Nathaniel Creager had been firing through three packs of unfiltered Chesterfields every day for about 20 years when the Surgeon General released the landmark Smoking and Health report, the document that scientifically linked cigarettes to cancer, heart disease and more.

Despite the warnings, he kept puffing away for about another decade.

PAD affects more than 200 million people worldwide. The older you are, the higher your risk. Risks are further escalated by tobacco use, diabetes and high cholesterol. People with PAD also are at a higher risk of heart attack or stroke. Yet there's some good news, too -- when caught early, PAD can be managed and treated in ways that also reduces those risks of heart attack and stroke.

Nat's physicians knew how to treat PAD. He lived with it for about 30 years before passing away in 2014 at age 91.

In those added years, Nat saw grandchildren born, grow up and get married. Great-grandchildren arrived. And there were milestones for his own children, such as learning that Mark would become president of my organization, the American Heart Association.

Dr. Creager became our top science volunteer in July. That same month, he left his role as a professor at Harvard Medical School and director of Vascular Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital to become Director of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Heart and Vascular Center, the nonprofit academic health system connected with Dartmouth College's Geisel School of Medicine.

In his yearlong tenure atop the AHA, Dr. Creager is shining a light on the disabling and often fatal conditions of the arteries and veins. This is understandable considering that's his area of expertise.

Yet to Nat Creager's son, it's also personal.

It is my pleasure to turn this spot over to him to continue this important conversation.

***

What if I told you a test could determine whether you're at an elevated risk for heart attack and stroke, and all it would take is removing your shoes and socks for about five minutes.

What if I told you a test could determine whether you're at an elevated risk for heart attack and stroke, and all it would take is removing your shoes and socks for about five minutes.

Surely, you'd be eager to do that. And you'd like to think that all healthcare providers would gladly spare those five minutes, especially since the test can be handled by the same assistant who already performs pulse and blood pressure checks.

In fact, that's all the test is -- taking pulse and blood pressure readings around a patient's ankle in addition to doing so at the traditional spots.

We check pulse rates at the neck or wrist and blood pressure at the biceps because those points are close to the heart. By also taking those measurements all the way down at your ankle, and then comparing the numbers, we get a snapshot of how well your circulation is working.

The key metric is your systolic blood pressure, the top number in a blood pressure reading. This is the amount of pressure created when the heart beats and pushes blood through your arteries. If it is lower at the ankle than the arm, that's a good indication of a blockage.

Let me back up and provide some basics about our bodies.

Much like all pipes gather a certain amount of gunk, all sorts of cholesterol and debris gathers in our bloodstreams. This is plaque. A dangerous accumulation of plaque is called atherosclerosis, a term that comes from the Greek words for "hard gruel."

When too much plaque gathers in your heart, it causes a heart attack.

When too much plaque gathers in your brain, it causes a stroke.

And when plaque gathers in your legs, it's PAD.

This blockage prevents adequate nutrition and oxygen from getting to the calf and/or thigh muscles. The more of the bad stuff that's in the way, the less of the good stuff that gets through.

When people with PAD walk, they use up the energy stored in their legs and can't replace it very quickly. This causes pain. It goes away with rest because that gives the good stuff time to replenish.

The blessing-in-disguise element of PAD is that it can be a warning sign. Think of it this way: If you have a buildup of plaque in one part of your vascular system, it's likely to be in others. This is why someone with PAD is at a higher risk of heart attack or stroke.

So, why don't more healthcare providers look for PAD? And why don't more patients know about it?

Those are important questions. And, as AHA president, I've taken a few steps toward answering them.

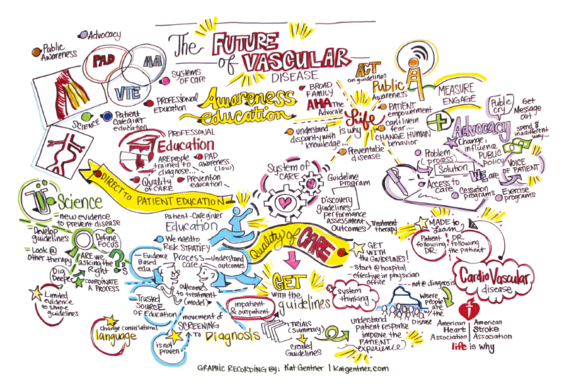

In August, I gathered about 70 thought leaders to map out ways to increase public awareness, patient detection and professional education. In November, those same themes were the crux of my Presidential Address at the AHA's most important scientific gathering of the year, Scientific Sessions.

The challenges are many, starting with the fact that healthcare providers aren't looking for it ... even though AHA treatment guidelines recommend doing it for everyone over 65 and for all over 50 who smoke or have diabetes.

Doctors will not make the diagnosis of PAD if they fail to look for it. They miss an opportunity to detect signs of plaque build-up, atherosclerosis, and begin treatments to prevent future heart attacks. They may mistakenly attribute leg discomfort to arthritis, gout or aging. A miss can be devastating, and some are particularly illustrative.

- I attended a conference where a woman told of her dad's leg pain dismissed as age and arthritis. When his toes turned black, frostbite was blamed. He ended up losing both legs. His amputations would've been very preventable had PAD been diagnosed sooner.

- A former AHA national board chairman who'd had a triple bypass and later received several stents to clear blockages in his heart was having leg pain. His doctors sent him for all sorts of elaborate tests before eventually tracing his problem to PAD. It's also worth noting that despite all his AHA work, he wasn't familiar with PAD or the idea of requesting pulse and BP checks at his ankle.

Even when PAD is diagnosed, we don't always treat it properly. Research shows that less than one-third of PAD patients receive the necessary risk-modifying therapies. This is a shame because it can be easy.

The first step is taking medicine such as aspirin and statins. This again taps into the blessing-in-disguise notion because taking those drugs for PAD also reduces the risk for heart attack or stroke.

Another option in managing PAD is supervised exercise training. This can be as simple as walking on a treadmill.

One of my patients did that for 30 minutes a day over many weeks. She improved so much that she took her 5-year-old granddaughter to Disney World for several days. The woman later wrote me a letter in which she called that trip the most wonderful vacation of her life.

"The joy of seeing her face light up was well worth all the hours I have spent exercising," she wrote. "Thank you for giving me back the will to continue walking."

Not every case can turn out as well as hers, or my dad's. But we can be doing far better than we currently are.

So, remember, the next time you have a checkup, if nobody asks you to take off your shoes and socks, be sure to recommend it.

PAD affects more than 200 million people worldwide. The older you are, the higher your risk. Risks are further escalated by tobacco use, diabetes and high cholesterol. People with PAD also are at a higher risk of heart attack or stroke. Yet there's some good news, too -- when caught early, PAD can be managed and treated in ways that also reduces those risks of heart attack and stroke.

Nat's physicians knew how to treat PAD. He lived with it for about 30 years before passing away in 2014 at age 91.

In those added years, Nat saw grandchildren born, grow up and get married. Great-grandchildren arrived. And there were milestones for his own children, such as learning that Mark would become president of my organization, the American Heart Association.

Dr. Creager became our top science volunteer in July. That same month, he left his role as a professor at Harvard Medical School and director of Vascular Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital to become Director of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Heart and Vascular Center, the nonprofit academic health system connected with Dartmouth College's Geisel School of Medicine.

In his yearlong tenure atop the AHA, Dr. Creager is shining a light on the disabling and often fatal conditions of the arteries and veins. This is understandable considering that's his area of expertise.

Yet to Nat Creager's son, it's also personal.

It is my pleasure to turn this spot over to him to continue this important conversation.

***

What if I told you a test could determine whether you're at an elevated risk for heart attack and stroke, and all it would take is removing your shoes and socks for about five minutes.

What if I told you a test could determine whether you're at an elevated risk for heart attack and stroke, and all it would take is removing your shoes and socks for about five minutes.

Surely, you'd be eager to do that. And you'd like to think that all healthcare providers would gladly spare those five minutes, especially since the test can be handled by the same assistant who already performs pulse and blood pressure checks.

In fact, that's all the test is -- taking pulse and blood pressure readings around a patient's ankle in addition to doing so at the traditional spots.

We check pulse rates at the neck or wrist and blood pressure at the biceps because those points are close to the heart. By also taking those measurements all the way down at your ankle, and then comparing the numbers, we get a snapshot of how well your circulation is working.

The key metric is your systolic blood pressure, the top number in a blood pressure reading. This is the amount of pressure created when the heart beats and pushes blood through your arteries. If it is lower at the ankle than the arm, that's a good indication of a blockage.

Let me back up and provide some basics about our bodies.

Much like all pipes gather a certain amount of gunk, all sorts of cholesterol and debris gathers in our bloodstreams. This is plaque. A dangerous accumulation of plaque is called atherosclerosis, a term that comes from the Greek words for "hard gruel."

When too much plaque gathers in your heart, it causes a heart attack.

When too much plaque gathers in your brain, it causes a stroke.

And when plaque gathers in your legs, it's PAD.

This blockage prevents adequate nutrition and oxygen from getting to the calf and/or thigh muscles. The more of the bad stuff that's in the way, the less of the good stuff that gets through.

When people with PAD walk, they use up the energy stored in their legs and can't replace it very quickly. This causes pain. It goes away with rest because that gives the good stuff time to replenish.

The blessing-in-disguise element of PAD is that it can be a warning sign. Think of it this way: If you have a buildup of plaque in one part of your vascular system, it's likely to be in others. This is why someone with PAD is at a higher risk of heart attack or stroke.

So, why don't more healthcare providers look for PAD? And why don't more patients know about it?

Those are important questions. And, as AHA president, I've taken a few steps toward answering them.

In August, I gathered about 70 thought leaders to map out ways to increase public awareness, patient detection and professional education. In November, those same themes were the crux of my Presidential Address at the AHA's most important scientific gathering of the year, Scientific Sessions.

The challenges are many, starting with the fact that healthcare providers aren't looking for it ... even though AHA treatment guidelines recommend doing it for everyone over 65 and for all over 50 who smoke or have diabetes.

Doctors will not make the diagnosis of PAD if they fail to look for it. They miss an opportunity to detect signs of plaque build-up, atherosclerosis, and begin treatments to prevent future heart attacks. They may mistakenly attribute leg discomfort to arthritis, gout or aging. A miss can be devastating, and some are particularly illustrative.

- I attended a conference where a woman told of her dad's leg pain dismissed as age and arthritis. When his toes turned black, frostbite was blamed. He ended up losing both legs. His amputations would've been very preventable had PAD been diagnosed sooner.

- A former AHA national board chairman who'd had a triple bypass and later received several stents to clear blockages in his heart was having leg pain. His doctors sent him for all sorts of elaborate tests before eventually tracing his problem to PAD. It's also worth noting that despite all his AHA work, he wasn't familiar with PAD or the idea of requesting pulse and BP checks at his ankle.

Even when PAD is diagnosed, we don't always treat it properly. Research shows that less than one-third of PAD patients receive the necessary risk-modifying therapies. This is a shame because it can be easy.

The first step is taking medicine such as aspirin and statins. This again taps into the blessing-in-disguise notion because taking those drugs for PAD also reduces the risk for heart attack or stroke.

Another option in managing PAD is supervised exercise training. This can be as simple as walking on a treadmill.

One of my patients did that for 30 minutes a day over many weeks. She improved so much that she took her 5-year-old granddaughter to Disney World for several days. The woman later wrote me a letter in which she called that trip the most wonderful vacation of her life.

"The joy of seeing her face light up was well worth all the hours I have spent exercising," she wrote. "Thank you for giving me back the will to continue walking."

Not every case can turn out as well as hers, or my dad's. But we can be doing far better than we currently are.

So, remember, the next time you have a checkup, if nobody asks you to take off your shoes and socks, be sure to recommend it.