"What are masterpieces?" asked Gertrude Stein in the very title of one of her best known books. "What is mastery?" she could have been asking. Can one separate the art from its maker, the dancer (as Yeats asked in turn) from the dance? A masterpiece can only be made, logically, by someone capable of mastery. Is that artist then a master? Or to be a master must that artist demonstrate, time and again, her ability to achieve mastery?

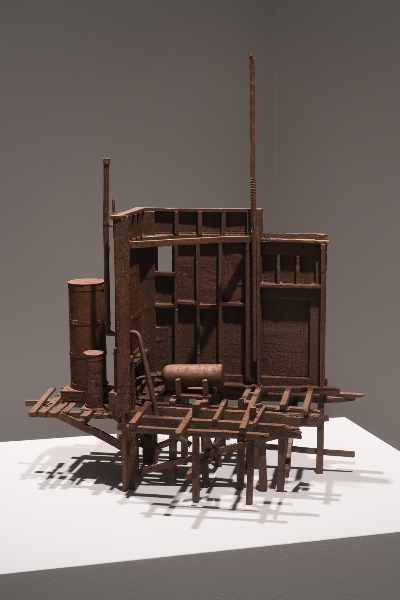

MICHAEL McMILLEN, Anxious Bay, 2010, Bronze, 16 1/2 x 16 x 7 1/2 inches, Courtesy LA Louver, Venice CA

Should I even be asking these questions? Isn't the whole issue of "mastery" and production of "masterpieces" suspect, a means of maintaining cultural hegemony - by whomever over whomever else - via a "master narrative"? I keep thinking so, then keep encountering mastery, moments of quintessence and transcendence focused into individual artworks, as often as not realized by people who have realized such moments before - indeed, people upon whom we have come to depend for such moments. Finally, as long as I trust myself not to regard other artists and works of merit as diminished by the presence of masterpieces and the existence of masters, I can accept that masters and masterpieces do exist. Art itself does not exist ideally to bring forth masterpieces; the discourse of art is far larger than even its best moments, and it is possible to learn more, much more, from failure or adequacy than from (near-)perfection. Mastery is a condition, like any other. And unlike any other.

LAURIE ANDERSON

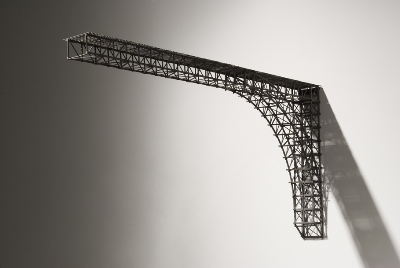

MICHAEL McMILLEN, Bendigo, 2009, Birch and maple, 28 x 57 x 5 inches, Courtesy LA Louver, Venice CA

Two recent displays in Los Angeles set me on this perilous rumination, displays of mastery from artists who have long moved me with the twinned ineffability and logic - the simultaneous need to exist and existential improbability - of their work. If Laurie Anderson didn't do what she did, and if Michael McMillen didn't do what he did, someone would have to, but I'm not sure anyone else could, at least quite as they do it. Their aesthetics are rich and deep and resonant, they realize their distinctive visions with exacting technical care and a steady yet expansive, self-conscious yet free-flowing poetics. Their genius is felt not in the ready, perhaps instant, recognizability of their work - although their art requires such distinctiveness to maintain its persuasion - but in its abiding ability to transport its beholders by oscillating between fantasy and reality, banality and magic, intimacy and universality, the dreamt and the dumb. In this regard I'm tempted to compare them, at least at their best, to Shakespeare or Beethoven or Velazquez (to draw just from the White Guy panoply), but these two masters aren't Old - well, they're both over 60, but you know what I mean. In their latter-day vitality, Anderson and McMillen hit it in a way that, for all their latter-day references - and vagaries of media (especially, but not solely, in Anderson's case) - you know, you just know, are going to ring true long after they and we are gone.

MICHAEL McMILLEN, Witch of Draconis, 1983, Wood and metal, 72 x 24 x 36 inches, Courtesy of LA Louver, Venice CA

Anderson and McMillen are American masters, dreaming American dreams (many, but not all, nightmares). They are also Boomer-generation masters, but only Anderson's anxiousness and (growing) poignancy speak to the aging mass of duck-and-cover kids. The landscape McMillen describes is more classically, generically American, its tropes and markers as redolent of WPA photography and film noir as of TV ads and rock-and-roll. McMillen's objects and installations capture the lonely back side of the American century - suggesting that it might all have been a Potemkin village, a vast machine of illusion whirring away behind a wizard's screen. Anderson's digitally driven performances capitalize on that very screen, alluring us with the sparkle of an old-fashioned [sic!] light show and the techno-gloss of seamless sound and image segues. She doesn't try to suspend our disbelief; seduction is best done with a wink, not a lie, and Anderson deliberately scales her projections and even her vocal distortions absurdly, dwarfing herself with the very amplification of her sounds and her vision. McMillen, by contrast, shrinks his subjects, usually down to toys, but sometimes to 2/3 size, tempting us with tactility and apparently easy heft just as Anderson tempts us with ephemerality and gigantism.

LAURIE ANDERSON in performance

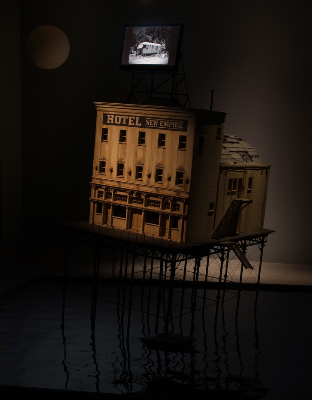

MICHAEL McMILLEN, Lighthouse (Hotel New Empire), 2010, Mixed media (with digital motion picture projection), 97 x 132 x 144 inches, Courtesy LA Louver, Venice CA

Anderson's latest live solo performance, Delusion, played one night as part of the UCLAlive! Series. (Originally produced this past winter for the Vancouver Olympics, Delusion was also presented in Santa Barbara and San Francisco, and Anderson takes it next to Italy.) McMillen's latest exhibition, "Lighthouse," is on view at LA Louver in Venice (45 N. Venice Blvd., until Nov. 6). Neither artist has introduced much new into their form or their content; even Anderson's seemingly new-found "personal voice," manifested in her meditation on her mother's passing, returns her to the first-person narrative of her early performance works, while McMillen's montage-film, projected onto the billboard sitting atop his creaky, tilted lighthouse-hotel, is the latest in a string of such flicks, collaged out of newsreels, war-era advertisements, instructional reels, and the like, that he's been insinuating into his installations for the past several years. But damn if they both haven't woven their auras around our consciousnesses just as thickly and tightly as ever. It's not like the Rolling Stones playing their oldies or the New York City Ballet staging Balanchine classics or like that; we don't go to Anderson simply hunkering for more weirdly amplified violin or McMillen for more miniature tenements, and if that were all we got, we'd knock them for churning out mere souvenirs of their mastery. Wedded as they may be to their respective image banks, Anderson and McMillen want to find new things to talk about, new sensations to provide, even as they re-explore their habitual themes. Maybe that's what makes them masters: they can do the same ol' same ol' and yet be letting us in on whole new revelations - in among the same ol' revelations.

MICHAEL McMILLEN, Furnace Cove, 2010, Bronze, 24 1/2 x 21 x 15 inches, Courtesy LA Louver, Venice CA

I realize I've described little of what either Anderson or McMillen has set before us in these latest presentations. It's not that description beggars the issue, or even that what they do is hard to describe. It's more that the little I have described must suffice here for the larger argument, an argument that can only be driven home by your witness, not mine. Both Delusion and "Lighthouse" take place in the dark - a factor in their process of enchantment as obvious as it is necessary, but indicative of the palpability and immediacy involved in the experience(s) they convey. These shows do not happen behind a computer screen; they happen in real time and space - and then again inside your mind. They are irreducible in their charming fantasy and fantastic charm. Are they masterpieces? You judge if you can. Are they masterful? Take it from me...

MICHAEL McMILLEN, Chamber of Revelation, 2003, Sign painters enamel on window, 28 1/2 x 24 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches, Courtesy LA Louver, Venice CA