Written by Keryn Breiterman-Loader

During my first quarter at Stanford, I got sick a lot. This was very unusual for me and was a little mysterious, since I was practicing all my healthy behaviors -- eating well, sleeping well, and exercising daily. I blamed my frequent illness on living with so many people in a dorm (I figured there were more germs when you're sharing a bathroom with 20 and a dining hall with 700). I even blamed the "West Coast Germs," which certainly my body needed to adjust to after having lived in Miami almost my entire life.

In order to protect myself, I became germaphobic -- always using a napkin to hold the salt and peppershakers and serving utensils in the dining hall. Whenever anyone in my dorm got sick, I went to great lengths to spend as little time in the dorm as possible. As soon as I felt tired, I would head straight to bed. I washed my hands so often, and used so much hand sanitizer that the skin on my hands dried out, and began to crack and even bleed a little. Though I was making friends, these people that I had only known for a couple months didn't compare to my family and the tight-knit group of friends I had back at home, and my further self-isolation from being sick and my fear of sickness didn't help. By the end of my first quarter, I felt lonely and anxious.

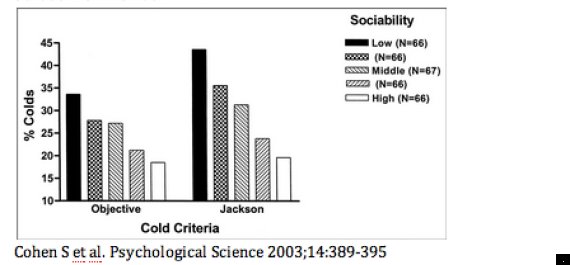

About a year and a half later I was sitting in a psychology class when it all came together -- I learned about the incredible influence of anxiety and stress on the immune system. In fact, I feel relatively confident that the loneliness and anxiety I experienced from my germaphobia contributed more to my sickness than the actual germs I was afraid of. In class I learned that the more social ties a person has, the less likely they are to get a cold, and when sick they experience less severe symptoms. [1] Additionally, the greater a person's sociability, the less likely they are to get a cold, independent of baseline immunity, health behaviors, demographics, and stress hormones.

This made sense in terms of explaining why I got sick so much -- as a relatively shy person, the fact that I didn't yet have close friends or strong integration into a community trumped all my other healthy behaviors, and even the initial strength of my immune system. In many other ways, however, it didn't make sense. Wouldn't spending more time around people make us more likely to get sick? How is it possible that socializing protects us from getting a cold?

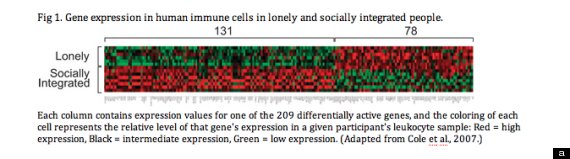

Now this is where the lecture really got interesting. The guest lecturer on that day, Steven Cole from UCLA, explained to us the research he had been doing on the molecular pathway of this social regulation of our gene expression. He looked at what genes were being expressed in lonely people and socially-integrated people and then compared to see if there was a difference. He did find a difference, and interestingly, the majority of genes influenced by our social connections are genes coding for immune response. People who feel socially isolated or detached, or experience a chronic threat of social losses, experience an upregulation in inflammatory genes and a downregulation in immune response genes.

Whoa, I never knew that spending time with friends could physically change the strength of my immune system on a genetic level. Dr. Cole went on to explain that this response developed because it was evolutionarily beneficial. As we evolved on the savannah, threat from bacteria and viruses was heightened when we were around people, and so our bodies learned to send immune reinforcements when we spent time around other humans. Further, we were most vulnerable to threat from wild beasts when we were alone, and so in this circumstance our bodies learned to divert precious resources away from long-term repair and immune strength and toward more urgent matters of increasing our vigilance, heart rate, and blood flow to extremities in order to prepare us for fight or flight should we be attacked.

Interestingly, in this study people's subjective perception of their social connection was more predictive of their gene expression than the objective measures of social connection. This suggests that the quality of our relationships may be more important than quantity. When I first moved to college, I was surrounded by more people than ever in my life, yet I felt much more socially isolated in this new place where I knew no one.

Before coming to college, I generally viewed spending time with friends as a luxury, a treat, something I deserved only after I had dealt with my work and responsibilities. I started off college with the same strategy but soon found that it was non-functional. I couldn't fall back on the strong social ties, support, and integration that had been built around me my entire life. If I wanted social support or closeness, I had to actively seek it out. Further, my work and responsibility load became never-ending, such that if I needed to be done before spending time with others, then I would always remain alone.

I remember one night, lying in bed alone in my room because I felt like I was getting sick again. I called my parents and cried to them in the dim light of my dorm room that no one really noticed when I retreated for a couple days to my bed, that no one but myself was there to take care of me when I was sick, and that I still had so much work that I needed to complete. I remember that night my parents encouraged me to go out and spend more time making friends. They told me not to worry about putting off some work to go out and cultivate relationships with people. From that day on, my priorities shifted a little, and I gave myself permission to recognize that my social needs were important and valuable. As I spent more time with others, my relationships strengthened, until I again formed a core group of friends and people I felt close to. Over time I became less lonely, I felt safer, happier, and by the middle of my freshman year I was back to my healthy self. I learned about the inherent value of strong relationships, and so maintaining them became a top priority.

Though by the end of freshman year I had a number of close friends and a great community, it has still been a struggle to find the right balance of the time and energy that I spend on maintaining and deepening my social connections. Stanford is an amazing place with endless opportunities, but because Stanford students tend to want to be a part of, and excel at everything, it can become very overwhelming very quickly. Being a student at Stanford is like trying to take a sip of water from a fire hose. Though Stanford students may have an aura of calm and California chillness, this only plays into the "duck syndrome" that exists on campus, where everyone seems calm and collected and but is paddling frantically just beneath the surface. This makes it a challenge to prioritize relaxing with friends but also makes it that much more important.

I know Stanford students aren't the only ones that often feel overwhelmed, and many of us in modern society have a similar experience of chronic stress in trying to balance our responsibilities at work and at home. Because stress is linked to a wide variety of negative health outcomes, social connection also contributes to health through its buffering effects against stress. [2] Perhaps stemming from the evolutionary fact that we could better fight off beasts, acquire food, and build shelter with others, or perhaps from the simple fact that support from others helps us deal with challenges, social support can greatly contribute to stress reduction. Consequently, social support is associated with less cardiovascular reactivity to stress (such as heart rate and blood pressure), lower resting blood pressure and cortisol (a stress hormone that impairs immune function among other things) levels, and greater immune response. [3] Further, social support is a healthy way of dealing with stress, which helps buffer us against engaging in other, less-healthy strategies, such as overeating, smoking, or alcohol and substance abuse. [4]

I recognize that once I graduate from college in a year, it may become even more challenging to maintain strong social connections with people, as modern society dictates that we live relatively independently, spend the majority of our days at work, and have our friends and families largely dispersed over the country and globe. Despite these challenges, I understand that feeling isolated, and the accompanying chronic inflammation and suppression of the immune system, can have long-term impacts. Studies have shown that a lack of social support can serve as a risk factor for cancer development and progression. [5] A prospective study of 10,808 women found that divorce/separation and death of a close relative or friend were associated with increased risk of breast cancer. [6] Increasing levels of social integration are associated with decreased rates of coronary heart disease, better recovery from heart attack and stroke, and even decreased overall rates of mortality, independent of other sociodemographic factors and measures of health status and functioning. [7]

I know that understanding the scientific importance of social connection for my health, well-being, and longevity has helped me to prioritize it the same way I prioritize making time to exercise, sleep, and eat nutritious meals. Sometimes it's hard to think about it in that way because we didn't learn about it in high school health class, but it is really just as, or more, important. In the United States today we have epidemics of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, but also of loneliness, with the number of people reporting that they have no close confidant nearly tripling between 1985 and 2004. [8] There are many ways we can strengthen our social connections, and because research suggests that it is our subjective perception of connection rather than our objective number of social ties that matters, it is important that we go about building our social network in a meaningful way. Thus, the best strategy may not be friending everyone on Facebook and their dog but rather thinking about what really makes us feel close with others. It may involve strengthening connections we already have through heartfelt conversations, weekly lunches, or shooting hoops. It could mean expanding our circle of friends by joining community groups or organizations of people with common interests, or starting our own. Volunteering or community service is also a good way to connect with others. Don't be afraid to reach out to people; we naturally love to connect.

Your health is in your hands -- feel justified and liberated to step away from your computer, your iPhone, and your work, and go spend quality time with your friends and family. In fact, call someone up right now and make plans. It's the doctor's orders.

Keryn Breiterman-Loader is a Stanford University undergraduate Roscow Fellow at the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education.

References:

[1] Cohen, S., W. J. Doyle, D. P. Skoner, B. S. Rabin, and J. M. Gwaltney. 1997. "Social Ties and Susceptibility to the Common Cold." JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 277 (24) (June 25): 1940-1944. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540480040036.

[2] Thoits, Peggy A. 2010. "Stress and Health Major Findings and Policy Implications." Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51 (1 suppl) (November 1): S41-S53. doi:10.1177/0022146510383499.

[3] Uchino, Bert. 2006. "Social Support and Health: A Review of Physiological Processes Potentially Underlying Links to Disease Outcomes." Journal of Behavioral Medicine 29 (4): 377-387. doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5.

[4] Cohen, Sheldon. 2004. "Social Relationships and Health." American Psychologist 59 (8): 676-684. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676.

[5] Antoni, Michael H., Susan K. Lutgendorf, Steven W. Cole, Firdaus S. Dhabhar, Sandra E. Sephton, Paige Green McDonald, Michael Stefanek, and Anil K. Sood. 2006. "The Influence of Bio-behavioural Factors on Tumour Biology: Pathways and Mechanisms." Nature Reviews Cancer 6 (3) (March 1): 240-248. doi:10.1038/nrc1820.

[6] Lillberg, Kirsi, Pia K. Verkasalo, Jaakko Kaprio, Lyly Teppo, Hans Helenius, and Markku Koskenvuo. 2003. "Stressful Life Events and Risk of Breast Cancer in 10,808 Women: A Cohort Study." American Journal of Epidemiology 157 (5) (March 1): 415-423. doi:10.1093/aje/kwg002.

[7] Seeman, Teresa E. 1996. "Social Ties and Health: The Benefits of Social Integration." Annals of Epidemiology 6 (5) (September): 442-451. doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(96)00095-6.

[8] McPherson, Miller, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and Matthew E. Brashears. 2006. "Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks over Two Decades." American Sociological Review 71 (3) (June 1): 353-375. doi:10.1177/000312240607100301.

For more by Project Compassion Stanford, click here.

For more on emotional wellness, click here.