The photographs out of Ferguson are new, but the scene is all too familiar: signs, bullhorns, protesters, police. The ongoing demonstrations in Missouri are only the most recent in a long history of American protests. Groups across the political spectrum have used rallies, marches, and picket lines to bring their agendas to the attention of the media, government and fellow citizens. But public attitudes about this form of political engagement have historically been mixed at best. From the Roper Center for Public Opinion Archives:

Different movements, different attitudes

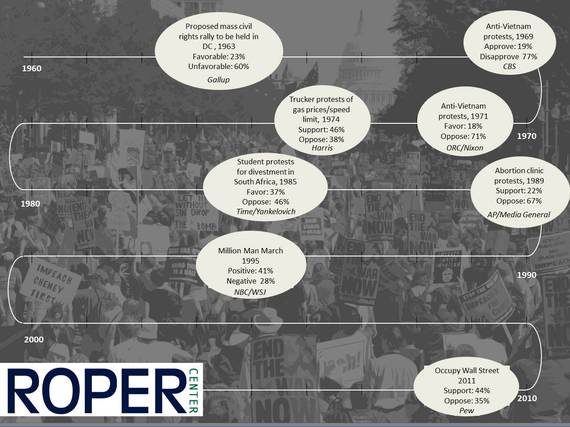

Few generalizations can be made about the public's support for protest movements in general; level of support varies by issue. But perhaps because personal experience with protest is rare -- just 10 percent said they had ever participated in a protest in a 2013 AP/Gfk Knowledge Networks poll -- the public's overall attitude toward mass demonstrations seems to range from skepticism to outright condemnation. Even the most popular protest events have support levels that hover below half, and positive responses are rarely higher than negative ones.

The public is particularly uncomfortable with protest during wartime. The flip side of the "rally-round-the-flag" effect, which unites Americans in opposition to an external threat, is less tolerance for internal dissent. Thirty-one percent in a 2003 Freedom Forum/American Journalism Review poll believed that individuals should not be allowed to protest during a time of active military combat. Similarly, 34 percent in a 1991 LA Times poll thought that protests against the Gulf War were inappropriate once forces were in combat. In a 1970 Harris poll, 37 percent said antiwar protests should be made illegal.

However, Americans can be quite supportive of protests on other shores, particularly in countries where the government is seen as particularly repressive. In a 1979 Carnegie Endowment for Peace/Response Analysis poll, 79 percent said they thought blacks in South Africa were justified in conducting boycotts, sit-ins, and demonstrations in order to improve their situation. A 1989 Harris poll found nine in ten thought the students in Tiananmen Square were right in their demands. Eighty-two percent in a 2011 Gallup poll said they were sympathetic to those protesting for a change of government in Egypt.

Protest movements look better in hindsight

Distance of time as well as place can make protest movements more appealing to the public. In a 1994 Scripps Howard News Service/Ohio University poll, 79 percent of Americans considered Martin Luther King a hero. But a 1966 Harris survey of whites found that 50 percent believed King was hurting the "Negro cause of civil rights," while only 36 percent thought he was helping it. At the time of the civil rights march on Washington where King gave the famous Dream speech, only 16 percent in a national Gallup poll said they had a favorable opinion of the planned protest. Over four in 10 had an unfavorable opinion.

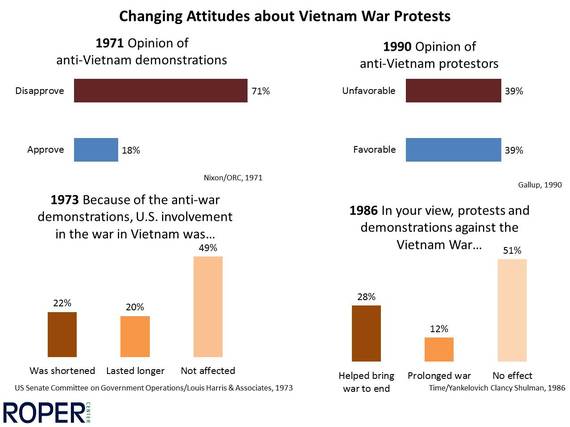

The protests against US involvement in Vietnam were also seen negatively by the vast majority of Americans at the time. A series of polls in the spring of 1971 conducted by Opinion Research Corporation for President Nixon found support for antiwar demonstrations in Washington ranging from 30 percent while the protests were in the planning stages to 18 percent during the event, with between 64percent and 71 percent disapproving. However, polls conducted in the '80s and '90s found the public evenly split in their opinion about anti-Vietnam protestors. The war's dismal ending may have led some to regard the protestors as correct in retrospect, or perhaps the angry students seemed less threatening once they had traded their torn jeans and slogan t-shirts for business suits.

Police and protest

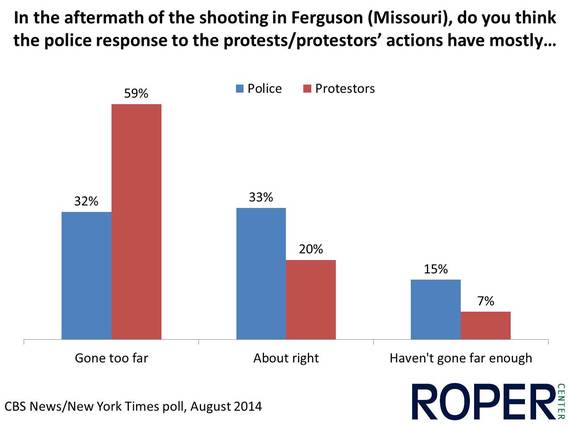

Because mass demonstrations involve disruption and carry the potential for violence, they often are accompanied by a significant police presence. When asked, majorities have supported law enforcement activities in dealing with protestors. Fifty-six percent approved of the way Chicago police dealt with young protestors at the 1968 Democratic convention. Just under a third disapproved. The 1971 OCR/Nixon poll asked what police should do if Vietnam Veterans Against the War refused to leave the Washington Mall, where they had been forbidden by court order to camp overnight. Nearly half thought protestors should be arrested, 37 percent thought they should not. An August CBS News/New York Times poll about Ferguson found more of the public thought the protestors themselves had gone too far than thought the police had.

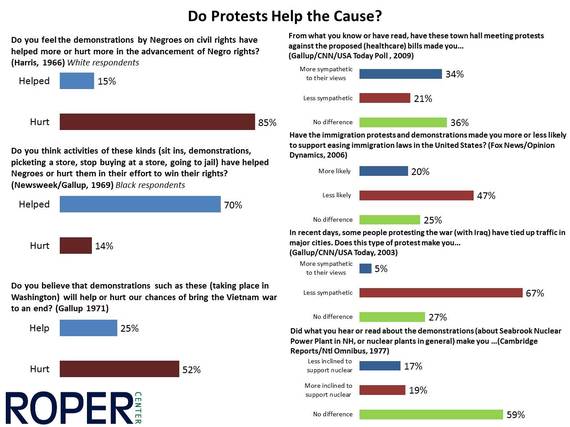

Despite the demonstrable successes of the Civil Rights movement only a decade before, 1976 Gallup poll found that the public was skeptical that protests could bring about change. Just 6% thought protests were very effective in influencing how our government is run and what laws are passed, and 22 percent thought they were fairly effective. But the public's perception of whether a particular protest is likely to help the cause it champions varies considerably by attitudes toward the issue overall. During the civil rights movement, blacks thought demonstrations helped the cause, while whites thought they hurt it. Only 29 percent of the public in a 2003 Gallup poll said they agreed with the views of those protesting the Iraq War, so it is unsurprising that very few (5 percent) said the protests made them more sympathetic. On the other hand, over a third of the public said the 2009 town hall meeting protests against the controversial health care bill made them more sympathetic to the protestors' views.