Could it be the same one -- the comb whose teeth had just glided through our sons' wet hair? I was stunned to see its tiny image among a jumble of snapshots in a shoebox, the remnants of an overseas trip cut short nearly 20 years ago when I had to fly home to my mother, who was gravely ill. It turns out this scuffed tool, which I thought contained no memories, has been with me every day since my late adolescence. Now for a decade it has been smoothing first one, then two boys' heads. The comb is gentle; they ignore the intrusion after every bath, like lion cubs who keep batting each other despite their mother's grooming. They are people I couldn't have imagined that somber night when I took the picture which captured the comb, and our family lives along streets I'd never even heard of then.

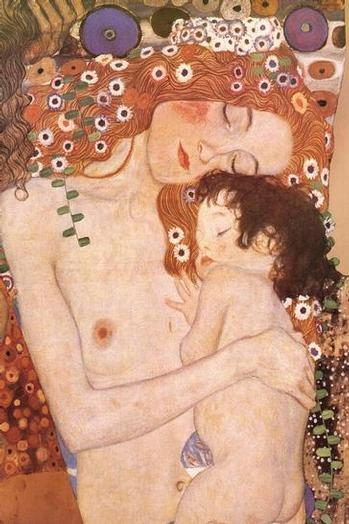

The photos in the shoebox convey my first joyful week in Vienna -- iconic buildings, swirling Klimt paintings, crowded cafés, new friends arm-in-arm -- and then my suddenly final night in a lonely dorm room: shots I took of the narrow bed and half-packed suitcase; the desk with travel phrasebook; a sternly Germanic elevator sign: "Alleinfahren von Kindern unter 12 Jahren verboten" (children under 12 forbidden to ride unaccompanied). The last photo on the roll is my own sad face, very small, the camera held at my cheek, reflected in a mirror above a shelf on which rests a jar of Noxzema and the very same purple-and-green-toothed plastic comb.

Earlier that day, enclosed in a wooden phone booth -- it was 1993 -- I fumbled with Austrian coins and barked questions across the ocean at my mother's doctor and her dearest friend. (I am an only child with parents divorced by then.) The wise friend insisted I come home immediately, but it pained me a little to end my summer adventure. In my primitive German and most bureaucratic English, I withdrew from the language school where I'd just enrolled and rode a trolley to Austrian Airlines for an emergency ticket. I found that in a crisis I was brave and competent, but also somewhat resigned; it was more bearable that way. The next morning, waiting to board the plane, I saw that I'd never filled out the emergency contact section of my passport. While I still could -- while she was still alive -- I wrote in my mother's name and number. I don't know if that was a form of prayer or anticipated memorial.

Weeks later, after her death, and for many months, I didn't disturb the things -- the notebooks and Pilot pens, the half-edited typewritten pages -- she'd left on her desk. For years I barely opened her closet -- the pencil skirts and silky blouses from Bloomingdale's faintly perfumed by Caleche, the high heels standing around on the dark floor. I wanted her to be there in the pockets of air hovering near her possessions, still placed where she'd placed them. (Yet I was not denying her death -- the huge, sad truth of it had quickly reached right down to my dreams.) Even unused, her trademark possessions and daily tools helped me shape a new, forever altered life of my own.

My humble comb tagged along into that new life and new home, but more elaborate old tools outlast their purpose when they don't fit our easy, informal ways. In a junk shop our younger son unearthed a manual egg beater half a century old. He turns its red Bakelite crank just for the clackity sound it makes; when there are eggs to beat, we use an electric mixer. My grandmother had a table-top crumb sweeper whose bristles were hidden behind brass filigree and faux pearls; to me in the '70s it seemed fantastical as a ball gown. By then she herself had stopped using it but she'd kept it, and my mother kept it after her. These are evocative objects -- I'll surely keep them too -- but soon we'll need re-enactors in period costume to explain how they were intended to be used.

Now, smooth tools glowing with digital intimacies (photos, playlists, "friends") have become extensions of ourselves. If we misplace them we are thrown into a panic. They rarely show signs of age because they are not meant to last, and they won't. Still, my mother, had she reached the present, would be using these tools herself. (In the early '90s the computer was inspiring her to write again; maybe its screen-floating words felt freer than the stamped ones of a typewriter.) She would've sent the wittiest emails, and texting would've recalled the short-hand she had jotted on steno pads at work in the late '50s.

Old things that we salt away, like my ornate crumb sweeper, can embody a disappeared past, or they may reveal unexpected signs of continuity, like my snapshot which caught a glimpse of the comb. When I was ten years old, I used to photograph hotel rooms before we checked out, enjoying the whiff of finality in "I'll never see this again." The photos I took at twenty-four of my Viennese dormitory were rooted in that, but I knew there was nothing romantic about my leave-taking. I understood what was happening to my mother; what was going to happen.

That last night in Vienna a German phrase came into my head: "Ich muss allein fahren"--like what children were forbidden to do by that elevator sign. "I have to ride alone." For a while, without her, I did. But seventeen years later, gratefully enmeshed in the unique passions of my own family life, I don't ride alone. And the comb has a houseful of heads to ride over.