[This post was previously published in the January 29th edition of Forward, and you can view all the covers discussed in this blog there].

I knew there were a lot of "Holocaust-related memoirs" but how oft-rehearsed the genre was I learned only when I added to it.

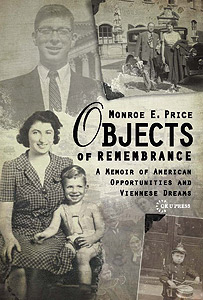

Born in Vienna in 1938 and a fleeing infant refugee just seven months later, I am a prime example of a demographic that is determined to tell its story while it still can. On the publication of my book -- "Objects of Remembrance: A Memoir of American Opportunities and Viennese Dreams" -- I was struck by an odd fact. Just as there is a family of Holocaust memoirs, there is a particular and definitive style that characterizes the genre's covers or dust jackets.

Thanks to the Internet, I could check many specimens of this literary form to confirm my intuition. Patterns quickly began to emerge from the flood of grainy photographs aimed to teach about a reachable but distant past.

Taken together, the covers provide a twisted and extraordinary family album of a version of a disappeared European-Jewish past. Indeed, the graininess of the photographs -- a film that obscures -- provides a sign of something that has vanished: a person or a place, relatives or the next town.

Certain tropes appear frequently -- styles of images that embellish book after book. A notable, obvious one is the nostalgic depiction of young siblings, with the tragic implication that one lived, one did not. The cover of Never Far Away: The Auschwitz Chronicles of Anna Heilman, is an example, as is Anita Lasker-Wallfisch's Inherit the Truth: A Memoir of Survival and the Holocaust.

Thomas Buergenthal's A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy captures narratives of tragedy and consummate hope. Before we get to the introduction by Elie Wiesel, we pass a cover showing a young boy, bright and blessed, who could not know what tragedies would intervene between a blissful childhood and a future in which he would become a renowned international jurist. The cover shows him and his model parents in a model setting, a trio in prewar bliss.

Affecting are the prevalent graphic depictions of iconic symbols: yellow stars and barbed wire, railroad cars and tattooed numbers. Paul Steinberg's Speak You Also: A Survivor's Reckoning and Alter Wiener's From a Name to a Number: A Holocaust Survivor's Autobiography, among many others, use these stark reminders.

Nostalgia makes its presence felt through pictures from a bourgeois urban environment mixed with crowded family photographs from a more traditional village past. On the cover of Gerda Bikales's Through the Valley of the Shadow of Death: A Holocaust Childhood, the young daughter, perhaps 8 years old, stands proudly in a city square, flanked by her seemingly prosperous parents. In the background, a tobacconist's establishment occupies the corner of a building with a Nazi flag hanging ominously at its highest floor.

Some jackets reproduce official documents. Mottled fading notices with characteristic type fonts underscore the relationship between bureaucracy and horror. Passports stand in for their owners to evoke the hardships of the era. Naomi Litvin's We Never Lost Hope: A Holocaust Memoir and Love Story shows a much folded and unfolded, stamped and sealed certification marking a rite of passage from captivity to freedom.

Many of the memoirs exhibit a lone picture of the memoirist on the cover, capturing a moment of loss or achievement, recuperation or dismay. Among these are Alicia Nitecki's Jakub's World: A Boy's Story of Loss and Survival in the Holocaust, Shlomo Waks' Shlomo: The Holocaust Story of an Optimist, and Laszlo Berkowits's The Boy Who Lost his Birthday: A Memoir of Loss, Survival, and Triumph.

My own book cover is a kind of mini family album. I sit on my mother's knee in the foreground while on the bottom right is an early 20th-century picture of my father in Vienna, then a child of 3 or 4. He's dressed as a drummer boy in a suit bought for him by his American uncle, Adolph Engelsman. Above the drummer boy is a photo of my mother and father, comfortable on their honeymoon, striding into an unanticipated future. In the upper left is a somewhat looming picture of me at age 26, taken in 1964 in front of the U.S. Supreme Court, where I was clerking for Associate Justice Potter Stewart. This is a combination of the "American Opportunities" and the "Viennese Dreams" of my book's title.

I asked representatives of my publisher, Central European University Press, to let me know who had prepared the cover and what they had had in mind. They answered that the dust jacket was designed by Sebastian Stachowski, who managed the typography, and Malgorzata Boszulak, who was in charge of the graphic design. They understood, I was told, that the composition of the cover, including its fonts and colors, provide the reader with the first clue, the first sense of the book's emotional context. I had sent many images, each telling a different story, and these were the ones selected. And Boszulak had chosen soft, pastel colors as a way of conveying a tone.

My book cover touches on many of the conventional chords of Holocaust memoirs, but skirts others. It stops short, as does my book itself, of the explicit markers of extermination and horror -- markers I suffered only at the margin. I never thought of myself as a "survivor," and the cover reflects that fact.