds greatest guitarists. I pretty much constructed the song with him in mind, and what was wonderful about Mark's guitar playing is that he really helped tell the story; and like me, he's a Brit who often lives and functions in the American world, and yet his voice somehow has the credentials to be a storyteller in an American setting.

MR: This EP is initially going out to your fan club, right?

TD: Yes.

MR: And speaking of "clubs," please would you take us back to your history with Bruce Woolley & The Camera Club?

TD: Well, that was my first professional gig as a musician. Up to that point, I'd been working as a sound engineer doing live sound for punk bands throughout London, and I'd been working on my keyboard chops, and Bruce was the first guy to really spot my skills and hired me to play in his band. We had a very brief brush with stardom in the early days with the new romantic movement, but Bruce had formerly been partners with Trevor Horn who formed The Buggles. We each had a version out of the song "Video Killed The Radio Star," but ours was a slightly rockier version, while theirs was kind of poppy and gimmicky, and it became number one all around the world. I've stayed friends with Bruce throughout the years and he's a great guy. In fact, he's a great theremin player. I've done some co-writing with him over the years, and he's continued to work with Trevor as a writer. He wrote things like "Slave To The Rhythm" with Grace Jones, and he's played live with me on many occasions.

MR: You were also on Foreigner 4, right?

TD: I was, indeed. I played on things like "Waiting For A Girl Like You," and "Urgent."

MR: Unless we've forgotten something, I'm not sure what else we can talk about until your new album comes out, when I'd love to have you back.

TD: I think we've covered most of it, but by all means, ping me in a few months, and I'll talk specifically about the album.

Tracks:

Road To Reno

Toad Lickers

17 Hills

(transcribed by Ryan Gaffney)