I don't know if Howard Zinn was a baseball fan, but I'm sure that the author of A People's History of the United States would have loved the documentary film Not Exactly Cooperstown. Just as Zinn told the story of America from the perspective of its rebels and outcasts, Not Exactly Cooperstown looks at baseball from a bottom-up point-of-view. It profiles the Baseball Reliquary, which former Yankee pitcher Jim Bouton called a "People's Hall of Fame," one that allows fans to vote and, as a result, enshrines the sport's dissenters, free spirits and tradition-busters who challenged the baseball establishment.

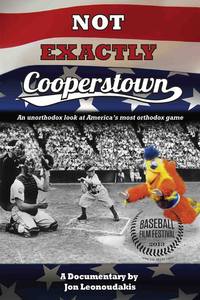

The documentary shares many of the Reliquary's characteristics. It is irreverent, quirky and -- for filmmaker Jon Leonoudakis as for Reliquary founder and director Terry Cannon -- a labor of love. Both are baseball fanatics -- the origin of the word "fan" -- who embrace the sport by celebrating its offbeat side.

The film includes interviews with artists, writers, fans, former major leaguers like Bouton and Bill "Spaceman" Lee, well-known sportswriters like Arnold Hano and former minor league infielder Ron Shelton, who went on to direct films like Bull Durham and Cobb.

Released in 2012, the colorful documentary has developed a cult following among baseball aficionados. It will be shown this Saturday (February 15) at 12:30 p.m at the Laemmle Playhouse 7 in Pasadena, as part of the inaugural Pasadena International Film Festival. Leonoudakis will be on hand to answer questions after the screening.

Based in Pasadena -- known for the annual Rose Bowl football game but also the hometown of baseball legend Jackie Robinson -- the Baseball Reliquary includes a research archive, a traveling museum, and the Shrine of the Eternals, the organization's alternative to baseball's official Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, a small town in upstate New York that was chosen to promote the myth that Abner Doubleday invented the sport there.

In contrast, the Reliquary bursts baseball's official myths by giving voice to the players, fans, owners, umpires, sportswriters and others who love the game, rather than the business, of baseball. So, not surprisingly, its Shrine of the Eternals includes many individuals who aren't likely to have their plaque hanging on a wall in Cooperstown.

Each year since 1999, it has inducted three individuals -- players, executives, fans, umpires, writers and others -- into its Shrine at a raucous ceremony in July at the Pasadena Central Library. A handful of the Eternals -- Roberto Clemente, Jackie Robinson, Yogi Berra, Casey Stengel, Bill Veeck, and Negro League stars Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson -- have dual citizenship in the Cooperstown Hall of Fame, but most of them gained entry to the Shrine because of their unorthodox contributions to the national pastime.

Not surprisingly, Curt Flood was one of the first three people inducted into the Shrine. The All-Star and Gold Glove Cardinals outfielder in the 50s and 60s risked his career by suing Major League Baseball to overturn the sport's indentured servitude system called the reserve clause. His courageous action eventually led to the free agency that players enjoy today. Not Exactly Cooperstown includes a poignant clip of Flood's wife accepting his induction into the Shrine of the Eternals.

The film also highlights another Shrine immortal, Lester Rodney, the sports editor of the Daily Worker, the Communist Party newspaper, who played a key role in exposing baseball's racial hypocrisy and pushing for integration as early as the 1930s.

Marvin Miller, the first executive director of the Baseball Players Association, has been nominated to the Cooperstown Hall several times, but each time the anti-union business-dominated selection committee found an excuse to keep him out.

Miller, who traveled from New York City to Pasadena in 2003 to accept his Shrine induction plaque, received a standing ovation as he came to the stage at the library auditorium, where the ceremonies are held each year. Miller, then 86 years old, reminded the crowd about baseball's working conditions in the mid-1960s, when players first began talking about forming a union and asked Miller, an official with the steelworkers union, to join their movement.

Said Miller:

In other industries, the employees were not owned by their employers; they were not property, and they could not be traded or sold for cash. The employees could not be victimized, blacklisted or denied employment. But in baseball, all these conditions existed for about 100 years.

Pam Postema, who was voted into the Shrine in 2000, began her umpiring career in the rookie-level Gulf Coast League and steadily progressed through the ranks, eventually reaching the Triple-A Pacific Coast League in 1983. But after six years of stellar service, she was denied an opportunity to umpire in the majors. She filed a sexual discrimination lawsuit against Major League Baseball in federal court, which was later settled. In 1992, while working as a truck driver for Federal Express in California, she published her no-holds-barred autobiography, You've Got to Have Balls to Make It in This League.

In 2010, the Reliquary sponsored a day-long celebration of the 40th anniversary of Bouton's groundbreaking expose of baseball's locker room culture, Ball Four. The iconoclastic Bouton spoke and participated in a panel discussion about the book's cultural significance, and opened the Reliquary's exhibit, "Ball Four Turns Forty." Bouton was an All-Star pitcher for the Yankees who won 41 games in 1963 and 1964, including two World Series victories over the St. Louis Cardinals. As a player, he triggered controversy for his strong pro-union views and his opposition to the Vietnam war. But his greatest impact on the game came after he retired -- following an unsuccessful comeback effort as a knuckleball pitcher -- when he wrote the best-selling Ball Four, which forever changed baseball sports writing as well as the public's perception of its baseball heroes.

Other personalities inducted into the Shrine include:

• Shoeless Joe Jackson, who was unfairly banned from professional baseball after the Black Sox scandal of 1919.

• Dr. Frank Jobe, who invented the operation typically called "Tommy John surgery," which has resurrected the careers of numerous pitchers.

• Jim Abbott, the left-handed pitcher who was born without a right hand but had a stellar MLB career, and Pete Gray, the one-armed outfielder whose one-year sojourn in the majors was made possible due to the player shortage during World War 2.

• Bill "Spaceman" Lee, the quirky Red Sox pitcher who reflected the counter-cultural values of the 1960s and 70s, and Mark Fidrych, the equally eccentric fastballer for the Detroit Tigers, who thrilled fans with both their mound antics and occasionally brilliant hurling.

• Ila Borders, a left-handed pitcher, who played on her college men's baseball team and is still the only woman so far to play in the men's professional minor leagues (1997-1999). She took time off from her firefighter training program to accept her induction into the Shrine in 2003.

• Jimmy Piersall, the one-time Red Sox star outfielder whose battle with mental illness was portrayed in the 1957 film Fear Strikes Out (based on Piersall's autobiography) starring an incredibly miscast Anthony Perkins, who clearly lacked any athletic skill.

• Minnie Minoso, an underappreciated All-Star, base stealer and Gold Glove outfielder, born in Cuba, who battled racism in the United States, entered the majors in 1949 and played in every decade through 1980, when he played in two games for the White Sox at age 54. The indefatigable Minoso made a brief appearance with the independent St. Paul Saints in 1993 (at age 67) and returned to the Saints in 2003, drawing a walk in his only at bat, thus becoming the only player to play professional baseball in seven different decades.

• Bill Buckner, who played for the Cubs, Red Sox and Dodgers over a 22-year major league career, won the 1980 National League batting championship with a .324 average, twice led the league in doubles, and drove in more than 100 runs three times, but is unfairly best remembered for allowing Met Mookie Wilson's ground ball go through his legs in the 1986 World Series, turning a Red Sox victory into a defeat, and making Buckner a forever fall guy.

• Japanese-American baseball pioneer Kenichi Zenimura, a player and manager, who during the 1920s and 1930s led barnstorming tours of professional American players (including Negro League players) to Japan, and during World War 2 organized baseball leagues in America's internment camps.

• Emmett Ashford, who spent nearly 20 years as a minor league umpire before becoming the first African-American umpire in Major League Baseball, from 1966 to 1970.

Another Shrine inductee is Bill Veeck, whom Cannon calls the Reliquary's "spiritual guru." In his 50-year career as a major league team owner and executive, Veeck was the greatest public relations man and promotional genius in the sport's history. As owner of the St. Louis Browns, Cleveland Indians and Chicago White Sox, Veeck introduced the "exploding scoreboard" and fireworks whenever a home team player hit a home run. This kept fans entertained, which was particularly important for Veeck, whose teams were often at the bottom of league standings.

It was Veeck's idea to add players' surnames on the back of their uniforms, and to bring 3'7" little person Eddie Gaedel to the plate in 1951 in one of the most daring promotional stunts ever. Veeck also persuaded a reluctant Harry Caray, the White Sox announcer, to sing "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" during the seventh inning stretch -- a ritual that soon became a beloved tradition.

Veeck infuriated his fellow owners with his antics and his progressive politics. He had wanted to bring blacks into the majors for years but was blocked by fellow owners, and he gets too little credit for signing Larry Doby, the first African-American player in the American League, a few months after the Dodgers hired Jackie Robinson. In 1970 he even testified on behalf of Flood's effort to overturn the reserve clause.

One of the most moving moments in Not Exactly Cooperstown is Dock Ellis' acceptance speech at the Reliquary's first induction ceremony in 1999. A first-rate hurler for the Pittsburgh Pirates in the late 1960s and early 1970s who helped his team get to the World Series and once pitched a no-hitter while high on LSD, Ellis never received the accolades he deserved in part because he was outspoken about racism both within baseball and within society. With his son and mother in the Reliquary audience, Ellis was introduced by a letter Jackie Robinson wrote to him, admiring his courage and reminding him that people who challenge the establishment are often vilified. Ellis delivered a talk that had the Reliquary crowd in tears.

Not Exactly Cooperstown also captures the tragic but also redemptive story of Steve Dalkowski, often considered the fastest pitcher in the history of baseball, who was inducted into the Shrine in 2009. Few baseball fans know that one of the characters in Bull Durham -- hard-throwing pitcher "Nuke" LaLoosh, played by Tim Robbins -- is based on Dalkowski, who pitched in the Orioles' farm system for nine erratic seasons (1957-1965), typically leading the league in both strikeouts and walks. He played before the invention of the radar gun, but witnesses claim that his fastball reached 110 or even 120 miles per hour.

Wildness -- of his fastball and his hard-drinking lifestyle -- kept him out of the majors. After leaving baseball, Dalkowski lost control of his life, scraped by as a migrant farmworker, was often homeless, and lost touch with his family. The film describes his sister's determination to find him and help him get sober. She accompanied him to the Reliquary's induction ceremony where, despite suffering from alcoholic dementia, the 70-year-old Dalkowski signed autographs for the adoring audience of baseball junkies who knew all about the left-handed legend.

The Reliquary's 200 voting members (anyone can join for $25 a year) know their baseball and can compare statistics and rank the "best" players in the game's history, but, according to Cannon, they select people for the Shrine of the Eternals based on other criteria.

We prefer people who are opinionated, outspoken, not satisfied with the status quo, ready and willing to place principle over profit, and willing to overcome personal demons and social obstacles.

Like many other baseball events, the Reliquary begins its annual event each July with the National Anthem, but true to its free spirit the song has been played on a harp, violin, ukulele, Erhu (a Chinese violin), a trombone ensemble, a pedal steel guitar, a flute, musical glasses and musical saw.

Each year the Reliquary gives the Hilda Chester award (named for a large-lunged Brooklyn Dodgers fan in the 1940s and 50s) to an individual who has taken baseball fandom to unusual lengths. The 2002 winner, for example, was Dr. Seth Hawkins, a retired professor of speech and communications at Southern Connecticut University, who had attended at least one regular-season game in all 66 stadiums used for major league play since 1950 and had been present for every 3000th hit recorded in the major leagues since 1959 -- 17 in all -- as well as Hank Aaron's record-breaking 715th home run and Pete Rose's 4000th career hit.

Another award, in memory of historian Tony Salin, goes to a person who has expanded our knowledge, understanding and/or appreciation of baseball in unusual ways. Last year's recipient, Steve Bandura, runs a youth program in Philadelphia and coaches the Anderson Monarchs little league team. In 2012, in honor of the 65th anniversary of Jackie Robinson's breaking of the color line, Bandura rented a 1947 non-air conditioned, bathroom-less tour bus, and took the team -- fifteen 10- and 11-year-olds -- on a 22-day, 4,000-mile barnstorming tour in the tradition of the old Negro League teams. It included a visit to Robinson's gravesite in Brooklyn and stops in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Kansas City and other cities.

Along the way, the Monarchs played 17 games against local little league teams, and the young athletes got to visit historic baseball sites, meet surviving players from the Negro Leagues, and learn much about the legacy of African-American baseball in the years before the game's integration.

Cannon, a library assistant at the Allendale Branch in Pasadena, started the Reliquary in 1996 not only to celebrate athletes but also to collect odd baseball artifacts. Its quirky assortment of baseball memorabilia includes Dock Ellis' hair curlers, a jockstrap worn by Eddie Gaedel (the aforementioned little person who had one at bat for the lowly 1951 St. Louis Browns owned by Veeck), several baseballs signed by Mother Teresa, and, as the New York Times described it, Babe Ruth's "half-smoked cigar purportedly rescued from a Philadelphia brothel in 1924." The Reliquary collection also boasts a mid-19th century soil sample from Elysian Fields in Hoboken, N.J., where the first baseball game ever played between two organized teams took place in 1846.

The Reliquary's artifacts and collections are currently housed in Cannon's home and in a rented storage unit, but he is currently negotiating with a Los Angeles area college to serve as the repository for its research materials, which would be made accessible to students, scholars and the interested public.

Under Cannon's careful but unpaid guidance -- and a bare-bones $5,000-a-year budget -- the Reliquary has also worked with academic and amateur historians to retrieve and reveal little-known aspects of baseball's past.

Not Exactly Cooperstown highlights the group's Latino Baseball History Project, a collaboration with California State University, San Bernardino, that has uncovered the story of amateur and semi-professional leagues within Southern California's Mexican American communities that was once a significant source of ethnic identity and pride. The project includes oral histories of now-aging players, a permanent archive, traveling exhibitions, public talks by scholars and enthusiasts, and a Web site.

The film captures the fun, excitement, seriousness and wackiness of the Reliquary's devoted members, who come from around the country and all walks of life, and who no doubt disagree about politics and morality, but share a common obsession with baseball.

Leonoudakis, an accomplished filmmaker and producer, says that he had lost his enthusiasm for baseball after the 1994 strike and cancellation of the World Series, the steroids scandal and the game's increasing domination by corporate titans and greedy players.

"The game I grew up loving had turned into a distorted, hideous creature unworthy of my time and money," he recalled. "It was like getting divorced after 44 years of bliss. I was crushed."

Then, in 2002, Leonoudakis discovered the Reliquary and attended its annual induction ceremony.

It was a transformational experience. Fans and historians were honored. Keynote speaker [sportswriter] Peter Golenbock launched into a scorching condemnation of George Steinbrenner. They were inducting Minnie Minoso in their hall, and the Cuban Comet was there in person, happily spending time with attendees. I came out of there back in the fold, feeling like I'd just been to a super-charged revival meeting.

Peter Dreier teaches Politics and chairs the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His most recent book is The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame (Nation Books, 2012).