I believe that Diego Rivera's and Frida Kahlo's frescoes, currently at the Detroit Institute of Arts and Jean Michel Basquiat; The Unknown Notebooks, currently at the Brooklyn Museum since last Friday, are examples of a curatorial trend in which the life of the artists is transformed into the source of artistic value of the art displayed. This, of course, diverts the focus from the art object to those things that, allegedly, inspired those works of art. This means that we are looking at the art of the past with the spectacles we use to justify art fair prices these days.

A couple of years ago in Art Basel, I asked a very important collector about his favorite artist. He mentioned an Asian artist whose name I do not remember. He builds barges with the wood recovered from wrecked fishing boats found in the shores of the Pacific island where he comes from. So, in his case, the source of artistic value does not lay in the art object's "form," but in the "hardships and pain" that the materials used allegedly, contain. This is not very different to the way relics used to function a few hundreds of years ago.

Filling several galleries at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit coalesces around a masterpiece that is part of the Detroit Institute's building.Detroit Industry is an idealized ode to the city in 27 frescoes. These formed the project that brought Diego Rivera, one of the three best known Mexican muralists, to Detroit in April 1932, accompanied by his much younger wife, Frida Kahlo, also an artist.

Over the next 11 months, Rivera researched, designed and painted the frescoes that cover the four vaulting walls of the museum's courtyard, now known as the Rivera Court. It features heroic scenes of muscular workers and even more idealized earth mothers grasping sheaths of wheat or armloads of fruit.

Frida Kahlo's time in Detroit was painful and, from a visual perspective, his work has nothing to do with the monumentality of his husband's masterpiece. When she arrived, she was well along in synthesizing the influences of Mexican folk art and surrealism into a mature vision. But in many ways, the miscarriage she suffered while in Detroit spurred the searing form of self-representation that is her contribution to art history.

This miscarriage was the second physical trauma of her fraught, intensely creative life, the first being a near-fatal traffic accident in Mexico City in 1925, which caused her continual pain for the remainder of her life and severely reduced her chances of having children. Thus, this show is only interesting from the point of view of the reconstruction of the context in which Rivera's mural (so important for the city of Detroit) was produced.

That is why Roberta Smith is right to point out in her New York Times piece that "the 70 works included in the show form a kind of contest between a hefty hare and tiny tortoise. Rivera takes up most of the room -- as, tall and bulky, he did in real life -- but Kahlo emerges in the final galleries as the stronger, more personal and more original artist." However, I wonder whether this is a fair assessment of the showing. Do we need a show to know that Frida Kahlo's works are more personal? Is it better art because is more personal? Is it relevant to show a political artist along an existential surrealist? It is as if contemporary taste privileged that inversion of the low over the high where the underdog or the "small" and "flawed" becomes "art."

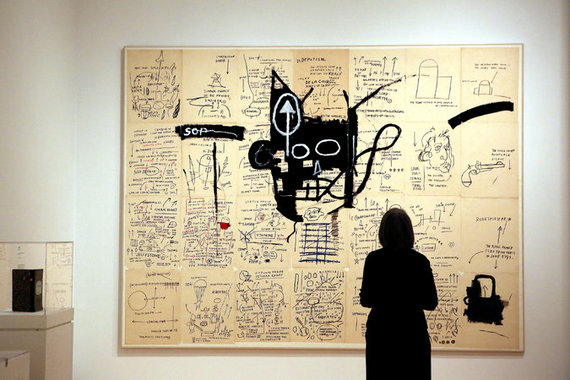

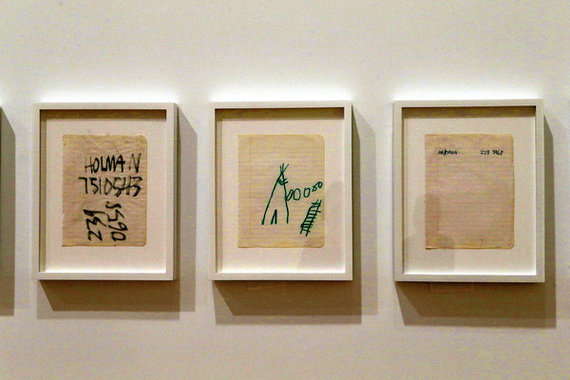

Something similar happens with Basquiat's show at the Brooklyn Museum, which is built around 160 pages from eight notebooks in the collection of Larry Warsh. The show holds no startling revelations -- the notebooks are "unknown" only in the most literal sense that they have never been exhibited before. But they confirm the centrality of language and hand lettering to Basquiat's art in new detail. Organised by Dieter Buchhart, an independent curator and Basquiat specialist working with Tricia Laughlin Bloom, a curator at the museum until December, this show displays the notebook drawings in long rows in low-slung vitrines or on the walls, are supplemented by about 30 other works: drawings of several kinds (including a fabulous one involving a triangle filled with words and symbols, 10 feet across) and a handful of works on canvas that demonstrate how language was carried over into painting. Basquiat began by collaging canvases with scores of drawings or color photocopies of them, and then adding larger images, like the black mask-skull on an untitled work from 1982-83, a griot surrounded by a swarm of words.

The show considers that Basquiat's decision not to write or draw on the backs of the pages automatically transforms them into autonomous works of art. To make things even worse, in the exhibition's catalogue, Buchhart considers this "notes-cum-drawings-cum-artworks" as examples of "concrete art." I understand his scholarly excitement when working with the notebooks of his favorite artist. The problem, however, is that it ends up unnecessarily injecting meaning to an already magnified aspect of Basquiat's work, and I wonder whether this doesn't follow the aforementioned mechanic of inverting "the low over the high" in order to justify the over-inflated value of contemporary artworks. Just a thought.