A few weeks ago, I saw the New York premier of The Reckoning at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival. The crowd was quite astonishing. Two of the International Criminal Court prosecutors featured in the film, Christine Chung and Fatou Bensouda, were in attendance. The top brass from Human Rights Watch were also present along with a prosecutor from the Nuremberg trials. When Pamela Yates, the director, introduced him he received a standing ovation.

The film was stark and penetrating. It discussed the worst war crimes and crimes against humanity of our time, but did so in a rational, rights based justice context. The main character in The Reckoning is the International Criminal Court itself. Founded in 2002, its mandate is to try the perpetrators of crimes that have been committed since the court's inception. A stipulation exists that the court may only make cases against member states, unless the UN Security Council has referred them to mount an investigation.

The ICC is based on a treaty, when a country signs on to the treaty, it formalizes its stand against impunity, and renders its citizens eligible for potential investigation. However, the process requires the court to be a last resort only applied if a country proves unable or unwilling to try its own perpetrators. Over 100 countries have signed on to the treaty, but the United States, China, Russia, and Iraq have all refused to do so.

Since its founding the ICC has made cases against the leaders of the Lord's Resistance Army in Uganda, war lords in the Congo and the people with the most responsibility for the Darfur genocide, including Al-Bashir, the president of Sudan. They have also built a preliminary case in Columbia against paramilitary leaders and the corrupt members of government who support them.

Beyond simply detailing the court's process, The Reckoning provides a compelling portrait of those who wage the struggle for global justice. I caught up with director Pamela Yates to discuss the film, which will screen tomorrow on POV.

Robyn Hillman-Harrigan: Hi Pamela, first of all I'd like to thank you for the important work that your film does. Shifting perceptions and educating people about Human Rights advocacy is vital. What exactly sparked you to engage with the topic of the International Criminal Court and how did you gain so much access to the subjects in the film?

Pamela Yates: The idea for The Reckoning came to me in a remote village high in the Peruvian Andes, while shooting my last film, State of Fear: The Truth About Terrorism. The film is based on the findings of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission. One of the truth commissioners told me that he had formerly worked at the Coalition for the International Criminal Court (CICC) trying to establish the first permanent, international court to try perpetrators of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. It was 2002 and the ICC was just beginning. I was fascinated that 120 countries had come together to build this new court, and that most of the world was not even aware of its existence.

Access is a matter of time and trust. It took us 3 years, across 4 continents to get the story of The Reckoning just right. We had the time to build relationships and we even made 2 short prequels to The Reckoning, which are on the web called Demons and Dreamers and Building Justice. This proved that we were serious about artistically communicating ideas of international justice.

We also invited outreach partners to join our Board of Advisers during the making of The Reckoning -- like Human Rights Watch, the International Center for Transitional Justice, Amnesty International and Facing History and Ourselves -- because ideas about transitional justice and human rights can be quite complex and we needed their expertise. This gained us respect with the ICC. The other factor was that the prosecutor and his team saw us going into conflict zones to try to film the scenes of the alleged crimes that they were prosecuting. This gave us common ground.

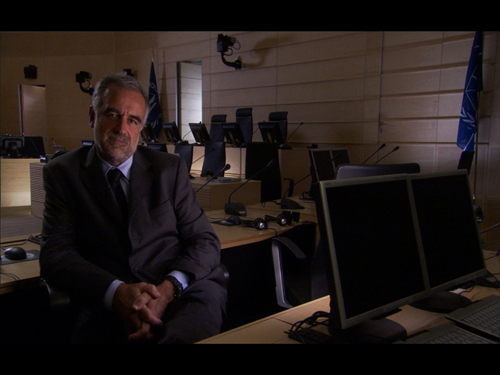

ICC prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo

Robyn: Some people are not aware of the role the International Criminal Court plays, your film gives a great overview, but could you discuss further the formation of the court back in 2002? How did it came into being and what opposition has it faced?

Pamela: We are actually producing short educational modules to address this question from additional material that we filmed, and the first 2 will be up on the web for our national PBS broadcast on July 14, 2009.

Because there is an untold story of the role of civil society, non-governmental organizations from around the world who worked tirelessly for years preparing for the Rome Conference where the Rome Statute, the treaty that created the ICC was affirmed by 120 countries in 1998. Even for the creators, it was thought that it would take another 10 years before at least 60 countries would ratify the Rome Statute and the International Criminal Court could come into existence. But again, the Coalition for the International Criminal Court swung into action and within 4 years 66 countries had ratified the Statute and the ICC was born. That day, July 17th, has now been officially named International Justice Day.

Robyn: Can you speak a bit about what your involvement with the Human Rights Watch film festival has been over the years and about the festival in general?

Pamela: For the kinds of films I make, the Human Rights Watch International Film Festival, is the pinnacle. Because it combines human rights storytelling with a keen eye for cinema. And the festival programmers carefully choose the films from around the world with that criteria. Beyond the festival itself, people around the country and the world look at their selection on their website for ideas to program and broadcast compelling films. And in the past 20 years since the festival began, dozens of human rights film festivals have sprung up around the globe who have been inspired by their example and who have formed the Human Rights Film Network.

This is our 4th film in 20 years at the festival.

Robyn: The early opposition the ICC received from the U.S. government under Bush is touched upon in the film. Can you elaborate on how they sought to pressure other countries not to join? Additionally, could you clarify the process of being tried by the court? Only citizens of member states can be prosecuted, without a referral from the UN Security Council, correct?

Pamela: In The Reckoning we explore the 2 ways the United States has related to the ICC. One is the multilateralist approach, that celebrates our 200 years of jurisprudence and recognizes the US contribution in the writing of the Rome Statute as well as the US contribution to international justice from Nuremberg though the Yugoslav and Rwanda tribunals. The other, is the unilateralist approach articulated in The Reckoning by Bush's former UN Ambassador John Bolton. Bolton unabashedly states that the US should fight the Court, by actively convincing other countries to sign side deals with the US, like the Bilateral Immunity Agreements (BIAs).

There are 3 ways a case can be initiated: A member country that is unable or unwilling to try suspects can refer the case to the ICC (as in Uganda, the Congo and the Central African Republic); the Prosecutor can open a case independently as long as the crimes occurred in a member state or by a national of a member state (this has not happened yet); and finally the UN Security Council can refer a case in a country that is not a state party to the ICC (as in Sudan).

Robyn: The ICC has boldly put out an arrest warrant for the president of Sudan because of his role in the Darfur genocide. Do you think it will lead to his eventual arrest, and is it likely that ICC's enforcement abilities will improve?

Pamela: Having no police force or way to arrest perpetrators of these grave crimes is a recognized weakness of the ICC. So the international community must decide how this aspect can be strengthened. At the ICC review conference in 2010 in Kampala I'm sure this will be high on the agenda.

Twelve ICC arrest warrants and one summons have been issued to date, 4 people are in custody in The Hague, the first trial is underway. And the arrest warrant for the President of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir has thrust the Court onto the world stage. When I began The Reckoning, I thought the film was going to be about arrests and trials, but I gradually came to understand that the real story was the effect the ICC was having in the world. The ICC has loudly declared that no one is above the law and the world is taking note.

Robyn: The Reckoning depicts some of the worst war crimes and crimes against humanity, but does so in a way that allows audiences to rationally understand the history, while also emotionally grasping the tragedy. How did you achieve this balance?

Former Child Soldiers

Pamela: I worked with editor Peter Kinoy and Producer Paco de Onís to make a film for general audiences both here and abroad who had never heard of the ICC. Peter was brilliant about how to fashion the narrative around the essentials of international justice, while consistently hooking the audience by telling at times a hopeful story, at times a harrowing one.

I insist on working with all the filmic tools -- carefully thought out cinematography that is beautiful, sad, epic; unifying music throughout the film that captures the emotional highs andlows, well written narration spoken by a soulful narrator, and always an emphasis on the victims and survivors at the center of this justice initiative. I believe that the most beautiful panorama of cinema is the geography of the human face, which is why there are so many close ups of faces in all my films.

The audience feels like they are watching a movie rather than a news report, and I always show a way forward because I am an idealist. So while there may not be a happy ending, thereis a bittersweet ending.

Robyn: How does The Reckoning tie in with your past film projects, and where in this framework will your next film fit? Can you give us a preview of what's to come?

Pamela: State of Fear (2005) was about the Peruvian Truth Commission. TRUTH. The Reckoning (2009) is about the International Criminal Court. JUSTICE. and to come will be a film about historical and collective memory titled The Future of Memories. MEMORY. So this is actually a trilogy: TRUTH, JUSTICE, MEMORY.

Right now I'm finishing a new film which is the sequel to the very first film I made, When the Mountains Tremble (1983). When the Mountains Tremble is a film about social revolution in Guatemala in 1982, when the state rose up and committed genocide, killing 200,000 mostly Mayan Indians. Arrest warrants have been issued to 6 Guatemalan generals and police officials, 2 of whom are in my original film. The prosecution has asked us to go back into all our filmic outtakes from Mountains to be used as forensic evidence in the genocide case being tried at the Spanish Audiencia Nacional, the same court that had Pinochet detained in London in 1998. In another eerie twist of fate, the storyteller in Mountains was Rigoberta Menchú , the Nobel Peace Laureate. It was Rigoberta that brought the case to the Spanish Audiencia Nacional . So there characters that travel across 25 years of Guatemalan history to tell a multi-generational story. I will also explore how documentary filmmaking makes a difference, so it's meant to inspire emerging filmmakers to get interested in human rights themes. The new film is called Granito -- the tiny grain of sand we can each contribute.

Robyn: Is there anything else you would like to add?

Pamela: I would like people to know that The Reckoning is a political thriller about international crime and punishment. And after 90 minutes on the edge, you will have learned a huge amount about an inspiring and hopeful new global justice institution. But the ICC is a beleaguered institution that needs our help. And as global citizens we can join in the conversation, engage in the debate only when we are informed. And that's why we've also conceived a 3 year audience engagement and outreach campaign so that The Reckoning can be the flagship film, and by taking people on an emotional odyssey can then lead them to get involved with the international justice movement. Check out our outreach campaign at international justice central.

I also want to say that I work with a team of people, Paco de Onís, the Producer and Peter Kinoy, the editor. The Reckoning is a film by the 3 of us because we conceive of the ideas together and work from conception through the outreach phase, contributing. Peter and I founded Skylight Pictures more than 25 years ago with a focus on making films about human rights and the quest for justice.

Robyn: Thank you very much for your time.