I had three very timely awakenings at this year's Outsider Art Fair, sponsored by the Museum of American Folk Art, in Chelsea, for five days ending on May 11. They were stunning, shaking me all over, and ultimately beautiful.

The first is that our understanding of Henry Darger, who has become not only the face and star of outsider art, but also a shamanistic ghost-figure of human society, has only begun. I went through a Darger obsession almost a decade ago after seeing In the Realm of the Unreal, the popular documentary about Darger that later played on PBS. I thought I couldn't get enough of him -- I wanted to plunge head first into him, as thousands of people have, then I came up for air. I'd had enough. I couldn't take anymore: the strange, deadpan, foreboding flatness of his world, the "weird" little girls with penises no one could understand, the putative sickness of his mind -- who was this sicko creep with his twisted pursuit of little girls?

I stopped constantly dreaming in Darger.

Then late last year I read Jim Elledge's wonderful biography Henry Darger, Throwaway Boy: The Tragic Life of an Outsider Artist (Overlook Press, 2013) that put everything into place finally. The one word that could not be used about Darger surfaced at last: he was gay. The girls with penises were not girls at all, but tormented boys from the turn of the American twentieth century who, being vulnerable to the abuse of the world around them -- the violent streets, filthy garrets, dark stairs and closets of Chicago's slums; the asylums and orphanages into which boys like 12-year-old Henry were thrown, to be scalded, whipped, choked, and constantly sexually abused, a world of Dickensian depravity -- had to become girls inside. They could not exist within the normal roles of boys. Darger was queer; a piece of that amazing river of consciousness we are finally starting to navigate openly that has been hidden for so long and which finds so many of its wellsprings in childhood itself.

It's quite a river, and we are starting to see other artists there as well: Maurice Sendak for one. Here the wild things are not only in exquisite bondage to sex, but rip it open and go beyond it, finally reaching those innocent shores of transcendent becoming that all human beings yearn for.

As James Brett, director of London's Museum of Everything said to me prior to a panel he was on about Darger, on the tented rooftop at the Outsider Art Fair: "Darger is about the loss of innocence that we can all relate to. That is why we become the way we do about him."

The Darger panel which commemorated this completely unknown artist's explosive entry into the art world 37 years ago, when "The Realms of the Unreal" [taken from the name of Darger's 15,000 page "novel"] opened at the Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago, was moderated by Valerie Rousseau, a curator at the American Folk Art Museum. It included Elledge in from Atlanta; Brett, from London; the art historians Michael Bonesteel, a long time Dargerite, from the Art Institute of Chicago's school, and Jane Kallir, from Gallerie St. Etienne in New York who has published monographs on Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, and Grandma Moses.

All of the panelists tried to tackle the protean magnificence of Henry, who makes a very slippery subject. Darger can described as the "American Van Gogh," and yet Van Gogh lived in the world of art, went to art school classes and had famous artists as friends, while Darger had none of this. Darger lived at a subsistence level that made Van Gogh's life look luxurious. Both of them were highly evolved literary artists as well as visual ones. Michael Bonesteel argued that Darger's labyrinthine stream of consciousness novel is as much of an accomplishment as his pictures. Can they be compared to Van Gogh's letters? Van Gogh has captured the popular imagination because we see him as the tormented individual who releases us into a lushly colored imaginative world of our own freedom -- a romantic construction where only the insane tell the truth. Van Gogh has often been pictured as the "first modern man" because he saw the insanity within the regulated "normal" world and the truth within insanity.

But Darger's paintings, cinemagraphic within their hugeness, their use of shifting points of view, their contrasts of emotional darkness and light, bring us to a spiritual "tract," that place of profundity where consciousness declares itself. And we can all at some point remember that, or attach ourselves to it. As James Brett said: "We are responding to our own childhood being taken away from us by adults who don't give us a fair chance." Darger understood the heaven of being there unwounded before that happens, and the hell, the storms physical and emotional, afterwards. His Vivian girls are engaged in a battle to preserve their own goodness: the innocence of the inner boy, and of everyone.

So my first awakening at this year's Outside Art Fair was how deep Darger is. I can't leave him. He won't let me.

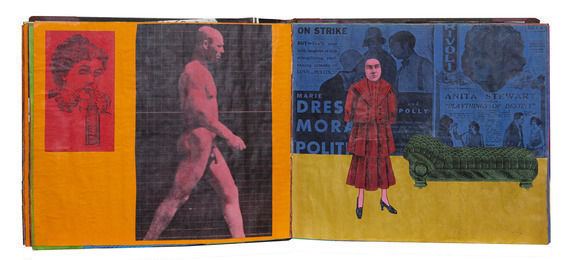

My second awakening was discovering an incredibly powerful new artist, Larry Lewis (1919-2004), who also sailed on this queer river of consciousness, though his story is a strange flip side of Darger. Lewis spent most of his life completely invisible in Norwalk, Connecticut, where he worked as a "male secretary" at United Oil Products, in an environment of Republican conformity. He married but had no children, studied art and tried to be a painter, with no success. He started making what could be called "collages," but were actually more like manipulated images using every kind of media combination, often put together into what can be called "scrapbooks," but which were more like the 20th century version of illuminated books, or handmade "unique books." He was obsessed with the movie stars from his youth -- Paula Negri, Theda Bar, Lillian Gish, Joan Crawford, but most especially Greta Garbo. Garbo was a queer icon pointing repeatedly to coded gender reversals. Lewis was also struck with the male nude image, which up to the 1970s existed mostly in either a clinicalized or classicized way.

That is, obviously, tactfully, removed from desire.

Any time the male image approached desire, especially within the pop, Hollywood culture that haunted Lewis, it became shamefully forbidden. You were quickly on scorched-earth, Sodom-and-Gomorrah ground. Lewis's meticulously done pieced images, using Edward Muybridge nude male imagery, bring this territory assertively closer to us. Like most outsider artists he asks the question: how do you say what needs to be said -- has to be said -- when most of us are too scared to ask the question?

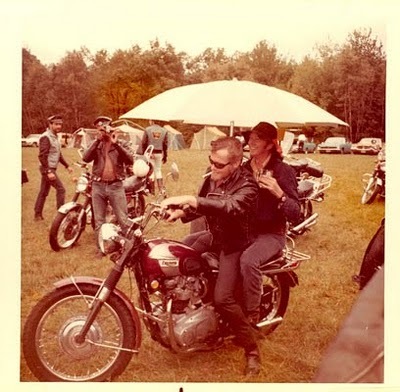

The third awakening came from discovering Scott Sieher's "Band of Bikers" series of found photographs from Zieher Smith Gallery. The phenomenon of the found work of art or photo is coming into prominence. Sieher's bikers were in a group of gay motorcycle clubs who produced "runs," that is social gatherings, that span pre-Stonewall to the present. "Band of Bikers" documents several runs from 1972. The photos were basically dumped "garbage" found in Scott's basement. His super alerted him to them, after a tenant had died leaving no real directive for dispersing his effects.

The photos are either posed, formal things, or very informal; mostly young or youngish men in biker leathers and jeans, or shorts out in a biker tent bivouac somewhere we don't know. The great awakening for me was that I knew some of the men in the pictures -- from my youngest years in NY -- I was 19, had just arrived in the city, and in the chummy queer fashion of the day met the president of the New York Motorcycle Club, an innocuous enough sounding organization, hiding a brotherhood of gay bikers. At that point, in the mid-1960s, queer bikerdom was an extremely outlaw situation, right out of Kenneth Anger midnight-show flicks.

Gays were supposed to wear cashmere, walk poodles, and drink brandy Alexanders. I quickly picked up with a group of leather guys who were the polar opposite of this, although by day some were bankers, doctors, or lawyers. Seeing these shots pushed me down the rabbit hole of time, to a place before dozens of my friends had died of AIDS, where being queer in New York was being part of a secret club whose signals and messages became a part of the culture of the city and that we are still deciphering, but it also underscored for me what Narrative is for art. It is the main thing that pulls us into it and keeps us there. Art does not tell a story; it is a story presented virtually whole. That is what drives us through Darger's battles between the Vivian girls and armies of the evil generals in academic robes, Larry Lewis's graphic books, and found photographs. That is what brings these outsiders directly into us, and keeps them there.

If you missed this year's New York Outsider Art Fair, there will be another rendition of it from October 23-26 in Paris. And who doesn't like a good excuse to go to Paris? For more information: info@outsiderartfair.

Perry Brass's latest book is Carnal Sacraments, A Historical Novel of the Future, Second Edition. He has published 17 books, including The Manly Art of Seduction, is a founding coordinator of the Rainbow Book Fair, the largest lgbt book event in the US, and can be reached through his website http://www.perrybrass.com.