Originally published by the Medill News Service

Joakim Noah crouches in the center circle, squatting over the Bulls logo in the middle of the United Center floor. Chris Bosh walks over and faces him, with his hands on his hips. The timekeeper puts 12 minutes on the clock.

Two of the Eastern Conference's reigning All-Star big men prepare for the jump ball, a play as old as basketball itself. Wilt, Kareem, Shaq -- all the greats started their games the same way. So the opening of tonight's battle between the Chicago Bulls and Miami Heat feels just like any other game from any other era.

Except this is December 2013, so six SportVU motion-detecting cameras overhead will capture every movement from the jump ball to the final buzzer. This is the year everything in the NBA has changed.

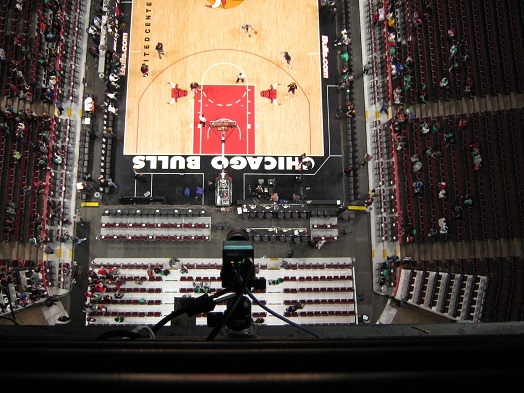

Starting this season, six SportVU cameras like the one shown above capture

the action inside every NBA arena. Photo: Courtesy of STATS

PART ONE: SPORTVU CAMERAS IN EVERY NBA ARENA

Fewer than 20 miles northwest of the arena, in an office building in the suburb of Northbrook, somebody is monitoring the data spit out by the cameras.

"There's typically somebody here 24/7," said Brian Kopp, senior vice president of sports solutions at STATS LLC.

STATS is the company changing the game. They make the cameras. For this data mining collective, 2013 has been a coming out party of sorts.

"We started in the '80s as a baseball data company," Kopp said. "We've always been around primarily as the facilitator. If a media company or a team wants to do analytics, it all starts with access to data. And more often than not, they'll wind up talking to us."

When Kopp arrived at STATS a few years ago, the company pushed to improve what he calls "unique content." One major result is the SportVU (pronounced sport-view) camera.

Six motion detecting cameras now film the game at 25 frames per second from the rafters of every NBA arena. They track every player and the ball, enabling statisticians to compile data and turn it into usable nuggets.

New data sets can offer more context. If a player grabs six rebounds, it'll be in any box score. SportVU can also determine how many rebounding opportunities he had. If he took 20 shots, SportVU will know how many he created for himself and how many were set up by teammates. Plus how many of each he made.

SportVU cameras have tracked NBA data for a few seasons, but two major changes thrust it into the spotlight this year.

First, it's no longer voluntary. The NBA made sure every arena was outfitted this offseason.

Second, NBA.com started featuring the stats prominently. Data the teams had previously guarded in secrecy is now available to the public.

"We're excited just because it's something we've been working on for years behind the scenes," Kopp said. "To us, the exciting part is that this is just the starting point. There's a lot more to it than what people see on the site."

The stats are now a part of the mainstream conversation too, not relegated to the deep corners of the Internet. Bill Simmons included separate SportVU "revelations" about 13 different teams in one recent column. Isiah Thomas and Vinny Del Negro discussed it on NBA TV in November.

While fans may understand the impact of the technology better because they can see some stats online, or read Simmons' take on them, Kopp said it's that first point that matters the most.

"Everyone has it," Kopp said. "It's not going away. It will start to influence the way people make decisions. There's been a change in the conversation. It's less about 'Should we do it?' and more about 'How will we use it?'"

And Kopp thinks the teams quickest to adopt it will get a leg up.

"If they don't want to use it," Kopp said, "they may be missing out on an advantage that another team's going to get over them."

Meanwhile, back in the United Center, the Bulls are playing once again without Derrick Rose. The former MVP has a torn meniscus. A decade ago, the Bulls might have focused on how to replace the 20.8 points and 6.8 assists per game he's averaged for his career.

SportVU offers a deeper look. During 10 games this year, Rose touched the ball 83.2 times per game, 74.6 of them in the front court. He held the ball for more than 6 minutes per game, among the top totals in the league. His assists created 15.2 points per 48 minutes of action. This is the production the Bulls need to replace.

Rebounding is one key to any game. The Bulls enter this contest third in the league in total rebounds. The Heat are dead last. But there's a problem with "counting" stats, which measure accumulation, as opposed to "rate" stats, which measure frequencies. The number of three-pointers a player makes doesn't mean much if you don't know how many he's attempted.

The number of possessions per game, field goal percentage and defensive field goal percentage all affect rebounding totals. So the Bulls' leading rebounders, Carlos Boozer (8.8 per game) and Noah (8.4) may grab more per game than Miami's Bosh and LeBron James (5.8 each). But SportVU shows that Boozer and Noah only come down with 64.2 percent and 52.8 percent of their total rebounding chances, respectively. Bosh and James grab 60.4 and 72.2, respectively. SportVU data exposes efficiency.

Sample size is the scourge of the analytics movement. Expanding the SportVU technology to every NBA arena doesn't make the data more accurate, it just makes the samples larger and more meaningful.

PART TWO: COLLECTING THE COLLEGE DATA

A horn sounds, and Shane Battier checks into the game. Boozer, Luol Deng and Mike Dunleavy Jr. are already there.

The court can only fit 10 players at a time, and for the final 12.9 seconds of the first half, four of them are former Duke Blue Devils.

Battier was selected sixth in the 2001 draft. Dunleavy was taken third the following year, when Boozer slipped into the second round. Deng went seventh in 2004.

The NBA draft can be a crapshoot. Michael Jordan was once picked third. Boozer, a two-time All Star, was taken five picks after Steve Logan, who never played an NBA game.

Boozer, Dunleavy and the other 55 players from the 2002 draft were scouted meticulously. Forty-four were drafted from the NCAA level. Scouts roamed the country analyzing college players, but couldn't dream of having access to the type of data SportVU now collects in every NBA arena.

This, too, is changing.

On Nov. 12, Duke, Kansas, Kentucky and Michigan State descended upon Chicago for a double-header loaded with NBA talent. ESPN's draft analyst Chad Ford tweeted that 16 potential first-round picks saw action.

And as the teams played in the United Center, the SportVU cameras clicked away.

To run the cameras during college games, STATS coordinated with the NBA and the Bulls. Kopp said they don't need permission from schools or conferences.

But three college teams have signed up with STATS to join the data mining expedition: Duke and Louisville, which had their home arenas fitted with cameras, and Marquette, which shares an arena with the NBA's Milwaukee Bucks.

A sampling of teams that will play road games against Duke, Louisville and Marquette

with the SportVU cameras rolling this season. Graphic by Mitch Goldich

Throw in teams that play some (like Villanova) or all (like Memphis) of their home games in NBA arenas, plus 2014 conference tournaments and NCAA tournament games in NBA arenas from San Antonio to Orlando to New York City. Suddenly the vast NCAA landscape seems more scalable. Even if not all those games are recorded -- STATS says it isn't a certainty they will be -- Kopp expressed a desire to expand within college basketball. So the future feels imminent.

Most teams remain extremely guarded about discussing the SportVU technology and data -- the Bulls declined an interview for this story -- but with so much riding on draft day decisions, savvy general managers ought to be salivating over access to this information about college players.

PART THREE: SPORT SCIENCE UNDER HOLLYWOOD LIGHTS

The Bulls announced a crowd of 22,125 for the Heat game, but not everyone spends the whole time in their seat. As halftime rolls into the third quarter, eight fans camp around a television in the concourse above section 329. The Houston Texans and Jacksonville Jaguars, with a combined record of 5-19, are playing a mostly meaningless football game -- neither team has a chance at the playoffs.

LeBron James, perhaps the greatest athlete of his generation, perhaps the greatest basketball player of any generation, is in the house. His otherworldly talents are on display for 33 minutes of game time. Yet a subset of fans in the arena care more about whether or not Cecil Shorts III will score a touchdown for Jacksonville.

Inside the arena, the Bulls cope with the loss of their best offensive player. On a TV screen in the concourse, so do the Texans. Arian Foster, the NFL's 2010 rushing leader, has missed four straight games. The Texans have lost them all.

Foster is a unique specimen. One of his strongest attributes is the ability to make quick lateral jukes. When Foster cuts, his foot bends up toward the shin, and he makes initial ground contact with the inside of his foot. That maneuver enables him to explode out of a cut with up to 4 Gs of acceleration.

This is not obvious to most onlookers. The observation was made in ESPN's Sport Science studio.

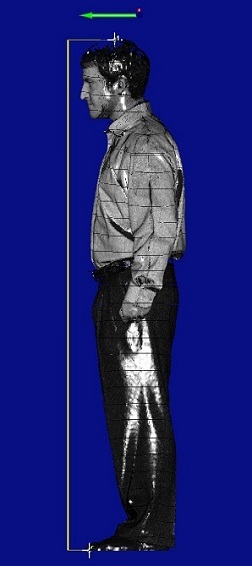

A look inside the Sport Science studio-slash-science-lab, where they film

segments for ESPN. Photo by Mitch Goldich

Pull open the front door to the Sport Science office and the first thing you see is a tall trophy case stocked with Emmy awards. After all, this is Hollywood. Well, Burbank. But you get the idea.

Sport Science is a division of BASE Productions, a company that owns nearly two dozen properties specializing in reality, documentary and unscripted television. Not all of its Emmy wins are from Sport Science.

The Sport Science command center is a hybrid science lab and television studio. Most sports fans know about it thanks to the host John Brenkus, who hops on "SportsCenter" to narrate segments with athletes in the studio, or break down top plays from various games.

"We think of it as equal parts science and entertainment," said associate producer Eli Baldrige. "We have to determine what will be entertaining for the audience from a scientific perspective."

Inside the building, Sport Science has a football field, a basketball court and props ranging from tackling dummies and punching bags to motion sensors.

Like STATS, Sport Science is in the data collection business. But the company gathers a lot more research in the lab. Before working out, athletes stand on a scanning machine that takes a three-dimensional image and calculates everything from wing span to calf girth. That's how Sport Science discovered Julio Jones' left arm is longer than his right.

Jones, the Atlanta Falcons' All-Pro wide receiver, never knew that until Sport Science told him. So when Jones laid out to make a one-handed grab with his left hand during a week five game against the New York Jets, Sport Science might have been the only group in the world with that information handy.

Jones' in-studio segment has yet to air because of his own season-ending injury, but producers said he had a productive visit. The professional pass-catcher performed some tests, and then broke the Guinness world record for longest completed water balloon toss. The still-full balloon, now autographed, sits in a case on an office desk. No matter how long the balloon lasts, the data isn't going anywhere.

And just like SportVU is making a run at collecting data from college players, so is Sport Science. Prior to the 2013 NFL draft, 30 soon-to-be NFL players came to the lab for testing. Sport Science hopes to have 50 players in next year.

"Unlike the NFL Combine, we put them through tests that are a closer representation to their on-the-field ability," Baldrige said.

And Baldrige is proud to point out that Sport Science gave high grades to Colin Kaepernick, Luke Kuechly and Jason Pierre-Paul, who all blossomed into stars at the NFL level.

Sport Science is building up a database so that next year's prospects like Teddy Bridgewater and Johnny Manziel can be compared to recent draftees like E.J. Manuel and Russell Wilson.

Just like with the NBA data, sample size creates context.

And because it makes for great television, sports fans take in a weekly dose of analytic numbers that reveal athletic potential.

Right: Sport Science usually takes a 3D scan to measure athletes' bodies. The machine can handle reporters too. Photo: Courtesy of Sport Science

PART FOUR: PRO FOOTBALL FOCUS REWINDS THE TAPE

The football game is mercifully nosediving to its conclusion. The Jaguars are close to blowing a game they've controlled all night. But it doesn't really matter. These fantasy football players care about seemingly every number except wins and losses.

Back in the basketball game, the Bulls are pulling ahead by 20 points on the defending champion Heat. In the concourse, the action is more tense. The beer taps say Goose Island, Sam Adams and Shock Top. Bottles of Crown Royal whiskey line a shelf behind the bar like a pool of fantasy players waiting to be drafted.

Sure, the game is on TV. But this beats the cheap seats, where the vendors are peddling light beer.

A Matt Schaub interception is greeted with cheers and high-fives. One fan is playing against running back Ben Tate, and the interception will keep the ball out of his hands for a while. The fan pulls out his phone and launches a fantasy football app.

"Ben Tate's projection had to be higher than 11," he says hopefully.

Fans like him are conditioned to think in terms of expected value and win probability whether they realize it or not. Inside the arena, these are the same principles NBA teams are using to think about shot selection and lineup optimization.

With 3:45 remaining, down by four points, the Texans fail to convert a fourth-and-2 at the Jaguars' 13 yard line. The one-week-old New York Times Fourth Down Bot, a computer program designed to do a cost-benefit analysis of fourth down strategies, soon tweets, "It didn't work out for the #Texans on that 4th and 2, but from where I'm sitting, it was a good call." The tweet of support is likely to offer little solace to Texans' coach Gary Kubiak, who was fired after the game.

The Times' robot uses a model created by Brian Burke, who founded Advanced NFL Stats. His website is one of many dedicated to using math as a better way to understand football.

Another site that has gained popularity in recent years is Pro Football Focus.

"There's been a lot of growth in the last year," said PFF's editor-in-chief, Rick Drummond. "It wasn't embraced from the get-go but it didn't take long for people to see that there was value."

PFF is similar to STATS, in that they break down every play to the smallest level possible. But instead of high-speed cameras, PFF does it the old-fashioned way -- rewinding the tape over and over.

PFF tracks two things -- player participation data and player grades. The company's seasoned analysts grade the players, while a group of college students and 20-somethings keep track of who's in the game on every snap.

More accurately, PFF seems to be where SportVU was two years ago -- with some teams secretly absorbing the data and others failing to hop on board. PFF hires teams as clients. And like SportVU before the NBA put the cameras in every arena, the only teams with access to the data are the ones willing to pay for it.

PFF also has packages available for fans, who can purchase the stats on their website. Drummond said many NFL players even buy subscriptions just like regular fans. The snap counts are all objective, but if a player isn't happy about his grade, well it's not unheard of for PFF to hear about it.

"We offer a lot of stuff for lineman, who don't really have stats anywhere else," Drummond said. "They can't go to ESPN and find stats for themselves on there. They're people -- they like looking at their own stats. Everybody does. It's not just running backs and receivers who like looking at their numbers."

It's also front office members who want the data.

"There's a big difference from one team's analytic department to the next," Drummond said. "I think everyone's getting on board but they're not all there yet."

Drummond wouldn't divulge whether the Texans or Jaguars are on his client list. Teams pay for both stats and client anonymity. But the New York Giants are on the list. The Wall Street Journal published a story about the Giants' use of PFF the day before they beat the New England Patriots in the 2012 Super Bowl.

"There were phone calls that followed immediately," Drummond recalled.

Drummond said some teams use the data in player evaluation, while others use it to study tendencies for the purpose of in-game strategy. And since more information is available for teams than what appears on the website, the teams missing out likely don't even know what they're missing.

THE DETRACTORS

Wherever there are champions of analytics, there are also detractors.

"There are always going to be people that are against it," Kopp said. "Not even necessarily old-school people, but people who feel it takes away from the art of the sport. To me that's not the point. The point is, just like in everything else you do, more information is better if you use it the right way."

Almost every stat was, at some point, new. The NBA started tracking steals and blocks in 1973. The NFL didn't keep track of sacks until 1982. So drives per game, free throw assists and opponent field goal percentage at the rim still have time to catch on.

With 3:58 left in the fourth quarter, Luol Deng hits a three-pointer to put Chicago up 17. With 1:50 remaining, he hits another three to put them up 20. There will be no Miami comeback. The Bulls will win 107-87.

Is Deng simply in the zone? Is he riding the wave of a statistical anomaly? Or is he merely shooting from the spots on the floor where empirical evidence says he'll make the most shots?

It's hard to say.

That's the thing about data and analytics in sports. It doesn't tell us what will happen, only what is most likely to happen.

Sport can be beautiful, and unless your job is to create a model that will bring your team a championship, the unpredictability can be one of its most irresistible appeals. Fans buy tickets or watch on TV because nobody knows what will happen.

But the data gives us a better idea. And more and more groups are racing to collect it.