This is the first installment of a four-part series chronicling singer-songwriter and producer Shawn Amos' childhood in 1970s Los Angeles.

The 7000 block of Sunset Strip was a stretch of storefronts dedicated to vice. Head shops, sex shops, liquor stores, and fast food were all clustered together. You could shop for a bong, a forty-ounce, a dildo, and a bucket of fried chicken without ever crossing the street. On the south side of the block, the drab Hollywood Studio Inn Motel and the gaudy Saharan Motor Hotel bookended the Seventh Veil -- a strip club with an Ali Baba facade and purple-and-pink neon lights pulsing "LIVE NUDE GIRLS" in perfect 4/4 time. The motel rooms were in constant turnover by the streetwalkers and tricks who were virtually the only pedestrians. Police cars patrolled but rarely made an arrest. Instead, the cops and hookers engaged in a requisite flirtation, giving each other a brief respite from their stressful days. If the rules were written differently, they'd probably be friends, lovers, or customers. Maybe they were. But regardless, the cops and hookers relied on each other, the only other citizens who were dependable.

Their curbside exchanges had more the feel of a campus exchange between classes rather than a vice squad shakedown. I never saw a hooker get busted my entire childhood except on TV shows. The hookers I knew in Hollywood were maternal figures. I got to be friendly with them as I rode my bike back and forth from home. They spoke to me on street corners while I waited for the light to turn green, calling me "sweetie" and "honey," asking me what I was learning in school. Hookers were the opposite of my mother. They were strong, predictable. They seemed to operate by a firm set of rules. I looked forward to seeing them -- something short of a boyhood crush. I longed for the feeling of safety and security they seemed to convey.

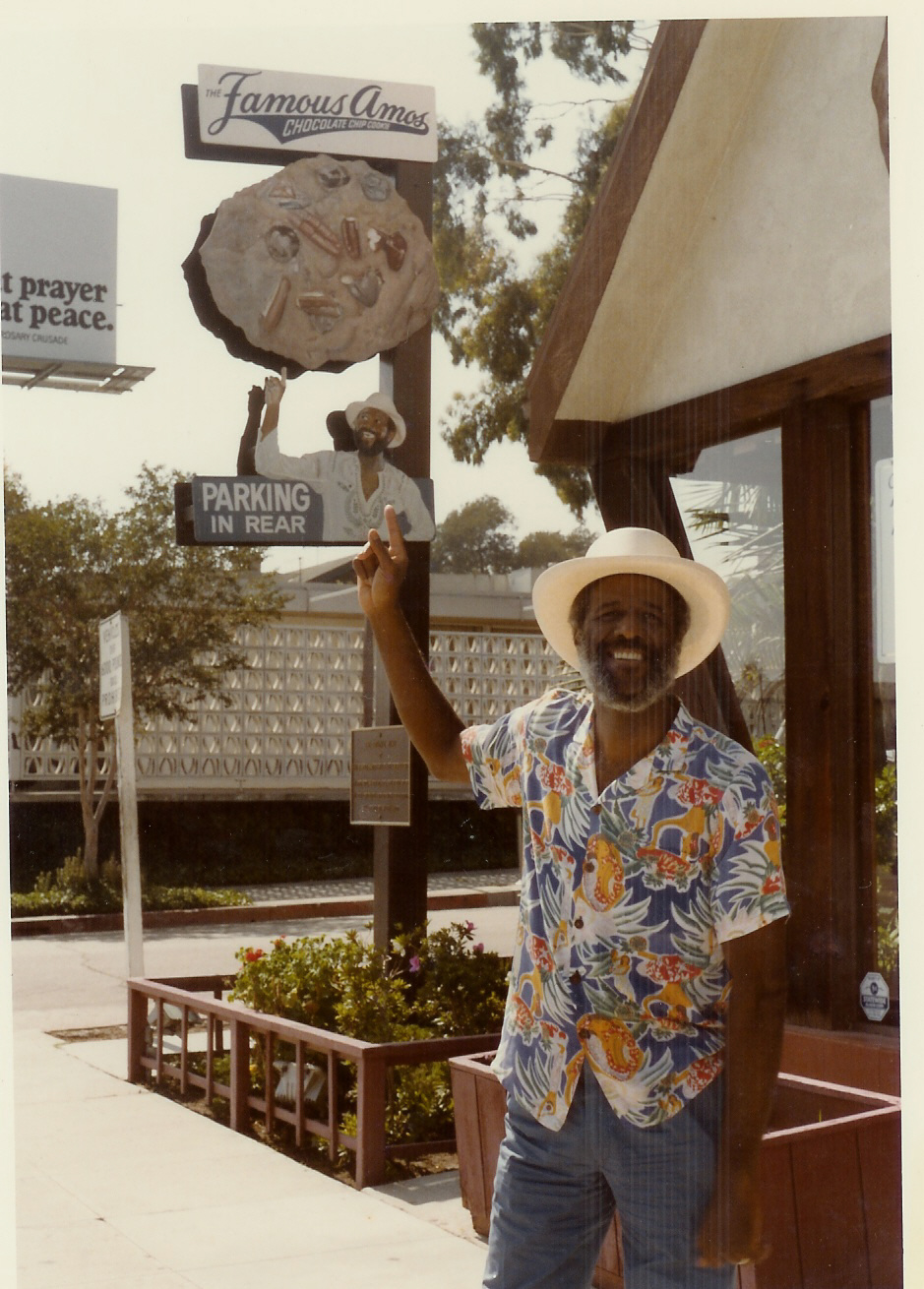

On the north side of the same block, directly across the street from the Seventh Veil, was an empty storefront. An A-frame building with large glass windows and empty flower boxes. It sat on the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Formosa Avenue, just three blocks from the A&M Records lot where my father had worked and 11 blocks from my house. It occupied the geographic center of my Hollywood universe. It looked quaint in a way the other stucco, flat-roofed buildings on the block did not: The A-frame store at 7181 Sunset Boulevard belonged on Main Street. It looked like a zoning mistake.

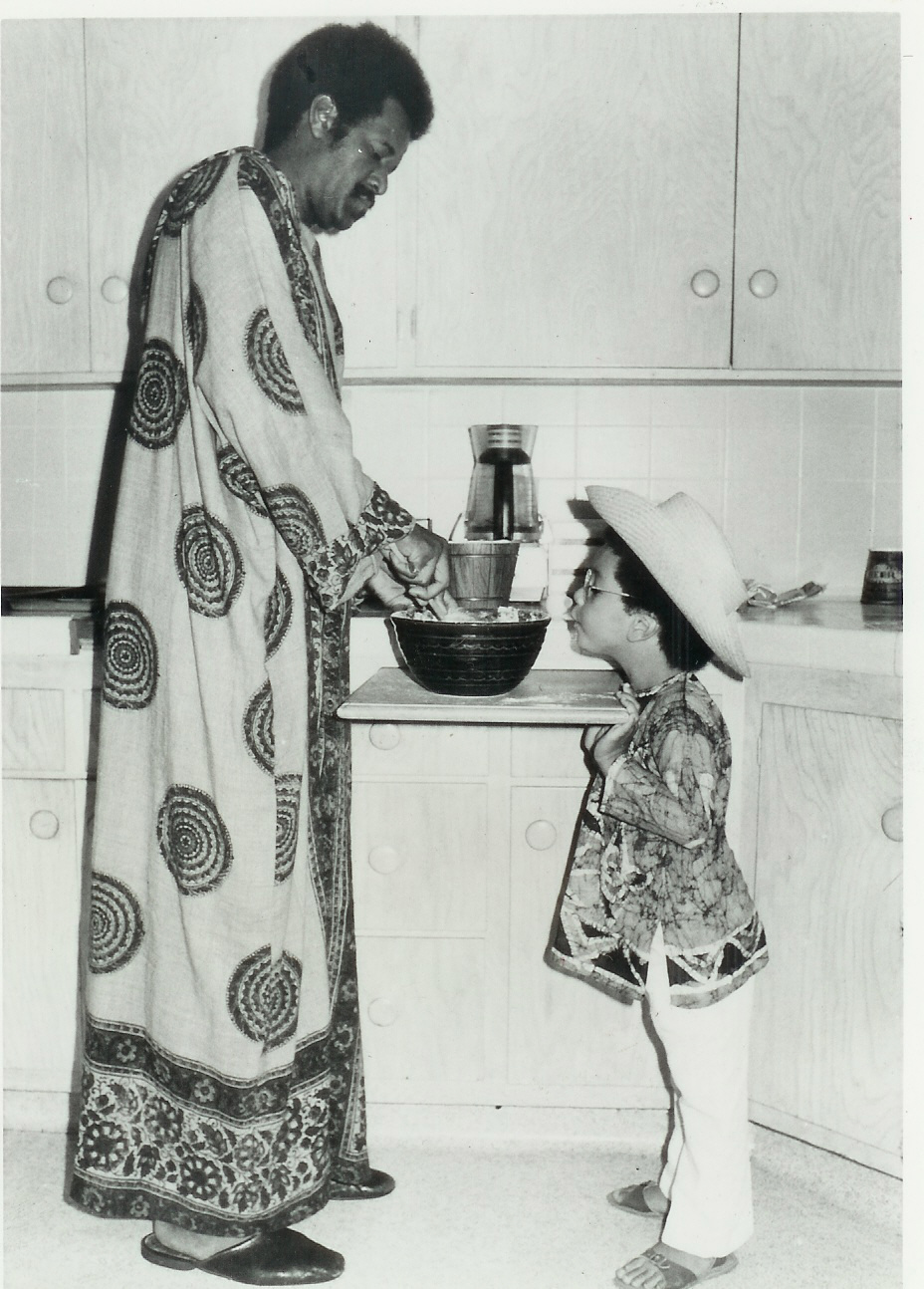

It also looked like the package of Nestle Semi-Semi Sweet Morsels that my father, Wally, had discovered at the rock 'n' roll Ralph's just one block west and used to make his first batch of Famous Amos cookies. If Toll House matriarch Ruth Wakeman were a reformed hooker, this would be her store. As it turned out, it became my father's.

In the '60s, my father, Wally Amos, had been a talent agent and a personal manager before taking a major career detour in 1975, when he opened a store selling chocolate chip cookies. In the middle of Hollywood, amid the hookers, drug dealers, and celebrities, my father served cookies and milk. The Famous Amos Chocolate Chip Cookie was an unexpected, unplanned pop culture phenomena. My father went from star-maker to star. Through the remainder of the '70s, Famous Amos was ubiquitous. He was on the cover of Time and People magazines, guest-starred on popular TV shows like The Jeffersons and Taxi, sat atop a float during the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, and hosted parties with such fellow pop culture icons as Muhammad Ali and Andy Warhol.

My father's very public life as Famous Amos was the opposite of that of his ex-wife, my mother Shirley, who was fighting a very private, solitary battle with mental illness. A former beauty queen and nightclub singer, she began slipping into psychosis before she and my father had their first kiss in a New York nightclub. By the time Famous Amos had become a household name, my mother had lost her career, her husband, her son, and her sanity. Her life was an endless loop of misdiagnoses, over-medication, under-medication, mental wards, denial, and guilt. The only constant witness was me -- her only son, whom she often confused with the husband she never could forget. Schizoaffective disorder is a big mental mash-up of a disease. It combines just about every disorder, from depression, delusions, and paranoia to mania, schizophrenia and hallucinations. My mother bounced between all of these regularly while raising me alone in our Hollywood home.

Somehow, I was able to navigate this life, and the contradictions of my childhood served me well as a young professional. I could adapt easily to a variety of people. My bullshit meter was finely tuned. Most importantly, I was able to compartmentalize, a survival mechanism that allowed me to manage a heavy workload while ignoring the repercussions of my childhood collateral damage. As a young married man and father, I was coming dangerously close to repeating my father's past and torpedoing my family as he had sunk his own. Like father, like son. For the time being, I would go to great lengths to avoid the similarities.

Compartmentalizing was the secret ingredient that enabled me to pretend my mother was just a quirky old lady whose calls I had long ignored. But a phone call on July 16, 2003, blew the dividers wide open. Off her medication for weeks, my mother committed suicide in her Raleigh, North Carolina, bedroom on a new mattress I had bought her just a few months before. A panicked lipstick scrawl on the mirror above her dresser read, "They killed Shawn. I love Wallace." A clue to a fabricated mystery plot starring her son and her ex-husband.

My father met me at the airport in Raleigh. We packed up her apartment just as I had done five months earlier in California. Only this time, I actually looked at the objects I was packing. Playbills of mom's nightclubs performances. Publicity photos of "Shirlee May," her stage name. A young, light-skinned black woman. She could almost "pass." The photos showed a woman who was sultry, controlled, and self-possessed. They were the photos of a woman I never knew. Shirlee May looked like the female lead in a Humphrey Bogart film. You could easily hear her saying the line, "You know how to whistle, don't you? Just put your lips together and blow." She probably did use that line. She probably used it on my father, who sat next to me staring at another publicity photo. Unlike me, he knew that woman. I wondered what he thought at that moment, whether he felt responsible for the way she had died, after all that he had inflicted upon her.

That night, my father and I sat in a Holiday Inn, our unplanned family reunion. My mom's ashes were on the night table in between our double beds, the three of us together in silence. We shared the space the same way we had our whole lives: separately. We were family in name only, related to one another by blood, but bonded more to our pain than each other.

We are born whole but fragile. And if we are lucky, no one drops us. Some of us, though, get broken. We are cracked across generations, and we spend the rest of our lives trying to put ourselves back together again. My childhood was created with a concoction of volatile ingredients: equal parts racial uncertainty, newly found fame, financial struggle, closely guarded demons, and a mythical, fantastically sleazy neighborhood. My childhood was placed at the intersection of the end of the civil rights era and the birth of the sexual revolution. My boyhood was the first success of the battles won in the '60s and the first failure of a generation of young parents like mine who knew how to succeed professionally while having no clue about how hold a family together. My parents' generation looked outward, not inward. That was the extent of their courage. It took all of their focus, determination, dignity, and grace to look outward, to be honest about the still smoldering divisions that sat just inches below a thinly veiled surface of tolerance around them. Yes, they were living in houses, driving cars, and holding jobs that their parents could have never dreamt of. But it was a tenuous truce, and they knew it.

My parents were not the only ones to hide their demons. I am not the only member of the Great Parentless Generation, this wandering tribe of latchkey kids constantly looking for -- and running away from -- home. So as the '60s were closing, my parents did what so many others have done for generations. They moved West. They came to Hollywood, which held the lure of escape and excellence that has attracted everyone from gold miners to movie producers. The cliche is real: Hollywood is make believe. And lots of people need to make believe.

Hollywood allowed my father to reinvent himself as a character named Famous Amos in an attempt to escape his history and family -- a bearded, amped-up Willy Wonka in blackface pushing cookies to a town full of '70s hedonists. Hollywood was a place used to keeping secrets. It kept the secrets of my mother, who had gone from promising New York entertainer to an invisible schizophrenic. And Hollywood was a surrogate parent where my own came up short, the babysitter who lets you get away with raiding the liquor cabinet and watching dirty movies. Hollywood opened its arms and gave me an education in the form of the show business hustlers I saw on movie studio lots, recording studios, and street corners where I played. The Hollywood of the 1970s was full of drug dealers, stoned musicians, and not-so-closeted gays. It was dubious, but not dangerous. Hollywood didn't ask any questions, and it let you peek in every forbidden corner.

The first chapter of one's life writes the ones that follow. Yet we are not the authors. Our first chapter is ghostwritten by the adults who surround us, by their actions and inactions. It wasn't until I was thirty-five years old and burying my mother that I glanced back at the demons that chased me. This is my first chapter: parents wrestling the American Dream, living a lie in La La Land, eating cookies and milk with the hookers on Sunset Strip.

Second installment: February 1

Shawn Amos is a singer-songwriter, producer and founder of digital media company Amos Content Group. His album, Harlem will be released February 15, 2011.