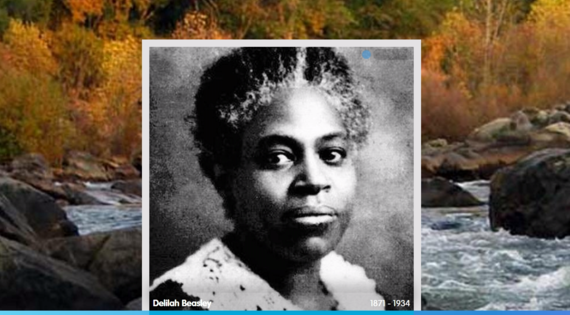

Delilah Beasley was the first African American woman to write a regular column in a major daily newspaper. In addition, she was a fighter against lynching and a historian who brought to life the contributions of her people in California history, bringing them from obscurity to their rightful place.

ORPHANED as a teenager, her gift with words took her on a journey from her roots in Cincinnati to writing about the roots of her African American brothers and sisters all across California, uncovering prejudice and neglect, and yet always persevering.

She never hesitated to raise her voice in the face of injustice, whether against women or African Americans.

And when her life's path came to an end, a community rose in unison to mourn her loss, pledging to continue her struggle to promote brotherhood and understanding. At her memorial service, mourners rose to make this pledge:

"Every life casts it shadow. My life plus others make power to move the world. I therefore pledge my life to the living work of brotherhood and material understanding between the races."

She began her column in the Oakland Tribune, "Events Among Negroes," in 1925. She made a name for herself as a meticulous journalist while covering events in the African American community.

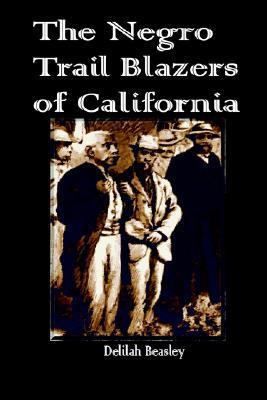

In addition to her newspaper work by day, she found time by night to write her highly regarded books on California history in a university library, including her seminal "The Negro Trail Blazers of California" and "Slavery in California: A Journal of Negro History."

Her journalism could be mundane at times, writing about daily events at churches, presentations at schools and other community events.

But she could wield a cudgel as well.

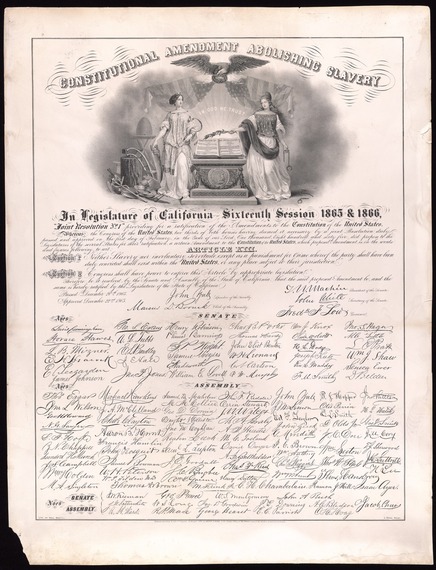

Her editorial influence led to the first anti-lynching law in California, a practice that was used at the time primarily against Hispanics, Asians and Native Americans.

She used her column to oppose the overt racism of D.W. Griffith's 1915 silent film, "Birth of a Nation," which glorified the Ku Klux Klan. She campaigned against the use of derogatory words describing African Americans in newspapers, and published articles on the achievements of Black men and women.

Far from being strident, she was known for building support among whites for causes within her own community.

"If a bit of news would have the tendency of bettering our position in the community," she once said, "then it should be published not only in our own race papers but in the papers of the other race as well."

Beasley, who died on August 18, 1934, or 82 years ago this week, is celebrated annually by the African American Quilt Guild of Oakland in a display of quilts paying homage to California and African American history. One quilt depicts Beasley, one of the state's great story tellers, against a colorful backdrop that includes photos of African American heroes.

Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, she was the oldest of five children. But with the death of her parents while she was a teenager, she had to find a way to support herself. She studied to be a masseuse, but soon found work writing for a Black newspaper, "The Cleveland Gazette," where she mostly wrote about church events and social activities.

She published her first column in 1886 in "The Cincinnati Enquirer," with the column heading, "Mosaics."

In 1910 she moved to Oakland at the age of 39 and wrote a column for a Black community newspaper called "The Oakland Sunshine." During that period, she began researching the lives of African American pioneers at Bancroft Library at the University of California-Berkeley.

At the time, African Americans were thought to have played a negligible role in the state's history. She proved otherwise.

Following nine years of research, she published her first book in 1918, "Slavery in California, a Journal of Negro History." In the book she noted that Mexico had outlawed slavery long before California was annexed by the United States, only to have the sordid practice re-introduced.

"At the time the United States government acquired the territory of California from Mexico, slavery had been abolished there nearly twenty years," she wrote.

She sought to demonstrate to the newspaper readership that Blacks had, indeed, played a major role in the state's development. Women played a prominent role in her histories.

The following year, she published "The Negro Trail-Blazers of California," describing heroes, role models and ordinary citizens who made significant and positive impacts on California history.

As an example, Beasley reported on a Black gold miner in the late 1840s:

"A history of the Negro people of California would be incomplete without mention of the mining men who came in 1849. There were at one time several hundred Negro miners working claims on Mormon and Mokelumne Hill, at Placerville, Grass Valley and elsewhere in California mountains.

"One such man was Moses Rodgers a mining expert who was considered one of the best mining engineers in the state. He was also a metallurgist and owned a group of mines at Hornitus.

"The colored miners rarely took a chance in buying mining stock. He had more sacred duties to perform with his money. He either used it to pay for the freedom or liberty of himself, his family or other loved ones in faraway "Dixie-Land". If not that, then he contributed largely from his diggings to assisting the "Executive Committee of the Colored Convention" in their struggles to secure legislative enactments in the interest of the Negro race in California."- "The Negro Trail Blazers of California," 1919

One prominent cause in which she wielded both her personal and professional influence involved the building of an International House for foreign students at UC-Berkeley, where she was studying. Berkeley denizens opposed the on-campus building, fearing they would be overrun by minorities.

"More than 800 people gathered in Berkeley to protest racial integration in the proposed International House," reported the university newspaper. "At that meeting, Delilah Beasley, a black reporter for the Oakland Tribune, passionately defended the concept to a disgruntled and stunned audience. And it was Beasley who stood up to the protests of property owners who feared that I-House would cause Berkeley to be overrun with Blacks and Asians."

Notable residents of the international center eventually included Delbert E. Wong, the first Chinese American judge in U.S. history, Governor Jerry Brown, and State Supreme Court Justice Rose Bird.

To date, six books and innumerable articles have been written about Beasley, though her impact is little known outside California. Biographer Lorraine J. Crouchett, describes her as follows:

"Beasley found that Black Californians had no history; their records had been discarded from the collections that documented the state's development. Yet in reproducing the words and photographs cherished by individuals, she caught their humanity as no one before her had done. "

Record your own family history for free at OurPaths.com.

Sources:

- National Women's History Project

- Oakland Tribune

- African American Quilt Guild of Oakland

- Blackpast.org

- Oaklandlibrary.org

- California Historical Society

- Wikipedia.org