I wasn't exactly surprised when the email came from Joyce and Kevin Lucey. They've been sending emails like this for years, recounting what the Veterans Administration is -- and, more often, isn't -- doing to help veterans flailing about in search of care.

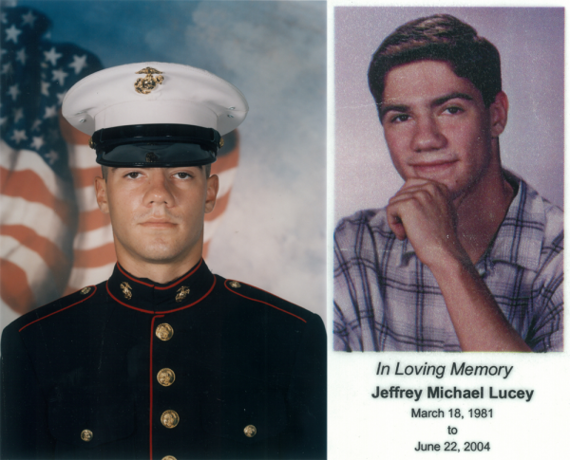

This one begins, "We would encourage anyone to go to the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of the Inspector General site; look for Review of Quality of Care Involving a Patient Suicide; look for Report # 05-02562-124." So I go and I look, and although the subject of the report is anonymous, it's clearly their son Jeffrey, who was a 23-year-old corporal in the Marine Reserves when he hanged himself from a rafter in the family's basement in June 2004.

What occasioned this email is last week's Senate hearing about charges that waits for care at VA hospitals and clinics are interminable unto dangerous. The outrage de jour is the allegation that some 40 veterans died as a result of delays at the VA facility in Phoenix, which seems to have cooked the books to cover up its backlog. VA Secretary Eric Shinseki declared he is "mad as hell" about the situation, the President is even madder, and heads have begun to roll - though if heads can slither away, that may be a more accurate description. To the Luceys, however, it's just more of the same.

Referring to John Boehner's comment that problems at the VA are "systemic," their email concludes, "Read [the report] ... and see if issues existed back then. Mr. Speaker was right...so over the past 9 years why didn't anyone correct them? Why did 'the system' allow so many to continue to die?"

The Luceys live in a small town in western Massachusetts. Kevin, a big man with a soft, jowly, expressive face, is a therapist for sex offenders. Joyce, who wears Jeffrey's dog tags around her neck, was a nurse until suffering a stroke shortly before her son's return from Iraq. With their plain-folks manner, mournful story, and eagerness to inform, they became the go-to family for anyone reporting on military suicide and their story has been burnished with many retellings.

Jeffrey Lucey was part of the initial invasion of Iraq and served as a convoy driver there for four months. Like his parents, he had opposed the war, but, like most marines, when he was called up, he went. Home by July 2003, he was discharged from active duty and joined the reserves. He seemed okay at first, but soon, he began drinking heavily, sleeping badly, acting erratically, and raging at himself for what he had seen and done. "He was slowly dying in front of our eyes and nobody knew what to do," Joyce said.

Despite his symptoms of PTSD and an inability to function, it was VA's policy to withhold help until he was alcohol-free, and when he resisted staying in the hospital, he was sent home with only spotty follow-up. Jeffrey didn't want the Marines to know what was happening because he didn't want the stigma of a psychiatric discharge. So the story of his decline continues, from his family's repeated pleas to the VA for help, to a car crash, which may have been a suicide attempt, to his request to crawl onto his father's lap the night before he died.

It's heartbreaking and it's not unusual.

When Jeffrey killed himself, military suicide was barely mentioned, but as suicide among active-duty personnel climbed toward its peak of 343 in 2012, it couldn't be ignored. The 2013 statistics, released last month, show a significant decrease since then -- 16 to 18 percent, depending on which numbers you use - but the incidence is still alarming, as is the news that suicides among the Army National Guard and Reserve have increased. (Statistics about suicide among veterans are woefully inadequate, but an oft-cited estimate is 22 a day.)

The Army believes measures it instituted have helped, and fingers crossed that's true. (This despite some dubious approaches, such as the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program, a $125 million, five-year program based on the theory that building emotional, mental, and spiritual resilience in soldiers before they go to war will protect them against the psychic and moral consequences of being in war.)

More promising is the Army's 24-hour suicide prevention hotline, but most soldiers and marines still view psychiatric problems as weakness, and the military still doesn't count suicides as casualties of war. Joyce Lucey argues, "If [officials] don't recognize suicide, then how do you expect to get rid of a stigma that comes from boot camp right up the ranks?"

Report # 05-02562-124 was largely protective of the VA, but it did acknowledge some deficiencies in the response to Jeffrey's distress and that bolstered the Luceys' case when they brought the first wrongful death lawsuit of its kind against the Veterans Administration. In a significant victory for them and, they hoped, for other distraught and ill veterans, the Justice Department determined in 2009 that, although the VA was not responsible for Jeffrey's death, he had received substandard care.

"What is so surprising to us after we were assured of corrective actions," the Luceys write me now, "the continuing failures of the VA show attitudes which are completely incompatible with the mission and the treatment for which the VA was created."

In a statement at the hearing, John McCain intoned, "How we care for those who risked everything for us is the most important test of a nation's character." I'd nominate several other tests as equally important, but for all of our crowd-gone-wild homecomings as some kid in uniform strides onto some ball field to some family's teary surprise, this nation's treatment of its sick and heartsick veterans is yet one more betrayal.

As Joyce once put it to me, "Neither our veterans nor their families should ever have to beg for the care they should be entitled to."