Fewer and fewer women are choosing to count calories or follow restrictive diets. And they're feeling better than ever because of it.

By Gabrielle Glaser, SELF

When Mallory Gibson, 29, moved to New York City after college to work as a financial analyst at an investment bank, she soon found herself grinding out super stressful 14-hour days. She ate takeout at her desk most nights--and, not surprisingly, put on a few pounds. Although she'd been a healthy-enough eater at college in Austin, Texas, where she'd grab meals at the flagship Whole Foods, now she turned to juice fasts to manage her weight. Her type A drive served her well. "Everyone else was like, 'I can't do it more than a day!' and I'd be on day five," she recalls. But often, when she'd finish, she'd find herself going out with friends and "eating badly, drinking too much wine."

The pattern was physically and emotionally exhausting. "It wasn't sustainable--and I realized that I needed to stop being so restrictive," says Gibson, who was reminded of how, while she was growing up, her parents and brother had cycled between Atkins, Nutrisystem and other regimens. Ironically, it was when she tried Whole30, an anti-inflammation plan that calls for cutting out and reintroducing certain foods to see how your body responds, that the lightbulb went on. "For the first time, I started paying attention to how foods made me feel," she recalls. "And I learned that I want to eat things that make me feel amazing."

Today, Gibson, who works at a hedge fund, eats virtually everything--in moderation, as long as it doesn't make her sluggish (too much cheese) or foggy before a big day (too much wine). She applies the same mind-set to exercise--using ClassPass to mix it up--which for years had mainly been a vehicle for calorie shedding. "The motivation isn't that I want to burn 700 calories a day. It's that I want to feel really good," she says. "It's a totally different value proposition."

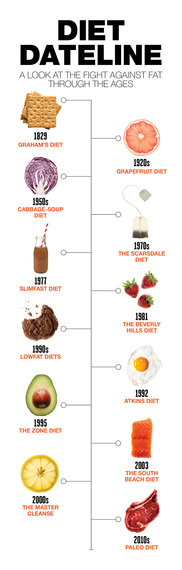

Although food trends and body ideals come and go, one thing has always held true: Some women will sacrifice their health and happiness to be thin--from swallowing diet pills to scarfing gallons of cabbage soup. But a funny thing happened as the food revolution turned chefs into celebrities, farmers' markets more than doubled in number and avocado toast took over the Internet. The percentage of women who say they're dieting has fallen by a third over the last two decades. To many, the very notion of eating diet foods seems sort of old-fashioned--a relic of crazy habits people acquired before they knew better about what their bodies needed.

"My mother and sister did the diet thing, and I saw where it led them. If it's all about 'I want to fit into this dress,' it's not going to last," says Lottie Bildirici, 21, a Brooklyn, New York-based triathlete and recipe developer whose site, Running on Veggies--a bounty of whole-food recipes like grilled peaches over kale and quinoa pizza crust--draws nearly 40,000 Instagram followers. "If you're eating junk and chewing gum all day, you're not going to be able to perform the way you want to if you're going to SoulCycle or a boot camp class," she continues. "Today, it's all about what food can do for you. Strong is the new thin."

Admittedly, adult obesity in America still hovers above 30 percent. But more Americans than ever are telling pollsters they're trying to eat healthier, more balanced food. One casualty? The weight loss industry. For most of the past five years, two of the country's best-known dieting programs, Weight Watchers and Nutrisystem, reported declining revenues. Sales of low-calorie frozen dinners are plunging (meanwhile, butter consumption has increased by almost 25 percent in a decade). Even diet books are lagging. "People aren't really interested in those 'lose 5 pounds in five days' books anymore," says Sarah Passick, an NYC literary agent. "They're looking for a more sustainable approach. Women want to focus on eating a healthy, whole-food diet rather than obsessing over calories. They want to play an active role in their own health, and to think for themselves."

Passick's comment underscores one of the most remarkable aspects of this shift: A casual fluency in food's health benefits has a new kind of cachet. Yes, there's still plenty of misinformation out there (ahem, glutenphobes), but researchers are encouraged by the trend, brought on by the rapid advance of food science. "I'm cautiously optimistic that a younger generation of Americans is becoming more educated about the nutrients they need," says Eric Rimm, Sc.D., professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Gibson, for instance, says she's attuned to what a food can do for her. She'll snack on a pear because it's high in fiber and water, or have an omelet when she brunches with friends after their favorite TRX class to meet her protein quotient. Checking into how meat was raised or produce was grown is about as normal today as it was for old-school dieters to tabulate calorie counts. Darya Rose, Ph.D., a 35-year-old neuroscientist and author of Foodist, as well as the blog Summer Tomato, says the new mind-set is partly a reaction to the unimaginative, industrialized products Americans consumed unquestioningly for so long: "We've rediscovered foods that used to be totally unappealing."

Marissa Ronk, 29, an attorney in Denver, describes how she buys only full-fat dairy--no skim milk, no lowfat cheese--in spite of the slow-to-catch-up USDA dietary guidelines, which still steer consumers toward lowfat options. "First of all, full fat tastes amazing," Ronk says. "Second of all, research is showing that dairy fat isn't as bad for you as once thought. With the real thing, you'll actually eat less and be more satisfied with what you're consuming."

She's right about that, and Ronk's point actually gets at a key reason why an entire generation of dieters before her struggled with their weight. In her recent book The Big Fat Surprise, journalist Nina Teicholz argues that decades of nutrition guidelines favoring lowfat diets had disastrous health consequences. Not only did it turn out that replacing supposedly harmful saturated fat with sugars and vegetable fats became a much bigger risk factor for heart disease and obesity, she says, but chronic lowfat dieting gave American women an unhealthy relationship with food. "When you restrict calories, your metabolism slows down," Teicholz explains, "and in the long run, this makes you more likely to regain weight."

As anyone who's ever been on a diet knows, restriction backfires in another way: It causes you to obsess about the very food you're trying to avoid. Traci Mann, Ph.D., professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota and author of Secrets From the Eating Lab, notes, "When you've been dieting, even looking at food gives you a stronger dopamine rush." The aim for successful weight management, she says, is to make it easier to choose healthy food--without cutting out anything.

The good news is that so many of us are already there. Dopamine--the "feel-good" neurochemical--is essentially what our brains are bathing in as we swipe though the Technicolor cornucopia of Instagram feeds and Pinterest recipe boards. But our synapses fire as much for that glistening lacinato kale salad or barley tossed with shaved golden beets as they do for cake. A picture is worth 1,000 words, especially when those words have traditionally carried the scolding tone of "Eat your vegetables."

Australian fitness phenom Kayla Itsines is a master of this form--her posts of jewel-toned smoothie bowls crowned with fresh fruit can garner more than 50,000 likes, often rivaling the numbers on her super fit selfies. Itsines says she wants women to know that they don't have to restrict any foods if they feel good eating them; she herself eats "from all five food groups, because that is the best way to fuel my body to have the energy it needs." She's a proponent of this new kind of food-positive attitude that makes you want to kill it in your workout--not to cancel out last night's burger and beer, but to reward yourself with, say, a nourishing bowl of spinach and avocado salad. And like many others in her world--author Ella Woodward of Deliciously Ella, Love & Lemons blogger Jeanine Donofrio, the Tone It Up girls--she does it by stirring up a contagious positivity, creating a community in which "women encourage and motivate each other on their healthy lifestyle journeys," as Itsines puts it.

Research shows you're likely to eat healthier if your friends do, too. And so the Web has become a virtual communal table, where good food brings us a little closer to one another, making us aspire to better versions of ourselves. Andrea Baumgartner, 23, a community manager and a copywriter at an NYC advertising agency, says she regularly logs onto Pinterest to see what her foodie friends are up to. "My roommate is opening a farm-to-table restaurant, and I love seeing what the chef brings back from the farmers' market," she says. "Another friend is obsessed with açaí bowls. I also have friends who post their baking adventures, which gets me excited to bake something with alternative ingredients. When I see what my friends are doing, I'm more motivated to do it myself."

Lack of motivation--specifically, sustained self-motivation--was arguably what doomed generations of dieters to fail. It's hard to find a higher calling only in pounds lost or in inches no longer pinched. You can imagine Jean Nidetch, who founded Weight Watchers in 1963 and recently died at 91, cheering at the news that so many women now crave the healthy foods that the program tried to get them to eat with controlled portions and precounted calories; by incentivizing them with points, not pleasure.

And it's precisely because women are making their own food decisions--cooking for themselves and wanting to feel their best after every bite--that they're finally winning the diet wars. "Eating well is about self-discovery, knowing what your body needs and making changes to fit that," Baumgartner says. "I don't think I could actually ever do a diet. I love food too much."