Click here to watch the TEDTalk that inspired this post.

Today, we live in a world where our identities are defined by a collection of our posts, comments, and photos. Advertisers and marketers analyze this content to make predictions about us, gleaning hidden details from the hints we leave behind. In fact, Facebook opened labs this past year to surface more information from our data. However, most of us would argue that our online identities are not who we really are. Rather, it's the mask we have to wear in today's social Internet.

My team in Berkeley wondered how many people knew they live a double life on online networks. The idea though was not so simple so we wondered if we could produce an engaging visualization that demonstrated the concept. For the last few years, my team had been building tools to predict the impacts of political decisions so we had a knack for making interesting web visuals.

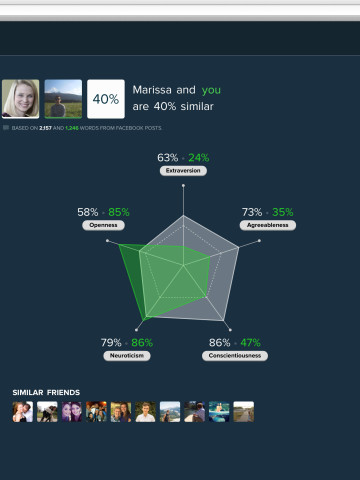

After a few weeks of tinkering with ideas, we came up with a novel concept called Five Labs that predicts your personality based on your Facebook posts, utilizing a language analysis method designed at the University of Pennsylvania. When we launched, our application saw a flood of interest. Publications from The New York Times to The Economist wrote pieces on it. By the first week, we had analyzed over 200 million personalities.

Although many of the app's predictions mirrored people's own self-images, one of the broadest sentiments was that we captured something very interesting: the discrepancy between a person's online identity and their real-life identity.

However, this discrepancy has been fueled by more than just our concerns about how an employer or family member might perceive us online. There's a much more fundamental reason for us creating this false identity: when we broadcast on social media, we don't know who's listening.

Because of this, we're not able to tailor our message for specific contexts like we do in person. For instance, a dinner table conversation with our parents will invariably be different than one with our college roommates. So instead, we construct vanilla profiles, focused on announcements that generally make us look good. And thus, Facebook is now less of a place to socialize and more of a repository of how we would all like to be perceived: our own individually-authored Wikipedia profiles if you will.

Most people forget but Facebook was a much different place in the early days. Connecting people in context was the main value to its users. Your posts were visible by only those in your college network--people of your age, who spoke your language and understood your struggles.

This spawned an intimacy that made many of us fall in love with the network. You could have unfiltered and serendipitous conversations with your friends and acquaintances--whether about politics, music, or just shooting the breeze. It felt like real-life. You could almost say it was like an Internet house party, a term I'm borrowing from technologist Josh Miller.

As the network absorbed new demographics outside of college campuses, the original privacy model that it operated under faded. As a quick bandaid, Facebook adopted arcane privacy-filters that were so detached from our existing patterns of communication that few knew how to use them. Thus, without knowing who might be listening to us, most of us just ended up keeping quiet.

It's starting to become clear that it may not be possible to return to the rich network we saw in the early days, if Facebook is in the driver seat. For better or for worse, many young people have resorted to photo-centric networks like SnapChat and Instagram, where the users are largely their own peer groups. Context on these networks was not part of the product's original aim; it was largely a side-effect since new social technology is adopted by young people first anyway. So as the next wave of adoption comes from older demographics, it is possible that we'll see these networks get displaced as well.

As vapid as social networks might seem to outsiders, communication is vitally important to our lives. It helps us feel connected and it can create real value for society. Mobile phones, after all, have substantially reduced poverty across Africa.

Over the last year, my team has been focused on creating a network of private conversations called Five. It will allow us to engage online in an intimate setting like we did in Facebook's heyday.

Perhaps with Five, we might be able to take off the mask we've all been wearing for the past few years.

We want to know what you think. Join the discussion by posting a comment below or tweeting #TEDWeekends. Interested in blogging for a future edition of TED Weekends? Email us at tedweekends@huffingtonpost.com.