This Sunday marked the beginning of National Farmers Market Week, a hallmark first crowned by USDA in 2000, when the number of known farmers markets was 2,863. Since then, the tally has grown by more than 180 percent.

Grassroots commitments to invest in local agriculture have been bolstered by small but effective federal efforts to help grow farmers markets as engines of rural economic development. Many more Americans have affordable access to fresh produce (not to mention more social and civic engagement opportunities) as a result.

There's a lot to celebrate.

The colorful, sweet-smelling bustle of farmers markets is a welcome respite from ongoing news of corporate consolidation, scandals, and general inequality in America's dominant economic system. Farmers markets seem to emerge and thrive in response to our collective hunger for face-to-face relationships and transparent transactions that connect us with an evolving agricultural heritage.

But this year, behind the rainbowed mounds of melon and peppers, farmers are a little antsy. Amid celebrations taking place in communities across the country, they wonder how new federal food safety laws will impact their businesses.

In 2011, President Obama signed into law the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) -- the first overhaul to U.S. food safety laws since 1938. FSMA extended regulations all the way to the farm, but included considerations for local food systems and respected conservation and organic practices used, thankfully, by a growing number of farmers.

Unfortunately, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) -- the agency responsible for implementing FSMA -- appears to interpret the law differently. The way FDA defines "farm" and "facility" in the byzantine Produce and Preventative Controls rules leaves many growers confused about which rules apply to them. Additionally, the rules fail to properly address many proven-safe growing practices (like compost) and value-added activities (like freezing berries or drying herbs) utilized by farmers across the country. Depending on the sales thresholds FDA chooses, even low-risk activities like making jams, herbal infusions, pickles, and grain mixes from a farmer's own crops may be discouraged.

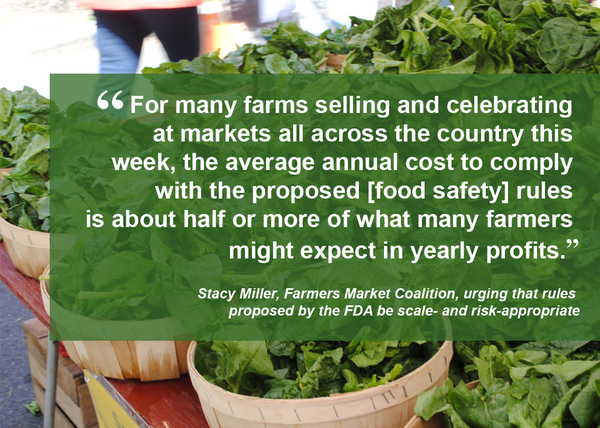

The agency's own economic analysis says "the rate of entry of very small and small [farm] businesses will decrease" as a result of the rules. Former U.S. Department of Agriculture Deputy Secretary Kathleen Merrigan said in a recent speech that the new food safety rules have the potential to "destroy some operations." For many diversified farms selling and celebrating at markets all across the country this week, the average annual cost to comply with the proposed rules is about half or more of what many farmers might, in a good year, expect in profits if certain ambiguities in the FSMA rule are not addressed.

Farms are changing, and that's a good thing. In nearly every farmers market in the U.S., there is at least one traditional livestock or commodity farm bold enough, despite historical government disincentives, to experiment by devoting a small amount of acreage to fresh produce. Even if their businesses are anchored by dairy or corn (which are not even covered by FSMA), and they sell a small amount of produce at farmers markets, they would likely be subject to the full extent of the Produce Rule requirements, as if they were growing thousands of acres of tomatoes for national distribution. With dairy and grain farms disappearing off the map every season, it's terrifying to think that one promising avenue for a family farm's viability -- diversification into produce -- may seem out of reach.

After years of working to build viable local food markets, growers like these are finally seeing the light of a positive balance sheet as people in their communities increasingly try to buy more locally grown and lightly-processed foods to support their local economies. Failure to make sure that new food safety regulations work for local farmers may put a halt to this market-based success story.

For example, at the height of market season, Portland Farmers Market draws 33,000 shoppers weekly to its eight markets who buy directly from 200 farms, nurseries, and local food entrepreneurs. The market is a small business incubator for Portland; more than 40 new small businesses have been launched by starting a booth at market. According to Operations Director, Jaret Foster, "about 15 percent of vendors are farmers whose value-added products like jams, sauces, dried fruits, or roasted nuts would qualify them as food facilities subject to the new regulations."

Proposed FSMA rules would significantly cut already-slim profits for the very farmers creating our communities' most unique, nutritious products in response to customer demand. Not to mention potentially deter potential entrepreneurs from starting new food ventures.

What impacts these producers impacts the growing number of people who rely on farmers markets to feed their families.

Food safety is not an issue that farmers take lightly. With strong relationships to local markets, their businesses are built on their reputations -- transparent growing and handling practices serve as the foundation of their work, and short supply chains are as accountable as it gets. Training on scale-appropriate best practices for growers diversifying and expanding, in this case, is more important than potentially punitive federal regulations that are difficult to enforce.

On the heels of a Cyclospora outbreak that has sickened nearly 400 people in 16 states since June, it's easy to see why improved traceability is needed in a consolidated system where contaminated products end up on millions of plates across the country. In at least two of these states, these illnesses have been linked to pre-packaged salad mix grown in Mexico and eaten at Red Lobster and Olive Garden (both owned by Florida-based Darden Restaurants). The very system that allows this to happen should be the focus of any federal investment in food safety.

Meanwhile, am I buying salad mix at my local farmers market this week? You bet.

The deadline for comments to FDA on both the Produce and Preventative Controls Rules is mid-November 2013.