On Friday 20th, two armed gunmen, one a trained Taliban fighter, forced their way into the offices of Peshawar's English-daily newspaper, The Frontier Post, and opened fire with machine guns. As the editorial staff ran for cover, the security guards tried to overpower them. In the ensuing scuffle the Taliban fighter was shot in the arm with his own gun. The two men fled, continuing to pump bullets into the air, even from the seat of their car, before screeching off in a cloud of dust. Peshawar, in the North-Western Khyber region on the edge of the country's tribal areas, has been dubbed the "terror capital" of Pakistan for good reason. According to national news reports, this year alone 129 people have been killed and 279 injured in terrorist-related incidents. Last September 150 were killed in a single week. And all in a place roughly the size of New York City. Ranked 151st out of 178 countries in the 2010 Reporters Without Borders press freedom index, 70 journalists were killed there in 2013 alone, with a statistically higher death rate among those covering politics--like the writers at The Frontier Post.

Jalil Afridi with some of the staff of The Frontier Post The above account is from The Frontier Post's Managing Editor, Jalil Alfridi, a former student at the University of Pepperdine, California. He claims that he was in Islamabad at the time of the shootout, but when his younger brother, Bilal Alfridi, reported the incident to the Peshawar police, he discovered that a similar complaint had already been filed against him and his two brothers. All three were accused of attempted murder and Bilal was slapped behind bars. Says Jalil: "I can prove I was having meetings with my staff in Islamabad when it happened. The police didn't make a single inquiry."

According to Jalil, those responsible for the accusations against him were the very same individuals who had terrorized his offices. "They had the support of drug lords and the property mafia. They exert enormous influence, even over the police."

This, he says, is the current state of the rule of law in Pakistan. The Frontier Post is unique in being the only English-language newspaper distributed widely in both Pakistan and neighbouring Afghanistan. The paper was founded by Jalil's father, the influential and well-connected Rehmat Shah Afridi. Jalil returned to Pakistan from the United States in 1999, when his father was arrested on charges of hashish trafficking--a crime that in Pakistan carries the death penalty. Rehmat Shah Afridi himself claimed that he was convicted for exposing a deal between former Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif and Osama Bin Laden, in which Bin Laden allegedly paid Sharif huge sums of money to support the cause of Jihad in Afghanistan. Working closely with Amnesty International through various appeals, Jalil managed to get his father's sentence commuted to life imprisonment. Jalil had zero experience running a newspaper, which at that time was on the brink of financial ruin and running on the goodwill of a demoralized and skeletal staff. It was just before his 24th birthday. "When I arrived the paper was in ashes. There weren't even any computers or tables. Not even a printing press," says Jalil. "The few staff members who had stayed on hadn't even been paid for six months." He and his older brother, Mahmood, a graduate of London's Huron University, began to learn the business from scratch, with Jalil focusing on the marketing side. "I used to sit in the back seat of my motorcycle with my staff members to meet the marketing heads of leading national and multinational companies," Jalil recalls. "Those were tough times but the staff were incredibly dedicated. We all became close friends and slowly the paper began to grow." The rebuild was not smooth sailing. On January 29, 2001, a letter to the editor appeared in the Post titled 'Why Muslims Hate Jews' that violated federal blasphemy laws. Five employees were charged. The paper, in turn, filed an action against two employees whom Jalil believes were trying to damage the paper's reputation. One of these was Munawwar Mohsin, a man with a history of drug addiction and mental illness. He was convicted of the charges and could have faced life imprisonment, but the judge dismissed the case due to his mental condition. In June 2001, after a six-month closure, the Post was permitted to restart publication. Then came 9/11 and the world media landed en masse in Peshawar, looking for leads on Al Queda and Osama Bin Laden. In one week alone, Jalil spoke to almost 200 international journalists from his desk at the Post. "My hair turned white almost overnight," he recalls.

The paper began to gain an international reputation for quality reporting on geopolitical issues. "American forces based in Afghanistan were only allowed access to the Internet once a week and weren't allowed to use mobile phones in case the Taliban picked up the signals," says Jalil. "They would rely on The Frontier Post to learn about current events." He says the paper also became popular among NATO forces, and the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) the NATO-led security mission based in Afghanistan. Jalil and his brother spent the next thirteen years developing the newspaper, which today has the third largest circulation in the country. The Post now employs over two hundred staff and has expanded beyond Peshawar to operate out of the major urban centers of Quetta, Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad, Jalil continued to work on his father's legal case, and in 2008, Rehmat Shah Afridi was finally released. But it was far from a happy reunion. The stress had taken their toll on his father's psychological health. He began to drink heavily and became increasingly abusive to those closest to him. "One day he slapped me in front of my staff in the Lahore office. On another occasion he brought an Ak47 into the office and dared my bother and I to enter the premises. More than once he shot at my brother's car. He would do crazy things almost every week." "We tried to explain to him that he was no longer in a position to run the newspaper. It's illegal for a convict to run a media outlet in Pakistan. We tried to make him understand that we were now the legal directors and that it was our years of hard work that was making it successful." Around that time, says Jalil, some criminals involved in drugs and terrorism began to influence his father for their own purposes, fueling his instability and paranoia.

His whole life, Jalil had looked up to his father, who in 1984 against all odds had been the first ethnic Pathan to found a media institution--becoming a symbol of pride for the region. "I feel really sad. When your hero turns into villain it's very painful."

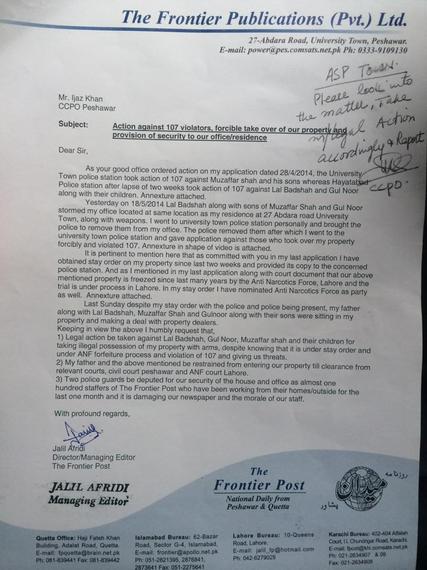

On April 20, Rehmat Shah Afridi held a press conference in Islamabad during which he disowned his wife and his three sons. That same day he informed the Peshawar police stating that he felt threatened by them all. Jalil Afridi appealed to the inspector general of police for an official enquiry to clear his family name. The inquiry concluded that Rehmat Shah Afridi had borrowed millions of rupees from private lenders, signing agreements for his properties in return. This was, in fact, impossible since all his properties had been frozen by the government after the Supreme Court conviction in accord with Pakistani law.

Although the inquiry ultimately absolved Jalil and his brothers from any wrongdoing, some of the private lenders were in close contacts with the Taliban groups in Pakistan, and this is where the story spins out of control. Armed gunmen began to conduct raids on Jalil's house, terrorizing his wife and children. Meanwhile, his father began registering another legal case against his sons over property rights. "Just last week my father went to The Frontier Post's Lahore Office, along with ten gunmen. They kicked out the staff at gunpoint. Two staff members were beaten up and held hostage for two hours."

All the editorial staff turned up at the police station to file a report, and finally won a court order that forbids Rehmat Shah Afridi from interfering with the publication.

But although Jalil has applied numerous times to the authorities for protection for his staff and his family, even providing video evidence of gunmen raiding his home office, he has received no response. The raids on his home made him increasingly fearful over the safety of his wife and his two small boys--four year old Shayan and one and a half year old Abdullah. As a last resort, Jalil requested the federal government for an arms license.

"In Pakistan weapons are as easy as onions to get, but with such a real threat I still haven't received permission."

Jalil is still hoping that the Pakistani government, intelligence agencies and the Supreme Court will arrest and convict those responsible for what he sees as a conspiracy to intimidate his staff and destroy The Frontier Post.

"I am now in fear for my life and that of my family, but I plan to fight till I die," he states.

"I am not going to lay down my beliefs, my newspaper or my soul in front of vultures, drug dealers and terrorists. I will live until my life is written by God."