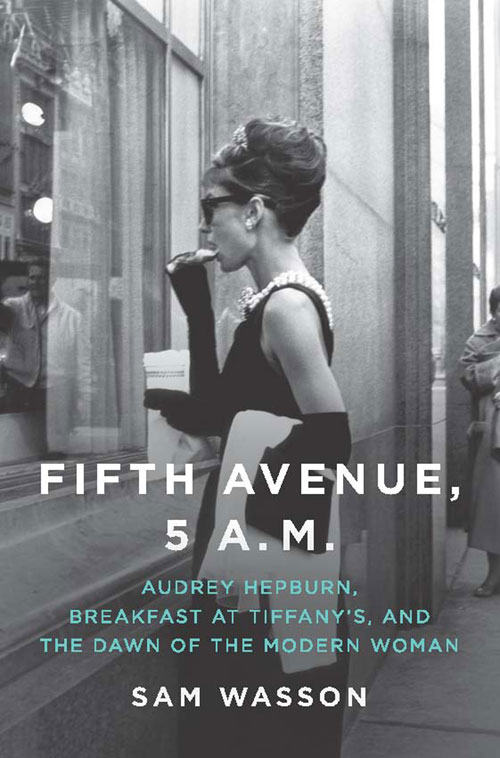

Each time I put on a black dress, I am convinced that if I elongate my neck just...so...and put my hair up just... so... and perch the sunglasses just... so... and the kitten heeled slingbacks just... so... and do the pearl clasp just... so... and spray on my vintage L'Interdit just... so... I might have purchase on Audrey Hepburn's Holly Golightly from Breakfast at Tiffany's. Truth be told, there is probably not one woman alive of any age who does not hope against hope that her left clavicle could contain even a soupcon of Hepburn on Fifth Avenue, 5 am in 1960.

Roger Corman, the lifelong professional Hollywood skeptic, asked me, "How can you say anything new about Breakfast at Tiffany's?" But Sam Wasson has proven he can in his small-sized but big-hearted and original book that tells how they captured Hepburn's magic.

Oh, she had lots of help, of course. A feisty director, two eager producers, a costume designer, a fashion designer, a tunesmith and his lyricist, a cinematographer, and more. Wasson regales us with facts and a little recreated fiction drawn entirely from rigorously sourced first person material.

And personally, I don't care if they all actually said those precise words or not. I was so happy to be a fly on the wall of the gestation of this film, which like other films I've been writing about this year, tells the tale of a very modern, ahead-of-her-times woman and the damage she inflicts. Wasson has demystified her, but not too much -- if we can't fantasize about being Holly any more, then what's the point?

I don't actually agree with Wasson that Hepburn was the dawn of the new woman, as she followed hard on the ballet flats of Patricia in Breathless (1960) and other films of the New Wave. But the hyperbole is close to right -- she was just as much one of the Women of the Wave, as I have dubbed them, a wave that broke first on the shores of France and then cascaded to England and the US in no time at all. So she was certainly the Dawn of the American Woman and lord knows, after all those years of Doris and Marilyn, we were ripe for something new. It turned out to be Hepburn, she of the flat chest and the hybrid upperclass accent that came along just at the right moment, not quite as deadly as Patricia in Breathless, or Catherine in Jules and Jim , but sharing with those diaboliques certain attributes: beautiful but not perfect, independent but damaged, sexual and needy but unwilling to pay the price of permanent connection.

But short of trying to smell like Hepburn and look like her, could you actually be like her? What was it that made her get under our skin? Capote's original novel had more of the dark; the film softened Holly up a bit: a fun girl, not a call girl, a damaged Texas child bride who needed petting and affection, just like a kitty cat. This vulnerable, kitten-y waif, washed up on the shores of the Upper East Side, was so original, such a pleasure to behold, that to aspire to being Holly has never gotten old.

Sam Wasson took a minute away from working on his next book (about Bob Fosse) to go Off the C(H)uff with me. We examined the mysterious alchemy that made Hepburn's Holly into the icon she is today.

SW: In short, all of them - and more. Capote (obviously), Audrey, Axelrod (for the reasons you mention), Givenchy (for imbuing Holly with that aura of experience and sophistication), Blake Edwards (for fighting any number of fights to make sure that all around him could do the work they did), Henry Mancini (for reminding us, through "Moon River," just who she was on the inside), and the producers, Richard Shepherd and Marty Jurow (who thought it would be a good idea to make a movie of "Breakfast at Tiffany's" when no one else did). There is no single auteur responsible here. Making Holly Golightly into the girl that exists up there on the screen was a synergistic process, a fusion of likeminded (and sometimes divergent) individuals who by some strange process of fortitude, good luck, and original vision, managed to, all at once, pour themselves into Audrey Hepburn. Out came Holly.

CZ: Truman Capote took as his many role models for Holly a number of wealthy or privileged young women (Gloria Vanderbilt, Babe Paley, Carol Marcus) as well as some more anonymous candidates. But you seem to also suggest the screenwriter George Axelrod has not been given his due as changing her from call girl to fun girl and imparting a certain warmth and honesty to her persona. And then there is the profound influence of Hubert de Givenchy. Who is really responsible for Holly Golightly?

CZ: You point out that beginning in the sixties, women found that Audrey's character Holly was someone they wanted to emulate. Can young woman today still find something to connect with in Breakfast at Tiffany's even as the notion of sexual freedom is not as much of an issue? SW: Absolutely. Sexual freedom may be licked, at least for now, but there are any number of issues out there that women in the movies will continue to grapple with. For example, Sex and the City, back when it was relevant, dealt with that post-freedom question. How much of a single life does a woman want? In that sense, it's a nice bookend for some of what Breakfast at Tiffany's contends with. But as for young women today, as in right this very moment, I'm a little worried. Many people before me have said what I'm about to say, but it's so important it's worth saying again, even if it's old news: as long as Hollywood is turning out inane roles for young women (see most any of today's romantic comedies), it's going to be hard to see any issues portrayed with any kind of serious consideration. Hollywood is not interested in the way we live now, they way it was, say, when Paul Mazursky made An Unmarried Woman. Accordingly, it's going to be difficult - whether you're a young woman, young man, old woman, or old man - to find something to connect with. CZ: You take pains to document that there was a disconnect between Hepburn's personal life, where she was tethered to the notion of being a good wife and mother -- which meant catering to her husband and children (helped, of course, by her husband Mel Ferrer's domineering ways) and the role of this free spirit in B at T. She does divorce Ferrer eventually and then take up with Albert Finney. Was this film then also the beginning of a new freedom in her personal life and is it a case, then, of life imitating art? SW: You mean Two for the Road? Yes, I think so. Audrey Hepburn reached a new phase, emotionally and artistically, on that picture. But I'm certain she was largely unchanged by Breakfast at Tiffany's. As an actress, her confidence stabilized somewhat, but there were no great breakthroughs for her personally, or conceptually. No one involved in the making of the picture, except maybe Axelrod, intended it to advance the trajectory of women in the movies. They just did what they had to do. And out came a revolution.

CZ: Your end notes show how carefully researched and meticulous you tried to be in hewing to the truth. Yet you fall back on a neo-documentary style of recreations in the text which you acknowledge to be partial conjecture. Why? SW: History is conjecture, and all retelling of it a recreation. When writing about the past - especially a past that you didn't witness firsthand - there are bound to be gaps in understanding. It's the Rashomon thing. I merely wanted to show the reader how I did it, that it took a considerable amount of research and a considerable amount of interpretation to connect the dots, like Tim Curry in that bravura last scene in Clue, when he's running around the mansion explaining how all the murders happened. In that sense, Fifth Avenue, 5 AM is no different than any other serious work of historical non-fiction. And I don't consider that to be a "falling back" nor so I think of it as "neo-documentary" technique. Every biographer, or as I said, historian, has to endeavor the very same thing. I simply wanted to take you behind the scenes of how I took you behind the scenes.

CZ: How is it that you are so smart about women, and get under their skin, at the age of 28? Is Holly the kind of girl-woman you would want to date, or is there too much potential for heartbreak? SW: Am I smart about women? Thank you! Though I'm not sure my girlfriend would agree with you. But what does she know? Holly is not the kind of woman I would like to date any longer than a night or two (but what a night [or two] they would be!) Audrey was never my dream girl. Obviously, I have enormous respect for her, and I'm fascinated by her work, and I'm not sure a human being could really every get any lovelier, but if you want to know my type, I must admit I like them a little saucier, and a little sillier like Emma Stone. Do you know her? She knocks my socks clear off my feet.

You can order Fifth Avenue, 5 AM: Audrey Hepburn, Breakfast at Tiffany's and the Dawn of the Modern Woman the DVD or the original Capote book. All three would make someone a fantastic present. That or the little black dress.