I am one of the legion of Sylvia Plath-Ted Hughes acolytes who populates the fringes of literary history.

Like many young women, I found The Bell Jar, written by Plath, to be the first novel that dared broach subjects I was wrestling with myself. After at least a half dozen or more readings, its clear-eyed view of life is still contemporary.

Plath's poetry was deep and thorny and took more digestion; I came to love it and understand it better as I grew older, even though she wrote some of it when she was in her thirties. She died, as everyone knows, by sticking her head in the oven with her children upstairs -- a victim of depression, yes, but also devastation that the love of her life, Ted Hughes, had met someone else. In the weeks up to her suicide she was still reading the Art of Loving to try to understand the disintegration of her marriage.

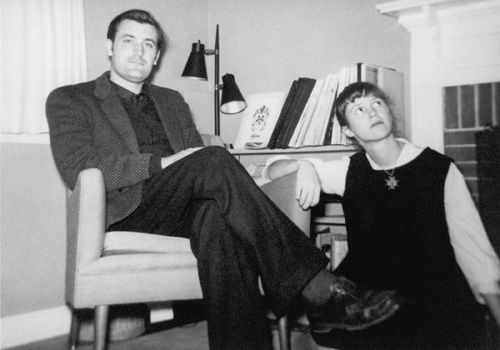

Ted Hughes and a pregnant Sylvia Plath.Sylvia Plath Collection, Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College. Photograph by Marcia Brown Stern © Marcia B. Stern

For a while, I lined up with those who thought Hughes a cold-hearted bastard.

Then, I began reading his poetry, sometimes more challenging, as his points of reference were often beyond my ken (references to other literature abound), but like hers, so sumptuously laden with potent images as to be breathtaking.

Then he released Birthday Letters , the book of poems which finally spilled some of the tortured beans he had been forced to carry silently, both for the sake of his children, Nicholas and Frieda, and out of deference to his own mental health.

I have read all of the individual biographies and one that explored their relationship together and apart. Then in 2005 I went to a heartbreaking exhibition at the Grolier Club in New York, drawn from their respective collections at Smith and Emory which charted their lives in letters and photographs. I stood in front of the vitrines -- by then I understood about love and loss -- and absent the ability to actually handle the materials myself, was able to channel something of this historic couple.

Though Hughes did not ask it of me, I forgave him. I saw that Plath was as difficult and challenging a love partner as Hughes and that as they say, nobody ever knows what goes behind the closed doors of a marriage.

Finally, just a few months ago, I spent night after night reading the first volume of his letters that has been issued. I was absolutely entranced: Hughes was not only a brilliant correspondent, but herein was finally revealed some, if not all, of his agony as he separated from Plath, after her suicide and his herculean effort to shield the children.

About marriage, he had this to say:

"Marriage is a nest of small scorpions but it kills the big dragons."

And about literary life:

"Literary Life is more exhausting nervously, than most, because it works with nothing definite or regular, it is a continuous improvisation of reality out of illusions and fantasy, without set limit or hours. One needs to provide substance and duties to the life."

There are tortured letters to Plath's mother about her wanting to visit the children in England after Plath's death, and Hughes resisting, always attempting to shield the children not only from public scrutiny but also from the private check-ups of the family.

But the letters which touched my heart most deeply (as I am now a parent) were the ones to Nicholas as he grew old enough to understand something of what had happened when he was so very young. Hughes traveled delicately through the minefield of his marriage to Plath and shared finally with Nicholas the agony of protecting him from the demons of his own mother -- as much as he wanted him to know and revere her.

When Nicholas was born in 1962 Plath wrote, "Nicholas is a true Hughes, craggy, dark, quiet and smiley."

When I heard the news of Nicholas's suicide this week in Alaska, I could not have been more devastated if he had been a son of my own. Here was proof positive that we cannot separate our children from our own action, or inaction, and that no matter what we tell ourselves, the bonds, and inheritances of family run deep and twisted. I was relieved to hear he had a girlfriend, and that he had once found some measure of solace in Alaska and its natural world, about as far away from literary London as can be imagined. It is said by a family friend that it was when Hughes died that Nicholas's fragile spirit was then, finally, undone as his lifetime protector was no more.

In about 1968 in his notebook, Hughes recorded the following dream:

"As if... Sylvia had been brought back to life. The great hope was that she could see the children... she met all her friends, etc. in the States and had a whole day and night with Frieda and Nick."

I don't usually believe in the afterlife, but in this case I very much want to: I imagine the reunion of the mother and the son she had barely known, and the father who could not protect either of them. I hope they are sitting around and getting to know each other.