For decades, anti-rape activists have been fighting to raise awareness about backlogged rape kits, the forensic evidence gathered after a rape report is made. And yet, today, the Department of Justice estimates that there are more than 400,000 unprocessed rape kits in the United States.

One of these 400,000 belonged to Heather Marlowe. In May 2010, while at a party in San Francisco, Marlowe was drugged and raped. She went to the police, made a report and a rape kit was completed. Marlowe assumed that the police would investigate and contact her. After a year of waiting, she'd heard nothing back.

Marlowe followed up with the police repeatedly, working through a revolving door of people assigned to her case. She was told that her case file had been moved to Iron Mountain, a storage facility. "It could be anywhere from another six months to 10 years," until the kit was examined. When Marlowe asked why, an officer explained that her rape "was not a good enough rape," to pursue. "It will probably will never make it out of there because our lab is just too backed up processing more important crimes," explained an officer.

Do you know if your city is ignoring valuable evidence that could identify serial rapists?

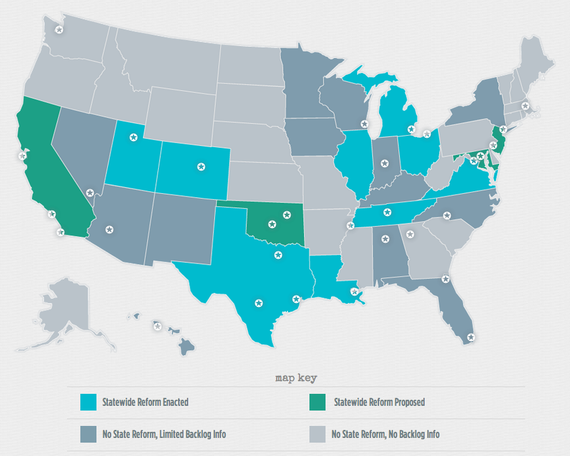

Seventeen states have introduced measures addressing backlogs. What about the others? Has your state or city take any action? Does your police department even know how many untested kits exist?

The San Francisco Police Department is responding to concerns. According to a spokesperson, a review of 10 years worth of sexual assault kits conducted in 2013 identified 753 to be processed. The department also created an ASAP kit, to be collected within 72 hours of a report and immediately transferred to the Crime Lab, where analysis has to happen within 14 days. Problems still exist, however. For example, SFPD has not responded to questions about the "several" thousands of kits that this of subset of 753 was drawn from. What happened to them and how were these selected? Give the size of the city, it could be anywhere between 5,000 and 10,000 given comparable examples. Additionally, the fast-track protocol was actually developed in 2010, but was only used, due to resource limitations, in unknown "stranger rape" suspect cases. Marlowe's was one of these cases, however. Her kit was finally processed, two years and five months after her rape, when a person with influence learned of her predicament and pressed the police department.

Marlowe, who never imagined herself as the rape kit poster child, is currently staging a one woman play called The Haze to raise awareness and pressure the SFPD to act. She started a petition asking the mayor of San Francisco to make the processing of all kits mandatory, regardless of whether the alleged offender is a stranger or known, to commit to improved training and to process all of the backlogged kits.

"Only processing 753 kits, while it is a start, has created a public safety crisis by allowing thousands of others to potentially keep raping other victims," she explains. She is working with the department, however, to share her experiences.

San Francisco is hardly alone. Faced with a similar circumstance in Houston, Valerie Neumann was told that it was "too expensive" to process her rape kit. The city, it turns out, had more than 16,000 unexamined kits. In one case reported by local media, an 87-year-old sexual assault victim's kit was untouched for nine years during which time a serial rapist, identified after it was processed, raped several other women. Last year, the Texas legislature passed a law mandating the processing of all kits. The city had so many it was able to negotiate, a "bulk rate."

Don't tell me, either that this isn't about cultural sexism, but about money or time or ignorance. This is a problem whose effects primarily disadvantage women, those most likely to experience rape and to report it and to advantage predatory rapists, most likely to be men. I know, I know.

The number of rapes reported annually, nationally, has been declining during the past 15 years. However, an analysis of federal data published earlier this year by Corey Rayburn Yung, at the University of Kansas School of Law, found that between 1995 and 2012, police departments across the country systematically undercounted and underreported sexual assaults. His conservative conclusion is that more than 1 million rapes are missing from our assessments.

One million missing rapes and 400,000 unprocessed rape kits, conservatively. It's outrageous and I can't figure out why people aren't up in arms. I mean, nail polish???? People are spending goo-gobs of money on rape avoidance products that, ultimately, just mean "rape someone else" instead of funneling funds into rape prevention solutions that demonstrably identify and stop predatory serial rapists. Capitalism is nothing if not consistent.

Here's a state-by-state map created by advocacy group End The Backlog, a program of the Joyful Heart Foundation.

Click here for interactive map. (Photo Credit: End the Backlog)

As you can see -- there are huge swaths of the country where data is missing. Dallas and Las Vegas each have more than 4,000. Cleveland, 3000. Chicago had more than 1,500. Human Rights Watch calculated that more than 80% of rape kits in Illinois were never examined.

"So many cities have refused to acknowledge or counted their back log. You count what you care about," explains Sarah Tofte, vice president, Policy & Advocacy at Joyful Heart Foundation. "Memphis didn't know until a year ago that they had 12,000 untested kits." The foundation's #EndTheBacklog campaign has been pivotal in putting pressure on local departments.

The good news, however, is that some cities are prioritizing this work and it's yielding good results. Memphis' processing of just 125 of their 12,000 kits has resulted in 30 indictments. In Detroit, which had more than 11,000 unprocessed kits untouched some as old as 25 years, 100 serial rapists were identified. In San Francisco, while it is problematic that no one would respond to my requests for an overall count, the city's new processes, today, have stopped the backlog of sexual assault kits.

"The rape kit backlog is important in and of itself," says Tofte. "But it's a tangible symbol of the failure of law enforcement to take rapes seriously and move them through the system. Just testing rape kits alone, however, is not enough. We have to change the way that agencies view sexual assault and sexual assault victims and their responsibility to them.

Unprocessed rape kits are one dimension of a much larger problem that continues to mask the high incidence of rape in the United States. Yung and others document how implicit bias and rape myths work in the treatment of rape by police officers. It is still true, and an impediment to people reporting sexual assault to the police, that victims often feel they are the ones being investigated.

Take Kendall Anderson, a student at Mills College in Oakland, California. Anderson went to the police to report being raped on campus last year, by a man who was not a student. She describes the room that she made her report in at the Oakland Police Department. It was an interrogation room. There were handcuffs on the chair that she was asked to use and, at one point, an officer who entered the room referred to her as a suspect. When Anderson asked if she could have a lawyer present, she was told "Why would you need a lawyer if you're not guilty of a crime." She was asked detailed questions about what she was wearing, if she was a virgin and, remarkably, why she was bleeding (she had an article of clothing to be used as evidence with her) if she didn't have her period. "After my exam revealed vaginal and throat abrasions," explains Anderson. "I was told by a detective that the sex I had was normal and I was confusing the idea of rape with rough sex. If I had known I had been subjected to this treatment I would have never reported my rape." The man whom she alleged raped her was never interviewed by The Oakland Police department, which declined to bring charges in her case. She is now actively involved in educating people about affirmative consent standards.

Anderson's experience with the police is a textbook case of the problems that people face when reporting sexual assault where studies show implicit bias and acceptance of rape myths are common. If women don't adhere to stereotypical ideals about "perfect victims" there is a high price to pay. This price is steeper yet again when the biases are racialized.

In general, I'm loathe to advocate for anything that suggests increased policing, but testing rape kits actually provides a good approach to some of the problems plaguing policing. The history of rape is one in which low status men -- based on race or sexuality -- bear the profiling and incarceration brunt of being the "typical" scary stranger rapist. Rape kits are a simple way to identify serial rapists who depend on these myths. DNA evidence also eliminates the targeting of innocent people historically accused of this crime. Prioritizing their processing is part of a much larger and necessary conversation.

In the spring, the White House announced that it would add $35 million, later increased to $41 million, to the 2015 budget. Today, the Senate adjourned without providing the funds tagged for rape kit processing and community-based sexual assault response initiatives.

In the meantime, as Yung put it when I spoke to him about his research, "the sheer magnitude of the missing data... is staggering." That data includes, critically, rape kits analysis.

__________________________________________________________

- Ask your police chief and your mayor's office what the status of rape kit processing is in your city? Ask specifically how many rape kits have expired and can no longer be of use. Not just a count in crime labs, but in property rooms and storage facilities. Not just the ones that are "important enough," but all of them. How many and whose deciding?

- Check this state-by-state list of laws regarding backlogged rape kits from the National Center for Victims of Crime.

- Support local activists and/or organizations that are raising funds to clear local backlogs.

- Make kit processing a political priority. Vote for people who understand why rape kit backlogs are important.

- Support existing funds and organizations, for example in Cleveland, Memphisand Detroit, where they are working hard on comprehensive reform, but operating with scant resources. Help individuals, like Marlowe, who are working hard with scant resources to force change

- Contact Senators and tell them to approve the budget allocation.

- Raise awareness, share the information on social media (using #endthebacklog) and news outlets and encourage others to do the same.

- Contact End The Backlog and let them know the status of what's going on in your city.