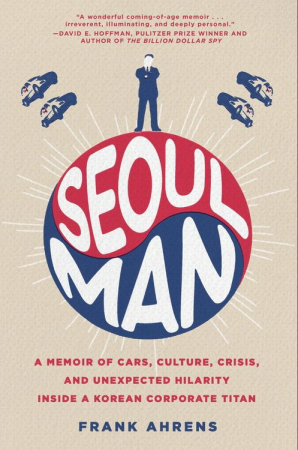

Frank Ahrens' new book Seoul Man is the witty, insightful, and touching story of making the most dramatic changes possible in just about every area of his life all at once.

Frank Ahrens' new book Seoul Man is the witty, insightful, and touching story of making the most dramatic changes possible in just about every area of his life all at once.

Ahrens was an 18-year veteran reporter for the Washington Post who left journalism for in-house public relations at a huge corporation, carmaker Hyundai. He left the US for South Korea. A long-term bachelor, he got married to a US diplomat. He became a Christian. He became a father. He writes about multiple culture clashes.

He learned "a totally different definition of what it meant to be crowded, what it meant to be rude, what it meant to be considerate, what it meant to be a team player." His most fundamental assumptions about behavior and communication were challenged, even about whether to reach for a napkin or ask for it to be passed to him. In an interview, Ahrens talked about what he learned and what he misses.

You write that the cultural contrast between a newspaper and a big corporation was as big as the one between America and Korea. What were some of the assumptions about the workplace you had at the Washington Post that you had to recalibrate for Hyundai?

Journalists, by nature and by profession, tend to be soloists, at least I was. Just ask any editor who's refereed an argument about which reporter's name goes on top of a joint-byline story. Writing a story is a public performance and a journalist enjoys some degree of fame; more in the digital era. Corporations, on the other hand, tend to be team- and division-oriented, and the individual goal is often sublimated to the team and corporate goal. Most corporate employees are unknown outside their firm. After going to work in a corporation, and learning about other corporations, I came to understand that the newsroom culture works upside-down from any other business environment. Example: As a typical corporate employee, you work for the company's best interest. As a reporter who covered The Washington Post Co., I sometimes wrote stories that harmed the company's -- my employer's -- best interest. In any other corporation that would, and should be, a firing offense.

You say that "culture eats strategy for lunch." What does that mean?

It's a play on that great Peter Drucker line, "Culture eats strategy for breakfast." He meant that workplace cultures can be so ingrained, it can be impossible for any new strategy to take hold and overcome them; they are so easily swallowed up by the workplace culture, it's like they were eaten for breakfast. When I suggested Hyundai's (and Korea's) set-in-stone noon lunchtime, which caused massive cafeteria crowding, be staggered across a couple of hours, I was informed that Koreans are so used to eating lunch at noon it could not change. My strategy was eaten for lunch by the culture.

How is Confucianism reflected in the Korean workplace?

In the same way oxygen is reflected in the atmosphere -- infused, inseparable, life-sustaining. Corporations in Korea, or almost anywhere, are hierarchical in nature. In Korea, and elsewhere in East Asia, you layer on another, reinforcing hierarchy -- Confucianism, which demands deference to elders and superiors and devotion to country and company (I found myself Freudian-slipping many times, saying "country" when I meant "company"). It creates a top-down, command-and-control structure generally run by men and "harmony," or what we could call "conformity." This is not, however, to say it is inflexible. Top management at Hyundai and other chaebol will change policy when persuaded by good plans. This is how the Hyundai Veloster got made and the Hyundai Elantra ended up looking as good as it does. Also, "conformity" as a negative concept is a Western construct; it's a mistake to apply it to Eastern cultures in the same way.

You write about a dynastic approach to CEO succession at Hyundai. If the son of the current chairman takes over and then has no children, or has only daughters, what will happen?

First off, it is almost impossible to imagine an heir to a chaebol being childless; duty and love of family make that inconceivable. Up through today, the dynastic daughters typically run the "softer" chaebol businesses, such as hotels and department stores, instead of electronics and automobiles.

Samsung and Hyundai Motor are on the verge of transitioning from their second to third generation leaders. Both third-generation sons speak English and were educated in the West, unlike their fathers. Both have already shown more of a global view than their fathers and further cultural change is expected. Another question you could ask: What happen if the son of a current chairman turns out to be incompetent? This is a potential problem with every family owned business, whether Korean (Hyundai, Samsung), Australian (NewsCorp) or American (New York Times). Dynastic leadership has its upsides -- long-term planning, continuation of culture and core values, brand maintenance -- but can have its downsides if the dynasty produces a sub-par heir. And the male-dominated dynastic hand-down has its critics even among the chaebol; I would not be surprised to see a woman heading one of the smaller chaebol at some point in the not-too-distant future. No one ever thought Korea would elect a woman president.

What is "modern premium" and how is it reflected in the company?

It was the brand philosophy Hyundai came up with to try to convey to consumers what its cars should look and feel like. "Traditional premium" in cars, we felt, implied over-the-top, gaudy, unnecessary gizmos, over-chromed, focused on style over substance, and so on. "Modern premium" meant a car that included the technology people wanted, that was intuitive -- easy to use -- and that created an emotional connection with the consumer. A great example: iPhones. They work out of the box, they're intuitive and they make you feel cool. (By the way, in Korean, "Hyundai" means "modern.")

What did "the napkin episode" teach you about manners?

I learned that here were two cultures -- Korean and American, East and West -- each trying hard to behave in the most polite way possible to each other, only to be acting in the rudest way possible. It taught me that two cultures, two people, can look at the exact same thing and have it mean two completely different things. I wish it had happened to me right after I arrived in Korea instead of right before I left. But, then again, I might not have put two and two together that early in my experience.

How did the drinking culture in business challenge your professionalism?

It challenged both my professionalism and my faith. Biblically, Christians are not forbidden from drinking (see: Last Supper) but they are instructed not to get drunk. In Korea, *the point* of the drinking culture is to get drunk, as a great leveling agent, to create a bond among team members at work and friends out of work. I didn't want to stick out any more that I did at my new job, and I didn't want to offend my new colleagues and country (though I'm sure I did both), but I just wasn't going to drop my principles to fit in. In the end, and with my boss's blessing, I found a middle way: I participated in the important rituals of the drinking dinner, but took only a sip of soju instead of an entire shot during the endless toasts. In terms of professionalism, I had to recalibrate what that word meant in the East Asian business culture, which is more relationship-driven than the Western business culture. No one around me, in their correct-for-their-culture way of thinking, was being unprofessional by drinking so much.

How does the Korean commitment to teamwork over individuality benefit productivity?

There's a standard and truthful answer that this is the duty to one's teammates. It's almost unheard of to see more than a one-week vacation -- and not that common to see even a one-week vacation -- because of the burden you'd place on your teammates who have to carry your load while you're gone. But there's a deeper point here: It doesn't always benefit productivity. If you look at OECD figures, you'll always see Korea at or near the top of the hours-worked rankings. But oddly, Korea will be lower down in the productivity rankings -- however that's determined. That's one thing Korea knows it must, and will, change. Still, too much of what it means to "work" means sitting at your desk where the boss can see you even if you don't have work to do. This is a leftover from the old way of work at Korean -- and probably most other -- corporations. Still, this commitment can be a powerful force when applied to an important deadline project -- you get thousands of people pointed in the same direction all rowing the same way. Really fast.

How is competitiveness expressed in a conformist culture?

This is a great question. It seems like a paradox, right? It was for me until almost the time I left Korea. Finally, it was explained to me by a kind Korean friend. How can a culture that is so competitive when it comes to everything -- school tests, working hours, golf, drinking -- be so conformist to the Western eye? In my culture, I told my Korean friend, the whole point of competition is to stand out from the crowd. He said: In the Korean culture, because everyone is competing all the time, you compete to *fit into* the crowd.

Why do the Korean Hyundais have shiny black center consoles but the American ones have a matte finish?

My surmise: Because Koreans value their mealtimes with their families, team members and friends and don't eat in their cars like Americans. The car I had in Korea, the large Hyundai sedan called Grandeur, had a shiny black plastic center console. The finish is called "piano black" in the industry. The first Grandeurs (badged Azera) sold in the States had the shiny black console, but it showed smudgy fingerprints. So subsequent Azeras had matte (not shiny) consoles, which don't show smudges so badly. You may ask: Don't Koreans have smudgy fingers? I would answer: Koreans don't eat in their cars -- they eat breakfast at home with their families, lunch with their team members at work, and dinner with business clients or fellow executives, all part of the group bonding -- and Americans have made an art form of dining while driving.

What do you miss most about Korea?

I miss the friendships I made with my Korean colleagues who took special pains to help this fish out of water. I miss the uniqueness of the place, in its enlightening and even infuriating ways. I miss the feeling of being in a country that felt like it was still striving instead of sailing at cruising speed.