President Obama's visit to the West Bank took him into the center of the Palestinian tragedy where outrage over Israel's military occupation and civilian settlements has been punctuated by bursts of terrorist violence, quiet oppression, and demoralizing acquiescence. Yet the Holy Land hillsides that are carved by the towering walls that help keep suicide bombers from blowing up Tel Aviv cafes also testify to the Israeli tragedy of having to constantly balance the moral demands of justice with the urgent need for security.

It is into this despairing reality that yet another American president has traveled, mindful of the seemingly utter hopelessness of the Muslim-Jewish conflict in the Middle East, bringing the much-needed wishful thinking that, aside from weaponry, is the most cherished thing that the United States can gift to the people of Israel.

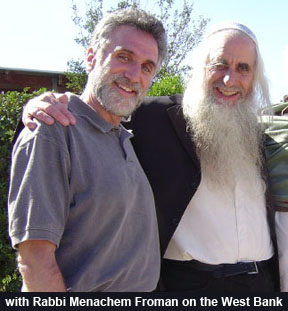

Such hope amid hopelessness was the obsession of the late Menachem Froman, who died just a few weeks ago. Froman was the chief rabbi of Tekoa, a settlement in the northern Judean hills of the West Bank that he helped established nearly thirty years ago. The paradox embodied by the orthodox settler rabbi who befriended Palestinian opponents like Yassir Arafat symbolized the struggles of two sides fighting for the same small patch of earth, a zero-sum battle that offers just the slightest of opportunities for American diplomacy whether it be conducted by Truman, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, Bush, Clinton, or Obama.

When visiting with Rabbi Froman in Tekoa, I saw the blooded sorrow of competing national claims up close, attendant with all its fears, slights, and desperate cries. Religious communities like Tekoa are among the most controversial Jewish settlements on the West Bank. To millions of Muslims everywhere and especially to the Palestinians who claim these lands as their own, such hilltop communities are symbols of an unfair religious domination by Jewish residents and an unjust military rule by Israeli soldiers. The people of Tekoa are loathed by the vast majority of the world's Muslims and are the targets of fierce Palestinian resentment.

In 2001, a 14-year-old boy and a 13-year-old boy who lived in Tekoa were discovered inside a nearby cave. Allegedly, Palestinian terrorists had crushed their skulls with rocks, killing them both. Rabbi Froman took me down to the cave where the bodies of the two murdered teens had been found. The lingering presence of these young innocent boys could still be felt, surrounding me with an aching sadness.

I asked Rabbi Froman how it felt to be the object of so much hatred. "Our suffering is a tunnel," the rabbi said. "The depths of our tragedies can be a path that leads us toward a greater compassion." Being the object of Muslim loathing fueled Froman's determination to express his love for the Muslim world.

Rabbi Froman even reached out to Sheikh Yassin, one of his most violent adversaries. As the founder of the Islamist militant group Hamas, Yassin had orchestrated numerous suicide bombings that targeted Jewish men, women, and children. Froman had hoped that Yassin would relate to him as one devout believer to another. "I spoke with Yassin about a truce on a religious basis," Froman recalled. "We Jews believe in our vision of the future, and you Muslims believe in your vision of the future," the rabbi told Yassin. "All believers know who runs the world. Why not leave something to Him?" Froman's message was rooted in religion: Let us have faith in His compassion. Let us put down our weapons and surrender peacefully to the fate that He intends.

The rabbi had appealed to the sheikh's shared belief that only God rules. And if we are to truly honor Him, Froman believed, then we must express the infinite compassion that He has given us. It's a sentiment that animates many of our most celebrated religious leaders who likewise cling to the promise of redemption despite the sinful cruelty of the present. "Abraham had two sons, Isaac and Ishmael," Billy Graham noted during the conversation that inspired my book, Billy Graham & Me. Reflecting upon the teachings of the Bible as our talk turned to the Mideast conflict, the Christian preacher testified to this optimistic vision of the faithful. "Ishmael is the father of the Arabs, Isaac is the father of the Jews," Rev. Graham said. "God promised that he is going to bless them both."

Yet many Arabs and Jews have surrendered to a more tragic prophecy. Hamas does not believe the Jews are worthy of blessings, and many Israelis accused Rabbi Froman of being too naïve. How could he sit down with the founder of Hamas, a man who sent suicide bombers to carry out terrorist attacks against Froman's own people? Yet even though the sheikh did not respond to the rabbi's plea for peace, Froman seemed playfully defiant in his optimism, exuding an open-hearted love similar to the kind we experience as children, before the cynicism of the adult world begins to close in on us.

While watching Obama travel through Israel and Palestine, I thought of Rabbi Froman. Knowing that America can broker but not impose a peace agreement, the president nevertheless carried the same spirit of insistent hope, taking it into places where hopelessness refuses to bend. "Ben-Gurion once said in Israel, in order to be a realist, you must believe in miracles," the president reminded, quoting the Jewish State's founding prime minister during his speech to college students in Jerusalem. "Sometimes the greatest miracle is recognizing that the world can change," he told his young audience. "That's a lesson that the world learned from the Jewish people." It's also a lesson that we can learn from Barack Hussein Obama, America's first black president.

Steve Posner teaches writing at the University of Southern California. Billy Graham & Me is his most recent book.