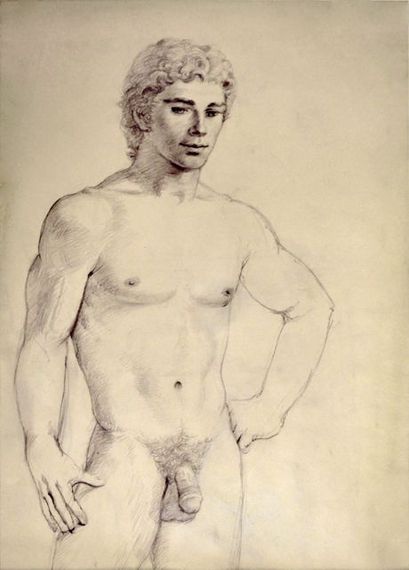

Paul Stone, Untitled, ca. 1960s, Pencil on brown paper, 12.25 x 9 in. Collection of Arthur Bennett Kouwenhoven.

Several ideas struck me while viewing the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art's current and very ambitious show "The Classical Nude" on display downtown in Soho until Jan. 4, 2015.

The first came from Jonathan David Katz's introduction to the show, displayed on the opening wall of the show: "For centuries queer people have looked at classical nudes for secret signs that speak to them . . . . Creating spaces where men could touch each other -- and women other women --the classical nude was . . . connected to the classical past that endorsed, even celebrated same-sex desire."

Jonathan David Katz also curated "Hide/Seek" at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington; the first queer-informed show that the Smithsonian had ever put together. In the "Hide/Seek" show Katz tried to pull together from sources covertly to blatantly queer an idea of what queer art is or can be. And in the Leslie-Lohman show we have another attempt to capture the unicorn of queer-informed art by bringing in all the coded sources. Strangely, dealing with the past in this category of art, this is exactly what you have to do.

My own definition of what is "gay art" (and here I'm using "gay" in a more 1950s or 1960s usage to mean everything pertaining to "gay people," the old term for today's lgbtq alphabet soup -- "lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered," and, lately, questioning or queer) is pretty simple: A piece of art that either openly celebrates same-sex desire or points to it; or reveals within its space some aspect of an outsider sexual experience that has been withheld.

In other words, it can be queer even if it has little if anything to do with "queerness," but it shows us a great deal that was not talked about back then, which might have included queerness.

A perfect example of this was Katz including an Albrecht Durer woodcut called "The Men's Bath," from 1498. In 2008, New York's Museum of Biblical Art near Lincoln Center put on a massive Durer show to highlight his biblical illustrations. They also included his "Men's Bath" series, about a dozen images. They were a knock-out; I kept wondering didn't anyone question the convergence of homoerotic imagery here--near-naked men eyeing one another, playing with one another seductively, smiling suggestively, and displaying themselves in unmistakable stages of "excitement" barely covered by linen g-strings?

A theme in the series was the comely naked youth surrounded by dumpy older men leering at him. I'd often wondered about Durer -- his breathtakingly, narcissistically handsome, page-boy coiffed self-portrait has caused many an art history student to blink -- but seeing this woodcut at Leslie-Lohman with the text under it openly pointing out its phallic and queer references (a waterspout posed like a penis, a suggestive flute player, a man holding a "pink," etc.) puts this work into a context for which it has long been waiting.

The same for bringing in Anne-Louis Girodet, a great, too long overlooked French painter (1767-1824) seen here with a small engraving but feted with a major show in 2006 at the Metropolitan Museum, lauding his rebelliousness, pyrotechnic painting skills, and surrealist, almost Wagnerian imagery -- often queer as the proverbial 3-dollar bill.

But the Met could never say that.

So the question is what is gay art -- something that points to queerness, something that queerness itself creates -- or both? In the second category, a small chalk study of the rear view of a falling nude male figure from 1540 by Michelangelo Buonarroti, borrowed from a private collector, is a star. It's this little piece of queer genius looking at you. It points directly to a small, Paul Cadmus male nude etching. Cadmus is definitely in the queer pantheon. In a large tempera on wood painting called "Bar Italia" done from 1953 to 1955 (tempera is a slow process)

Cadmus gives us both views of queer art: it points to itself, and is also made by a gay artist, so that it shows itself off in that light. This is one of Cadmus's famous "commentary" paintings, like "The Fleet's In," from 1934 that showed humpy sailors, feral prostitutes, and cruising queens, and that became a huge scandal for the U.S. Navy. In "Bar Italia" you have hustlers, cynical queens, paparazzi, tourists, kids--the whole schmere of a Roman street scene, all overseen by two classical marble nudes who seem to be blessing the transience of the scene by their own eternal presence.

So my second feeling seeing this show is that no matter where the queer eye lands -- whether it is on Andrea Mantegna's "Bacchanal with Silenus" (c. 1490), or Pontormo's red chalk drawing of a male back from 1528 (both artists in this show are text book Janson's History of Art History subjects), or goes to George Platt Lynes's really gorgeous photos or Nan Golden's work, or Duncan Grant's--it is always there. Sometimes it is only a matter of looking at what is obvious, as in the Platt Lynes, or Robert Mapplethorpe. But it is always a matter of how does the queer story come out, and why was it so hidden, so rejected, for so long?

Was it just sheer embarrassment and fear, or a taboo that only fed itself through its own repression, something at which the Catholic Church and Christian fundamentalism are expert? Or is it something deeper, that there is a constant spiritual crisis in humanity that queerness itself understands? That is, a longing to revert to a world of "classical" innocence, even under the bacchanalian excess?

The third idea was how many of the artists in the show I had actually had some contact with -- that is, in the small gay world before the Internet. I had known four: George Dureau, Robert Mapplethorpe, Paul Cadmus, and Paul Stone. The last was a real shocker to me, and I will explain that in a moment.

Dureau (1930-2014) I had known during my three-year residence in New Orleans in the early 1980s; I've just learned of his recent death. He was one of New Orleans's resident geniuses, a tourist attraction in himself--a total kook, eccentric, and, like many New Orleanians, flamboyantly hospitable. I came over to his studio to talk with him about using some of his photographs for a piece I was writing for a New York gay mag on working class gay men in New Orleans. He immediately sat me down to bourbon and lunch, and showed me half a lifetime's work. He talked a mean streak, never shut up, and was fabulous. At the end of two hours, I was punch drunk from listening. Later he called me at home to say he couldn't let me use a single shot because "it would go against the privacy of my models. They don't identity as 'gay,' like I do." We still became good friends, and had a lot of other times together. Dureau became famous for his photos of amputees, dwarfs, and a range of Crescent City characters. His models trusted him, and he wasn't going to shred that trust by putting them in a New York queer magazine.

Robert Mappelthorpe (1946-1989) was part of my young life in New York; I would see him at louche places like the baths and sex bars, and uptown at gallery openings or department store events that brought together downtown Warhol and uptown money. I especially liked meeting and talking with Sam Wagstaff, his handsome, socially-connected older partner. Sam was always more approachable and genial than Robert.

Paul Cadmus I'd met several times before his death at 95 in 1999. He was an incredibly attractive man who had been part of the great New York art world in the 1940s and 1950s, bringing together luminaries like the founder of the New York City Ballet, Lincoln Kirstein (Cadmus's one-time lover, then brother-in-law), George Balanchine, Platt Lynes and the writer Glenway Wescott, Charles Henri Ford and Pavel Tchelitchew. What I realized was that Cadmus was part of a small coterie of queer artists, including George Tooker, who revived the Renaissance use of egg tempera, one of the most exacting and painstaking of media.

This brought me to the last of this group, and quite a shocker for me: the artist Paul Stone (1928-1976). Stone lived most of his life in Savannah, Georgia, where I was born and grew up. In 1964, at the age of 16 I decided to become an artist and go to art school. I'd heard about Stone, he was then the most famous artist living in Savannah: I called and asked if I could show him my work. He graciously invited me to his home, in a townhouse near the local YMCA, on one of Savannah's beautiful squares; it was no secret that he had married a wealthy younger Savannah woman who was drawn to Stone's talent. He was a trim, good-looking man a couple of years younger than my mother. He spoke in a cultivated Tidewater accent, looked at my student portfolio, and said to his wife, who appeared for a moment, "Mr. Brass is a follower of the German Expressionists."

I had no idea if this were true, but it made me feel good. He showed me some of his things, including a beautiful drawing of a young man in a bathing suit lying prone next to a swimming pool. He told me that he had found the model at the Y, and pointed out the softly-shaded planes of his shoulder and pectoral muscles. "I think this is very beautiful," he said, "if you like those things." I blushed.

He showed me some of his tempera work, including a large painting of a young carnival worker bursting out of his T-shirt. Stone had taken up tempera from his infatuation with Andrew Wyeth--he often went to visit Wyeth in Chadd's Ford, Pennsylvania. Later, in subsequent conversations, he spoke of these visits as "pilgrimages." I was young, and not crazy about Wyeth, and I already realized that Paul Stone was concealing way too much. After I left Savannah a year later, I hardly thought about him, until I saw a beautiful male nude of Stone's in this show. Then I learned the rest of his terrible story.

In 1976, he'd fallen in love with a younger man who rejected him. He walked out into one of the side streets of Savannah, poured gasoline on himself, and lit a match -- immolating himself like a Buddhist monk. I can still hear his voice talking about the drawing of the young man lying by the Y pool. "These things are beautiful for those who like it."

We are slowly, finally, coming to understand the amazing narratives of gay art--this show is either a beautiful beginning, or simply another link in that understanding. It's also a milestone for the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art : 85% of the show is borrowed from other museums and international collections. This means that the world's only museum of gay and lesbian art is growing up and becoming recognized.

The Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art is at 26 Wooster Street in the Soho area of Manhattan. It is free to visitors. For more information: www.LeslieLohman.org.

Perry Brass has published 18 books, and is the author of the bestseller The Manly Art of Seduction, How to Meet, Talk to, and Become Intimate with Anyone, and King of Angels, a gay, Southern, Jewish coming of age novel set in Savannah, GA. His next book will be The Manly Pursuit of Desire and Love, How Connecting with Your Own Deeper Self Can Bring You Happiness, Sexual Satisfaction, and Save Your Life in a Difficult World.