This year marks the 25th anniversary of China's national protest movement of 1989, and, of course, also of its subsequent suppression. In the U.S., these events are being commemorated with news coverage as well as important, timely book releases.

In China, meanwhile, where talk of "6.4" (shorthand for the massacre) is intensely censored at even the most normal of times, the coming anniversary is being marked with quiet damage control -- no polemical propaganda, but instead the low-key disappearing of those whom authorities view as likely to make a scene. The recent arrest of the fearless, baritoned rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang stoked a flurry of quickly-deleted expressions of outrage online. Yet far from calling Pu a dangerous subversive, official comment so far has been relatively mild and indirect (ch).

It would have been hard to predict the current tactics of quiet intimidation during the noise of the crisis itself. In late April 1989, when Party leaders stopped viewing the peaceful protestors in Beijing as no more than to-be-ignored "mourners" for the recently-deceased reformist icon Hu Yaobang, the new hardline position was taken suddenly, decisively, and, to a seldom-appreciated extent, in full view of the public.

It's widely accepted that one of the most crucial turning points in radicalizing the conflict was the publication of the April 26 People's Daily editorial "It Is Necessary to Take a Clear-Cut Stand Against Disturbances." Composed and sent for publication (and to be read aloud via nationwide TV and radio broadcasting) after Party conservatives convened a special Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) meeting on April 24, when soon-to-be-ousted reformist leader Zhao Ziyang was abroad, the position staked out in the editorial effectively made negotiation impossible.

Later, when Prime Minister Li Peng met with protestors in May, the document's harsh tone (many point to the word translated "disturbances" or "turmoil" -- as I write below, I think there's more going on) was one of the main points of outrage brought up by the students. According to some, the editorial had actually further inflamed protests just when they were dying down. Yet just how was it possible for one short missive to both incite such resistance and mobilize its suppression?

Friends and Enemies

In his memoirs smuggled out while under house arrest, Zhao Ziyang later wrote that, with the PSC meeting of April 24, Li Peng and other conservatives had succeeded in having the protests deemed an "organized and carefully plotted political struggle." This was carefully chosen, and even fateful language. It's my view that once the word "struggle" (douzheng, 斗争) was deployed by the PSC, the students became enemies of the Party. The subsequent editorial, which used the word four times, and ended with a call for all Party members and PRC citizens to "douzheng to resolutely and swiftly halt this turmoil!", cemented this fact.

As has been noted by many who've studied political crackdowns throughout PRC history, such campaigns are almost always associated with the word douzheng. In his recent book An Anatomy of Chinese: Rhythm, Metaphor, Politics, Perry Link writes that "the word douzheng originally means 'struggle,' so it might not seem entirely a euphemism. But we should view it that way, because [of] the intensity and variety of the cruelty involved." More specifically, Professor Link is writing here about the formulation "class struggle," especially as utilized during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

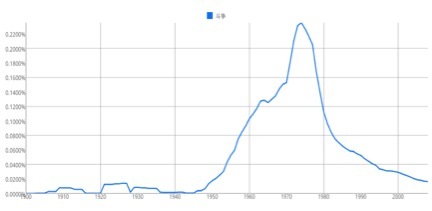

I agree that the implications of the term douzheng were hugely influenced by the Cultural Revolution, but I would also suggest that its pragmatic, official usage shifted importantly after that chaotic period. As the Party's central leadership reasserted control throughout the 1980s and afterwards, the term's frequency of use in public discourse fell extraordinarily. A Google Ngram search shows the steep decline, as reflected in a large corpus of scanned books and periodicals.

Douzheng's frequency of use, as percentage of total "2-grams" appearing in Chinese texts published between 1900-2010. The spike overlaps with the Cultural Revolution.Where the term did continue to be central, however, was in the realm of security and social control. Taking off from one of the core concepts in the work of the German legal theorist Carl Schmitt, University of London Professor Michael Dutton has written with great insight on recurring "friend-enemy" dynamics as the key to the Party's entire political modus operandi. As Mao himself said in 1926: "Who are our enemies, who are our friends? That is a question germane to the revolution."

Douzheng's frequency of use, as percentage of total "2-grams" appearing in Chinese texts published between 1900-2010. The spike overlaps with the Cultural Revolution.Where the term did continue to be central, however, was in the realm of security and social control. Taking off from one of the core concepts in the work of the German legal theorist Carl Schmitt, University of London Professor Michael Dutton has written with great insight on recurring "friend-enemy" dynamics as the key to the Party's entire political modus operandi. As Mao himself said in 1926: "Who are our enemies, who are our friends? That is a question germane to the revolution."

By the post-Cultural Revolution era, when the Party's security apparatus dragged out the term douzheng to publicly label someone, it was clear to everyone on which side of the line they fell.

Doing Things with Words

One of the great milestones in 20th century China scholarship was a book by Michael Schoenhals called Doing Things with Words in Chinese Politics. Generally applying the linguistic theory of "performative utterances," he found that careful wording choices were often used in the Party to signal -- or to create -- important power relationships.

Applying the insights of Schoenhals and of Lucien Pye, an early doyen of American studies on Chinese politics, the security theorist Juha Vuori has advanced the scholarly view that "words in China are not only political objects, but loyalty tests in a system defined by inter-factional struggle." Repetition is allegiance and solidarity.

This was displayed most ironically when Mao's former right-hand man Lin Biao was suddenly condemned at the height of the Cultural Revolution: one of the main charges against him was that he had attempted to promote "unity," in contradiction to Mao's core teachings. An essay in the Peking Review, March 22, 1974, summed up Lin's crimes: "The Philosophy of the Communist Party Is the Philosophy of Struggle [douzheng] -- Refuting Lin Biao for Peddling Confucius' Doctrine of the Mean."

But perhaps nothing is more revealing than the way that douzheng was even transformed grammatically over the course of the Party's many political campaigns. By the late Cultural Revolution era, it became common to hear that someone "had been struggled" (bei douzheng). Needless to say, this phrase would have been perfectly meaningless in the pre-PRC era. By the 1980s, it was instantly understandable throughout China -- calling up images of "struggle sessions."

Parading douzheng targets through the streets is not as in vogue as it once was, but groups against whom the term is used in a high-profile fashion do still find themselves harshly suppressed and forced to publicly recant. The Tiananmen protestors were one such group; ten years later Falun Gong became another. Most recently, the term has been incorporated into a newly hyped-up phrase, "public opinion struggle" (yulun douzheng). Is it a coincidence that this terminology was rolled out at the same time that once-tolerated liberal commentators and civil society activists are being targeted with newly harsh sanctions and intimidation?

Those who were involved in the Tiananmen protests are, for the most part, no longer "enemies" -- they were defeated, after all. As the current deployment of douzheng and its ramifications in arrests and intimidation make clear, the potential enemies today are those who wish to talk about Tiananmen, or similar acts of repression. For today's Party, just like the one of April 26, 1989, language is action.