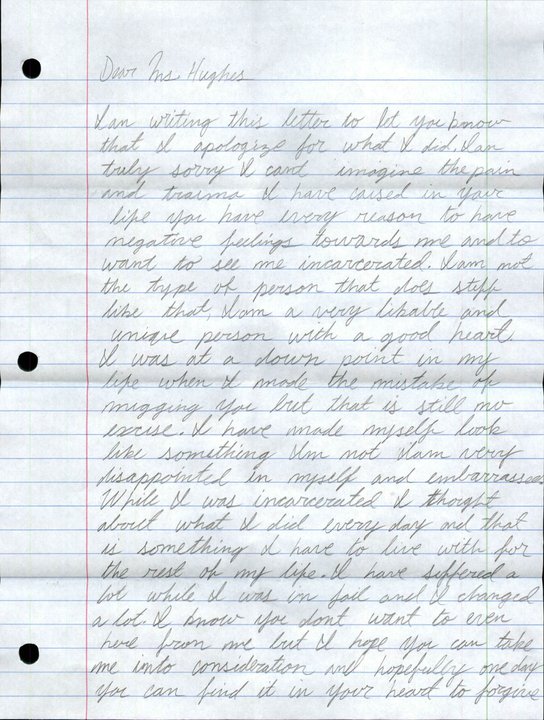

Last January, the most incredible thing happened: I received an apology letter from a guy who tried to mug me the previous fall. He wrote the letter on lined notebook paper with a pencil in beautiful script, the kind of script your grandparents were taught in grammar school. Delivered to me via the District attorney's office, the stunning letter expressed remorse and asked for forgiveness that the mugger didn't expect to receive. The apology didn't dismiss the crime. The mug had served jail time and I was glad for that. It didn't matter that a judge may have ordered him to write the letter or that he may have written it to get parole a little sooner.

This apology closed the loop on the crime and put a nail in the coffin of 2010, a year that had been far from stellar. More importantly, as I look back at the past year since receiving the letter, I realize that it played an even more significant role: it reminded me that everything was still possible in the world. It kicked off a year filled with inspiration, imagination, adventures, ingenuity, and enthusiasm found in amazing people and in experiences that were often rooted in the arts, but often sprung from a simple curiosity about the world and from a desire to live a life defined by one simple, overarching principle: to suck the marrow out of life every single day and be very grateful for the extraordinary people in my life and the remarkable experiences that I was (and still am) lucky enough to enjoy.

In May, an artist named Agnes Bolt lived inside a large, clear plastic structure (a.k.a. the "bubble") inside my condo for one week. During this time, we were to live by a set of rules that Agnes conceived and I quickly broke. A few of my infractions: not preparing two nourishing meals daily (I often ordered take-out and had cooked a lasagna that we ate for at least three days), and not using the specially devised communication tube to speak with her about non-art subjects (about art we were allowed to speak freely but I decided that because this whole experience was an art project, anything we talked about could be considered art and therefore free from the confines of this rule).

From the moment she arrived at my door ready to assemble the bubble, the air was filled with tension, which rose quickly over the next few days until a plot thickening clash occurred: the Humane Society showed up at my door to investigate the reported abuse of a large animal that someone had allegedly heard howling in pain inside my apartment. Turned out to be one of her "whimsical" pranks. I nearly threw her out. But we persevered and we found a way to connect with each other by the end the week. My eyes misted over when we parted and what felt like the worst experience of my life turned out to be one of the best. I'd learned a massive amount about life, art, and myself from this art project and that's what great art ought to do.

For my birthday in October, I experienced an amazing land art installation: Walter deMaria's "The Lightning Field," which was comprised of four hundred thin lightning rods (2" diameter) spaced evenly apart on a scrubby field measuring one kilometer by one mile, located near Quemado, New Mexico, about three hours drive from Santa Fe in the middle of nowhere. A ping pong-playing cowboy named Robert Weathers drove us another 45 minutes from Quemado to a spare yet perfectly outfitted cabin that sat just in front of the lightning rods and he left us there over night with a Southwestern-style casserole, eggs and bacon, and some granola mix. Cellphones didn't work, there was no tv or radio, no books, not even pictures to decorate the walls. Just you, five other people, and a bunch of lightning rods.

No lightning hit while we were there. In fact the weather could not have been more perfect -- 75 degrees, and a sunny, cloudless sky. And yet it was absolutely thrilling and amazing to watch the light work its way over the rods and back again in the morning. That night, the weight of the stars in a sky unpolluted by man felt heavy, like the constellations were pushing down hard on us. It was a moment in which I briefly understood absolute beauty. In the morning, we woke up before dawn and each went into the field of rods in different directions, slowly picking our way through the brush in darkness. I found a clear spot to sit and watched the sun rise. Just as the ball of fire peaked over the horizon, a large crow flew directly over my head and I could hear the sound of wind in its wings. Whoa. I'd never heard this sound before and its simple splendor startled me. Another moment of absolute beauty.

Also in October, I visited Haiti to participate in the transCulturel Forum, which brought artists from many French-speaking countries to Haiti to make art with Haitian artists and art students. The week culminated with an exhibit at the École national des arts. I also visited artist studios and an entire village devoted to metal work. Despite the devastation and struggles that afflict Haiti, the artists I met affirmed my belief in the basic human instinct to make art, to make beautiful things, and to express their humanity through art.

The year ended with artist/activist Adrian Parsons embarking on a hunger strike to win us D.C. residents the inalienable right to be represented by our lawmakers. Until he began this hunger strike, I'd forgotten that I live in a place that taxes me without proper representation in Congress. And that's exactly the problem. I'd forgotten about a basic freedom that 308,000,000 other American citizens enjoy. If I'm not going to remember, then why should the rest of the country care and make any effort to right this wrong? Moreover, D.C. is filled with an abundance of creative richness and intellectual awesomeness. This civil rights snub is not merely an injustice but an insult to those who call DC home.

I admire Adrian for this act, for taking action rather than sitting back and complaining about it. I am not so sure that starving himself for 25 days to the brink of death did much to achieve voting rights for D.C. I am not so sure that Adrian isn't possibly crazy. But I am sure that it takes one man's extreme action to catalyze and mobilize change. And that is what I believe great art does. This isn't really about Adrian, though. It's about everyone who has ever taken a stand for what they believe and who has tried to live a life worth examining. These people remind me that everything is still possible in the world.