As consumers we don't often think about who makes our clothing or whether a direct H&M supplier has subcontracted factory work to a small Cambodian factory that employs children younger than 15. It has. We think about how much a garment costs and whether it will look good on us. This isn't because we are heartless but instead because we haven't, as a society, developed a social conscience when it comes to consumerism (outside of food and perhaps children's toys, but that seems more concern for ourselves than those producing the food and toys).

How we, as a society, develop a social conscience is fascinating. It doesn't happen overnight and it can take decades to capture a collective audience. Think about littering. Discarding your empty soda bottle just inches away from a trashcan wasn't a big deal in the 40s. This began to changed in the 50s when nonprofit organizations, government agencies and a number of disposable packaging companies -- such as American Can Company, Owens-Illinois Glass Company, Coca-Cola, Dixie Cup Company and Richfield Oil Corporation -- got together and formed Keep America Beautiful (KAB). (Interesting side note: Author Heather Rogers states in Gone Tomorrow: The Hidden Life of Garbage that packaging companies founded KAB as a way to distract from the actual issue, production regulation.)

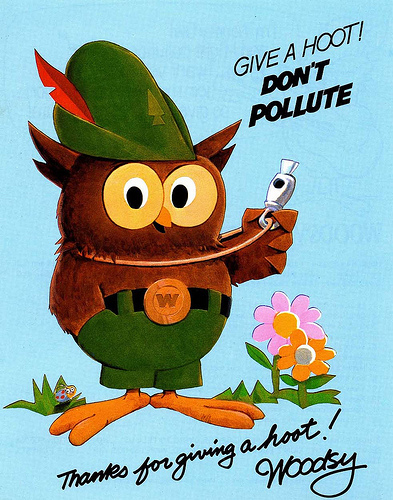

KAB along with the 1970s U.S.D.A. Forest Service campaign Give a Hoot! Don't Pollute aimed at school children didn't change perceptions or behaviors overnight, but they were strategic, targeted and, in the end, successful. That doesn't mean that everyone cares about the consequences of littering. I once returned a woman's discarded ketchup packets because it didn't cross my mind that she had intentionally littered them. She quite politely said thank you when I handed her the packets and then tossed them on the ground again. What it does mean is that because there is a cultural anti-littering mindset, we, as individuals, won't likely litter. In fact, it is perfectly acceptable to reprimand a stranger who has thrown the empty containers from his most recent meal out the car window.

It's similar to our cultural mindset on recycling. People take steps to recycle and we openly encourage friends, family and even strangers to do the same. "Do you recycle?" is a loaded question we may ask when helping a host clean up empty plastic and glass bottles after a social gathering. The only acceptable answer, of course, is yes. If the answer is no, we may graciously offer to rinse and cart home all of their recyclables, and perhaps give them a quick, and likely annoying, lesson on the benefits of recycling.

Clearly, some people still litter and don't recycle but the result of this collective mindset is that even people that don't really care about either participate because it's what society has deemed appropriate and right.

The environmental and human rights hazards of the fashion industry -- and frankly any production where brands outsource to un- or under-regulated nations -- is just starting to be on the media radar. It isn't commonly known that clothing production results in millions of tons of immediate waste (in C02 and H20 alone). Rapid production results in a lack of quality and most of these goods end up in the trash in a couple of years because they fall apart. (Textiles made up nearly six percent of the total U.S. municipal solid waste in 2012. That's 14.3 million tons of waste.) Effluent (waste) from unregulated dye houses turns rivers red, orange, purple and blue with toxic chemicals. This is where nearby residents pull their agricultural and drinking water, causing numerous health and developmental problems.

Lack of regulation in the fashion industry also results in debt bondage. It's a complicated issue but since most of us don't connect what we wear with human trafficking, here is a breakdown. Back in the 60s most our clothing was made in the United States. Then in the 70s companies began to outsource production and materials in countries with low-cost entry into industrialization. This allowed companies to expand their cost margins and increase production above and beyond what they could do at home. Not only did this squelch our local textile market, it also made monitoring incredibly difficult as it's hard to keep an eye on suppliers that are far away. That is if companies even attempt to do so and let's face it, many didn't and don't.

What makes monitoring even more complicated is that factories often subcontract their work and subcontractors do the same. So, in the end, companies often have no idea how their clothes were made and how workers were treated. The lack of regulation leaves gaps -- gaping holes really -- that allow unscrupulous people to step in and take advantage. It's an age-old adage. Create opportunity for people to take advantage and, guess what, they will. I would love to break it down for you by good and bad brands but even large sustainability-oriented companies face supply chain hurdles when they have convoluted supply chain. For example, Patagonia -- a socially conscious clothing brand -- discovered in 2011 evidence of debt bondage among seven of its suppliers. Patagonia wrote on their blog, The Cleanest Line:

We learned that it can take a worker as many as two years to repay a labor broker, and that most labor contracts last only three years before the worker has to return home and the process (and fees) begin again. It became clear to us that we needed to make significant changes--and to help alert others to both the problem and the need for change.

The issue was so pervasive that Patagonia responded by creating a policy in December 2014 that its Taiwanese suppliers stop the practice of charging recruitment fees.

Not only does outsourcing and subcontracting make an already complex supply chain more confusing and difficult than ever to monitor, it also cleverly creates fissures between brands and culpability. So you can see -- among companies that aren't sustainably focused -- why there isn't a huge incentive to change.

This is where we, as consumers, can actually make a difference. When I give talks about this issue, some audience members have said, "We can't really make a difference. Can we?" Yes, we can. As consumers, collectively, we have tremendous power in our pocketbooks. If we start to care about where our products come from, so too does the media. It's a powerful relationship. Brands abhor bad press because they know it can adversely affect their reputation and, in turn, how consumers purchase. Consumers, who are also constituents, then put pressure on legislators to create regulation that demands supply chain transparency and makes corporations accountable for their entire supply chains. Much like with recycling and littering, we can collectively buy-in to change.

If you believe corporations should be accountable for their entire supply chains, check out the Business Supply Chain Transparency on Trafficking and Slavery Act of 2015 (H.R.3226/S.1968), which was introduced to the House of Representatives on July 27, 2015 by Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) and Chris Smith (R-NJ). You can contact your congressperson and senators to support it.

Photo credit: U.S. Department of Agriculture

This post originally appeared on The Good Blog.