Richard Roth was born in Brooklyn in 1946. He received his BFA from Cooper Union, and his MFA from Tyler. He is the former chair and current faculty member of the Department of Painting and Printmaking at VCU. He has shown extensively nationally and internationally. His current show at Reynolds Gallery in Richmond includes paintings from the '70s, '80s, and 2000s, and will run until February 28.

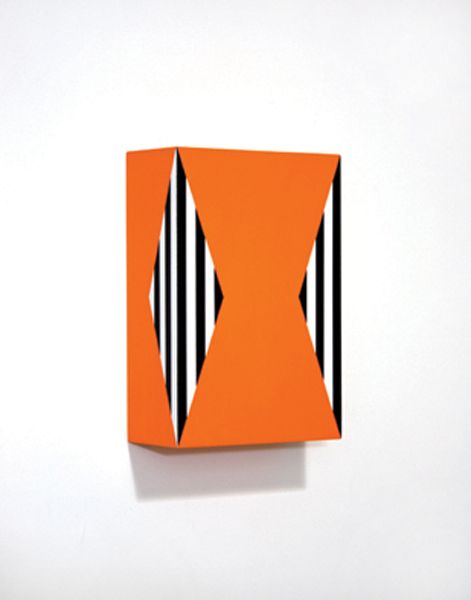

Painter's Block, 2012,

Acrylic on birch plywood panel,

12 x 8 x 4 inches

Ridley Howard: It's very interesting to see work in a gallery show that spans over such a long period of time, that deals with a similar language of painting... but in such different ways. Can you talk a bit about the work in the show?

Richard Roth: Of course, it's a thrill to see the early work and the new paintings together. Bev Reynolds gave me a great opportunity to show the two bodies of work in adjacent galleries. For me, the most important thing about this exhibition involves my changing attitude toward painting. I painted for many years beginning around 1969, then in 1993 for more than 10 years my practice became more conceptual -- creating collections of contemporary material culture. I returned to painting in 2005 with a renewed and revitalized interest, fueled by conceptualism and informed by postmodern attitudes. Now, painting for me is like returning home.

Under the Influence, 2012,

Acrylic on birch plywood panel,

12 x 8 x 4 inches

I love the sense of play, and the slight show of hand, which is unexpected at first glance. Can you talk about how they happen?

The small 3-D polychrome paintings are arrived at in a pretty traditional way, they evolve from the process of their making. I start painting on panels I use as prototypes -- they are identical in size to the final paintings and they are quite roughly painted. I want to develop ideas as quickly as possible and the paintings change rapidly, I often use colored tape to change forms, whatever's fast -- things get messy and I usually just paint one side and the front, just enough for me to understand the painting. When I find the painting, when it's right, I repaint it carefully on a new panel. I don't love this final part of the process -- re-fabrication -- but I believe it is necessary for the idea of the work to be read clearly and without any kind of nostalgic patina. The first step of the process is the party, the second step is what the paintings demand.

As to the "slight show of hand," I see these paintings as humble in their very basic handmadeness. They have to be clean and clear, accurate as they need to be, but no more. I want them to be straightforward, not finish-fetish paintings. The pencil marks and slight deviations in the paint are like the squeaks made by the quick fingers of a musician playing acoustic guitar -- simply natural bi-products.

Interesting to think about work from the 70s' and '80s in relation to the discussion at the time. They seem to have a subversive jabbing humor that is different than the more self-contained spirit of the newer work, like the fire extinguisher in a Malevich-like wall arrangement. Not cynical at all... on one hand, they seem like a celebration of painting, but also maybe play with ideas of painting's death.

So many painters, and artists in general, love functional objects. As Robert Henri said, "They are so beautiful, so simple and plain and straight to their meaning. There is no 'Art' about them, they have not been made beautiful, they are beautiful." We all learn from the straightforward beauty of the functional. In pieces like Fire Chief, I just riffed on those two worlds colliding. I don't think the standard hierarchies of value are very useful today, and I think that attitude is evident in pieces like Fire Chief. Yes, perhaps you're right -- celebrating and mourning painting. I've always loved monochrome painting, but I'm not a believer of its doctrines, so this is my gently subversive monochrome, and when it ignites, the fire extinguisher may just save it.

Fire Chief, 1988,

Acrylic on wood panel with fire extinguisher,

61 ½ x 69 ½ x 5 inches

At one time, Minimalism was the highest of high brow... and now it is no big deal to correlate Judd, say, to Ikea shelving units... or a retail store display. It is a very accessible, middle-brow notion of style. That tension between the grand and the common seems very much a part of your work.

Yes, I like that very much -- the tension between the grand and the common -- Judd and Ikea.

Though I love form and structure in painting, I don't consider myself a modernist strictly concerned with form, you know, the purity of form. I feel naturally aligned with more playful postmodern attitudes, enamored with product and package design, nature, architecture, masks, custom cars and fashion.

Funny, I do see you as a game-player, but the work also feels quite earnest and romantic, or hopeful. Do you think those impulses overlap?

I think I gave up painting for collecting in 1993 because I expected too much of painting. Painting could never live up to what I needed it to be. At that time, I decided to steer far from painting, and instead study and learn from the world, the endlessly amazing world, through making collections. Anthropology teaches us that all activities and artifacts express a culture, not just the "highest" -- quotidian customs and rituals are as significant as exalted religious ceremonies. I love custom cars, fashion and the culinary arts, but in 1993 I was embarrassed by the pretentiousness of my own culture -- painting. It wasn't until I could see painting as just another subculture, not as the culture, not as high culture, that I could re-enter it with full enthusiasm and without cynicism. I can't imagine a serious painter today who doesn't have a love/hate relationship with painting. Doubt and certainty, playful engagement and tedium, breakthroughs and deadlock all coexist in the studio (as in life) and contribute to making simple gestures -- rich carriers. I believe, the poet James Dickey wrote, "love-hate is stronger than either love or hate."

Do you think the limitations of the format -- four-inch box, paint, shape -- are actually liberating? I always liked Hickey's essay about basketball, rules of the game being necessary for creative freedom.

I think making art should be a no-holds-barred activity, but, now for me, my self-imposed limits have released a flood of new and unfolding ideas. It has been a little over six years since I began my current body of work -- the 3-D paintings. When I first began making them, I was immediately excited but thought, "they are so small, so reductive, I will make five and run out of options." What resulted was quite the opposite -- every new painting suggested a dozen new avenues.

Untitled (yellow corner), 1971

Enamel paint, glass

72 x 72 inches

The full-length interview can be read at BurnAway.Org.

Work from the show can be seen at www.reynoldsgallery.com/