The Japanese spider crab is longer than most men are tall. In Suruga Bay, Japan, Emory Kristof created this image with the help of a camera mounted on a remotely-operated vehicle (ROV). (A second ROV's headlights can be seen in the background.) The crabs can grow as big as 12 feet, though this one is only about six feet across. "I was happy to let it wander away," Kristof says. Japanese members of his crew had other ideas. Like dinner. They asked if he could bring it up to the surface. Kristof calmly replied, "No, we don't want to do that. I don't eat my models."

(c) Emory Kristof/National Geographic Image Collection

"Going Straight Down"

National Geographic photographer Emory Kristof loves to do deep things no one else has done before. A few of his accomplishments:

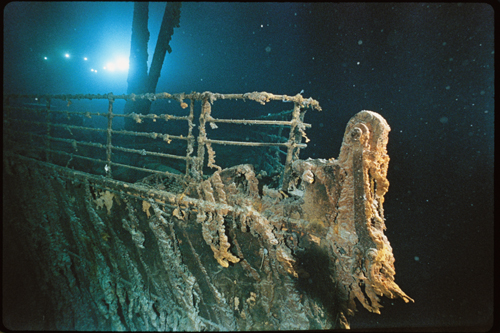

- He was part of the expedition that found the Titanic in 1985 -- more than two miles deep on the bottom of the Atlantic.

"If you want to do exploration," he told me, "there are two ways to go. One is straight up -- that takes a lot of money... The other is to go straight down. There is unfinished business on planet earth and some of it is in the ocean..."

Some Like It Hot

Watch the video below as Kristof explains the discovery of deepwater life forms near the amazingly hot volcanic rifts of the Galapagos.

That excerpt came from a lecture he gave at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles last month. (The whole lecture can be seen here.)

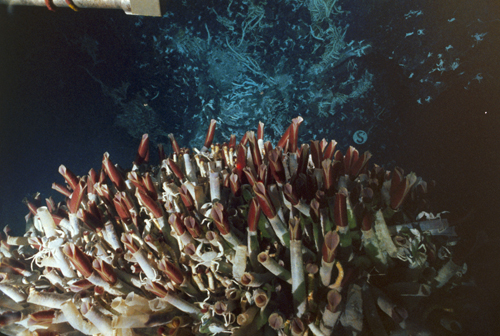

Kristof says it's like a "science fiction thing." Hot radioactive water spews from the Galapagos volcanic vents on the seabed 8500 feet below the surface of the ocean. On top of the vents sit red-headed tube worms (seen above). "It was believed up until this point that you couldn't have an animal living in water that was hotter than the boiling point because it would destroy a lot of the enzymes that make the animal work," Kristof told the audience at the Annenberg Space for Photography. "Yet we found these animals in 240 degree Fahrenheit water... This is probably the single greatest moment in my photographic career. I'm sitting down here. Looking at these really strange animals and noticing the temperature gauge." The vents, called black smokers, can release water at 750 degrees Fahrenheit. "You've got to be really careful that you don't get the windows [of the submersible] too close to that stuff because the windows will melt at 400 degrees." Fortunately, no windows melted and he went on to help make an IMAX film called Volcanoes of the Deep Sea (2003).

(c) Emory Kristof/National Geographic Image Collection

"Prince of the 20th Century"

Kristof's work at the National Geographic has taken him all around the world. In an interview before his lecture, he told me about some of his adventures.

You've had an amazing career.

"Gil Grosvenor [former president and board chairman of the National Geographic Society] just hung it up here a few weeks ago. [He retired in October, 2010.] We were both of us in times of service about the longest. I went there as an intern in 1963. And was the youngest staff photographer ever hired in '64."

You've had connection with them all the way through?

"The way I like to explain it that they have paid me every month of my life from my 20th year till I was 66 and a half. So I have been a staff photographer and a freelance photographer, too...

"In the 1960s, the Boeing 707 was introduced. For the first time in history, within two days you could go anywhere on the planet... With my job at the Geographic, I felt I was one of the true princes of the 20th century. I could go anywhere. Drop in. Look at it. Take pictures of it....

"I'm the Johnny Cash song, 'I Have Been Everywhere, I Have Been Everywhere...' I've been to all 50 states. I've been all over South America. I've been to the Middle East. I've been all over Africa. I've been all over Europe. I've been all over Russia and China. Finally, the biggest hole I had in my resume was the Antarctic. And so in 2002 and 2010, I put those dots on the map. I have a couple of projects I'd like to do underwater there. I've done a lot of work in the Arctic... What does it all mean? It turned out to be 51 stories in the Geographic. They trusted me to do these things and to be their field eyes."

Titanic Discovery

The bow railing of the Titanic. Kristof had to get into a submersible and go down more than 12,000 feet or 2.3 miles to get the shot. "I see a picture like this years before I make it," he said in his lecture. "Then all I have to do is get the pieces together, get the submarine, get the funding. I have had several projects that have taken 12 years to get together. And at my age (68) I can't afford to do too many more projects like that." Kristof is a pioneer in the use of submersibles and remotely operated vehicles. He created the preliminary designs of the electronic camera system for the Argo, the underwater vehicle that aided in the discovery of the Titanic. He also documented other shipwrecks, among them the Edmund Fitzgerald, the Hamilton & Scourge, the Breadalbane, the 16th Century Spanish Galleon San Diego and the interior of the USS Arizona. The story of the discovery of the Titanic became a big film -- literally -- on IMAX (in 1991, with Kristof shooting 3-D video). That was six years before James Cameron's Hollywood blockbuster was released.

(c) Emory Kristof/National Geographic Image Collection

People know you for your work with shipwrecks and deep sea creatures. Is there a part of your career that's less well known?

"The Geographic hired me because I was primarily a good people photographer and this was important to Bob Gilka [director of photography]. The other reason was that I was beginning to show some skill for doing things with remote cameras. I think of it as industrial type photography. And one of the first things they assigned me to do was a story on the US Air Force. This was back in 1964 when I first went on the staff. And I got to make pictures of rocket launches remotely and weapons delivery... I did a bunch of firsts - some of the first of Minuteman missiles launched from Vandenberg shot from a helicopter. ... I did pictures of F-105s delivering maximum rocket launch. Things that hadn't been done. And for a while with the Pentagon, with that story and the one I did on the Army, I had photos, big photos. [In the Pentagon itself] you'd go down a corridor and there'd be a Kristof picture of something blowing up or whatever. I must have set a record at the Pentagon for having big display pictures at the ends of corridors. It gave me a different look at the world....

I [also] did all these energy stories -- oil, wind, solar, land use, Tennessee Valley Authority... I got to see everything from chicken-shit methane to nuclear power. I got to see more energy projects that probably any photographer ever...

"Basically these stories are like a Master's degree by the time you get done with the research. Nuke power, I did 3,000 pages of reading on that one. The land use story was another 3,000 pages of reading... For a photographer, you think will all he's got to do is fill the photo list... I would do a lot of research. They would let me fly -- say if I wanted to fly to London for the weekend to talk to somebody to research the story -- they allowed me to do that. And a lot of my photographs came out of the research I was doing. So I like doing science stories and I liked doing research. "

I know from an online National Geographic interview that you used to practice diving as a kid, picking pennies off the pool bottom. Tell me how you got started with the very deep sea.

"I was assigned to go out in 1974 to do the first big scientific push in deep water. They had three submersibles working in the Atlantic on the mid-Atlantic ridge. They called the project FAMOUS -- French American Mid Ocean Underwater Survey. A couple things that I got out of that - one, the photography being done in the deep water by scientists was not very good... In fact, the main camera for working in the deep ocean -- the Edgerton -- had been built with a grant from the National Geographic Society back in 1951. Nobody had improved on it from '51 to '74. It had a 35 mm lens which was not very wide... I looked at that and said, 'Gee at the Geographic in shallow water we know how to make much better pictures...' Using wide angle lenses. Separating the lights more from the lens. Using more powerful lights. If we were to work with some of these science groups and just apply what we knew from shallow water we could improve the quality of the deep ocean pictures."

Monterey Canyon off California. Kristof said he was on the surface hundreds of feet away from the subject when he took this photo in 1988. He was using a device he has come to specialize in -- the remotely- operated vehicle or ROV. After some technical wizardry connecting a Nikon camera to a CCD camera and a 55 mm macro lens, he and his team were able to capture this image of a basket star without even dipping a toe in the water.

(c) Emory Kristof/National Geographic Image Collection

Has it been a pleasure to be working on the equipment side as well as the photography side?

"I feel we made a big contribution to the quality of the photography which made the science better..I've built a series of cameras I call ropecams. There basically baited cameras. I've done a lot here in California. Up there in Monterey. In the Marshall Islands, at Rongelap. In Kaikoura Canyon off New Zealand. Down at 5-6,000 feet you have a lot of animals... As far as I know, nobody has done work looking at those populations. If you have a lot of animals, what are they eating and why?... As we're fishing deeper, it starts to become important. Went down to Antarctica a few years ago to get a picture of a Patagonian toothfish. Now the Patagonian toothfish -- also known as the Chilean sea bass -- is caught on baited long lines.

"I have a nice picture taken at about 5,000 feet. I'm using baited cameras without hooks. All I want to do is feed 'em a good lunch and make a picture. But once you start fishing deep you've got by-catch. Then you find out, as they did with orange roughy, that these are very long-lived animals - the damn things [orange roughy ] go over 100 years old. But they have to be about 30 years old before they can breed ... You can wipe them up in no time at all... It seems whenever we've gone after a deep-sea fishery, we collapsed the numbers very very rapidly. So I felt it was important to look at. "

You defined it as your greatest thrill - seeing and documenting with your images creatures that nobody had known existed -- can you talk about that experience because to me it's the very essence of discovery?

"I was interested in the idea of exploration and doing something that nobody else had done. And let's say, trying to add something to the store of human knowledge... {And] here was an area, a big part of the planet, 70 percent of the planet, that was not being adequately photographed. This had to be worth something...

"There are some big damn animals down in deep water. You start bringing back pictures of [Pacific sleeper] sharks going on 30 feet. They make a great white shark look like a guppy. These are monsters. These are sea monsters. And then the discovery of the hot water vents, finding that up until 1977 we had missed over 50 percent of the bio-mass on planet earth... We're masters of the universe. We're masters of this planet. And we have missed over 50 percent of what's living on it because it's down in deep water.

"One thing about the ocean -- we are using the ocean very hard. There's a lot of us. We're using it for food, for dumping trash, you look at all the things we do in the ocean, and I'm not against fishing, but I'm not for wrecking all the furniture in the living room either. If we are going to use the oceans hard, we should know more about them."