In Chicago, the U.S. city that suffers the highest rates of gun violence and murder, a small team of unlikely adults employs a surprising technique to try to keep their kids alive. Part 1 in a 4-story series that first appeared on "Seeds of Hope" blog.

Auhor's note: All year, I write about tough topics: hunger, poverty, illness, inequity. Yet with this story, I struggled mightily. I can't understand why I spent part of my childhood in Chicago, but it was a completely different Chicago than the city I experienced through the eyes of the PBMR Center. I don't see why my sons grew up in safety, while the young men in the story below had to endure terror and violence beyond our worst nightmares. They've seen their sisters raped, their uncles' heads blown off, their moms shot up on crack. I'm shocked to witness that the depth of poverty in my former hometown rivals that of slums I've seen in Africa. I never knew that was possible in my beloved country. Yet the boys I met, both in jail and out, talked to me with such vulnerability they make me cry out loud. Their mentors at the program we are honored to support, who work 16-17-hour days, 7 days a week, rally with such faith it brings me to my knees.

There are many tales of gangbangers in "Gangland" or "ChiTown," but the video below is one of the most eloquent I've found. It sets to music all the heartbreak and hope with which these brave youth carry on, every day, on unforgiving streets.

Where is the hope here? For this team working with juvenile convicts and victims of America's worst drug and gun violence, it's in the youth themselves, whom they cite as "incredibly talented kids" with "surprisingly open hearts."

Source: The song "Brother" by Amir Sulaiman, from the album Like a Thief in the Night.

Chicago, IL: "I'm always shocked by how many of our kids say, 'Let me show you my bullet scars.' One boy in our program still has a bullet lodged in his abdomen. It's not really about being cool, like other teenagers with their tattoos: It's more like, this is who I am." -- Father Denny Kinderman, cofounder of PBMR Center for Restorative Justice, a program dedicated to keeping youth out of prison and alive.

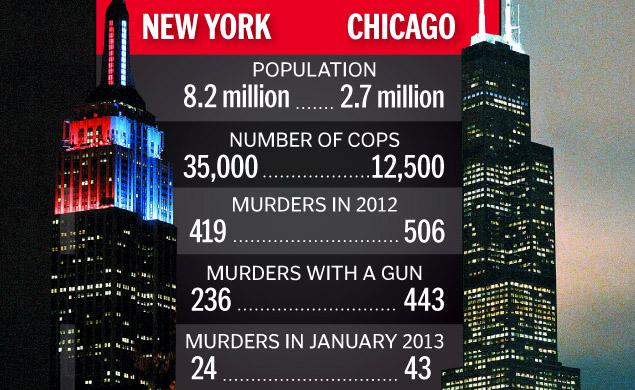

One-third the size of New York City, Chicago endured more murders last year: 506 deaths, 443 of them by guns. "That's the equivalent of a Newtown [CT] every four months," President Obama protested, decrying gun violence here. His wife agrees: First Lady Michelle Obama recently visited Chicago to help Mayor Rahm Emanuel raise funds for an anti-violence program for at-risk youth in the city. "Gun violence has become personal," she said, choking up over the murder of a 15-year-old girl. "Hadiya Pendleton was me and I was her," Mrs. Obama said of the slain teen who was shot a week after performing at the president's inauguration in January. "But I got to grow up and go to Princeton and Harvard Law School and have a career and a family and the most blessed life I could ever imagine." She's convinced that what kept her alive in Chicago was having adults who stood by her and being able to live in a safe community and attend a good school, reports Dorkys Ramos in BET.com.

Is There a Way Out of the Cycle of Violence?

New York City has proved that providing more police troops on the street drastically cuts both crime and incarceration. Many say, along with Harvard's Anthony Braga, who researches gang violence, that the key is to catch youth before they commit a crime. "Only five or six [youth, out of an average thirty members per gang] are what I would call truly dangerous; the rest of the kids are what we call situationally dangerous. If you can work with these kids, you can make a big impact."

We can't get kids out of prison until we address underlying social problems, insists Harvard sociologist Catherine Sirois. "Our priority should be, how do we keep children from growing up in communities where selling drugs is their best career option?"

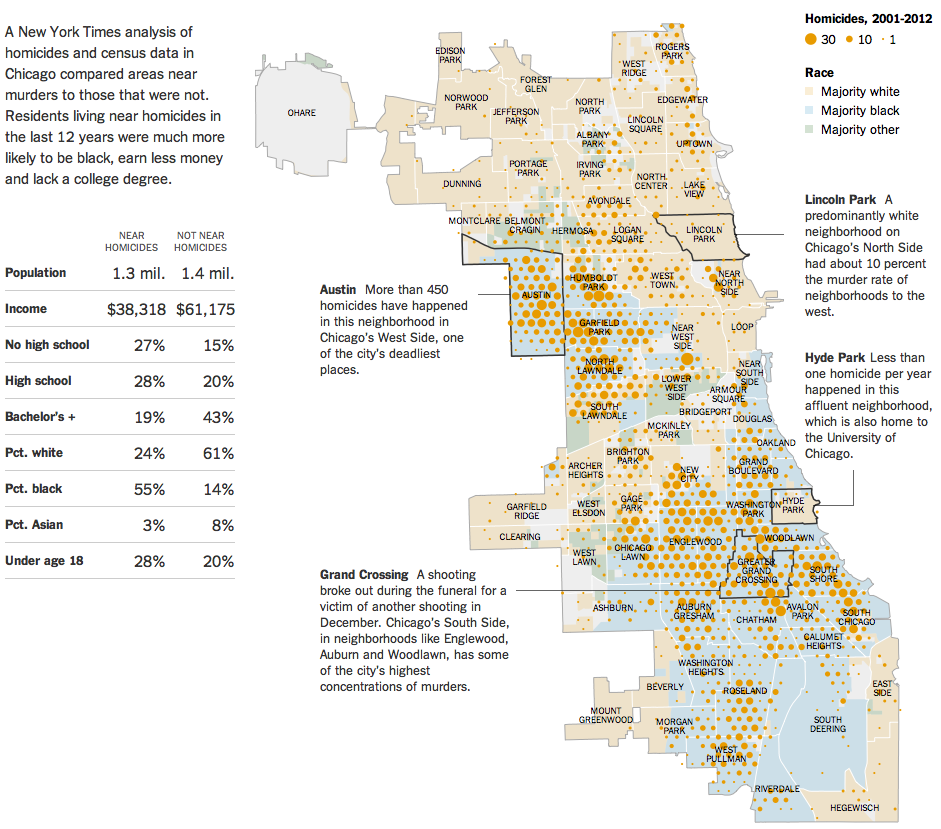

The New York Times mapped levels of gun violence per neighborhood to show the direct correlation between income, education, and violence. "Segregation is still a really big deal," reports Jamilah King for ColorLines in "Five Must-Know Facts about Chicago's Gun Violence." Note the high rates for "New City," a euphemistic relabeling of the "Back of the Yards" neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, where the PBMR Center is located.

Using Peace to Get to Peace

Here in the United States, where we have the world's highest incarceration rate: 2.2 million (more than half -56% -- of inmates are mentally ill, according to a study by Human Rights Watch), "two factors greatly increase the odds of going to prison sometime during one's lifetime," reports Harvard Magazine, in "The Prison Problem:" "being black or Hispanic, or being poor." Two other factors that increase odds of ending up in prison are lack of education and employment: all too familiar in urban Chicago. You might imagine the troops working for peace on the ground would be deeply invested in getting guns off their streets.

Yet "Gun law debates in Congress are one thing," says Cheryl Graves, founder of the Community Justice for Youth (CJYI), says, "but that won't really impact what happens on the street here." Cheryl worked for years as a trial attorney, and "I loved my work; loved the performance aspect of trial law. But it was an endless cycle of repetitive cases, with no reduction in crime. The system just doesn't change" through court and prison justice, she insists. Launching CJYI "to save lives and keep kids out of the court system" and in school, service programs, and jobs, Cheryl and her team have trained over 5,000 people in restorative justice. They've trained people from Kenya (ahead of their 2013 presidential elections) to Chicago. "We'll train people in circle-work wherever they go--the barber shop, beauticians, the old grandma who lets kids sit on her front steps after school," she explains.

Restorative justice partners (L to R): Father Dave Kelly, Cheryl Graves, and Sister Carolyn Hoying.

Cheryl works closely with the Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation (PBMR or "The Center") for at-risk and incarcerated youth. "There are some great organizations in Chicago, but there's no one like PBMR," she states flatly. "Their hospitality to these youth, the way they offer compassion yet also hold them responsible -- there's no one like them." They're both part of an informal network of 52 nonprofits, churches, and schools working together to offer a "hub" of holistic services to youth. Rather than the current use of restorative justice after a defendant has been found guilty, Cheryl envisions victim-perpetrator circles as "a precedent to or even a replacement for trial, if both parties are satisfied. They also could be used for conflict-resolution in schools."

PBMR Center cofounder Father Dave Kelly agrees that gun legislation won't help. "What we need is systems change," says the priest, who lives and works entrenched in the Back of the Yards neighborhood, headquarters of Chicago's high crime rates. "What we have are pockets in the city of deep, intergenerational poverty. People are wounded at a deep level and then live out of that woundedness," Dave reflects.

"Hurt people hurt people"

The root of restorative justice, according to Dave, is to heal wounds. He often says that "hurt people hurt people" -- and after working his entire career with gang members and convicts, he knows precisely the antidote to their pain: Restorative justice.

"People often think that restorative justice is soft and cuddly. It's the furthest thing from that --It's accountability and respect," he says. Key to the process of restorative justice is a communication tool known as a peacemaking circle, where family and community members affected by crime can talk openly about their experiences. Circles bring together members of opposing gangs, families who've been hurt by a member's crime, and often, both the victim and perpetrator of a crime. "Court is not a place for healing," says Dave. Yet "in our circle work, often I've known both the child who was killed and the child who did the killing."

"It's all about relationship," says the lanky priest, tipping his head forward in a diagonal nod. He and Center cofounder Father Denny Kinderman grew up in small Midwestern suburbs and worked together at a low-income urban parish in Cincinnati, Ohio before coming to Chicago and entrenching themselves in one of its most high-risk neighborhoods. Renting an apartment furnished with rats and roaches, right next door to the youth they wanted to reach, the two small-town white men hit the pavement, spending their first several months surveying "everyone from the local bishop to the ice cream vendor" about what locals needed.

"The number one concern was violence," Dave and Denny recall. They founded The Center along with Father Bill Nordenbrock and Father Joseph Nassal. Studying the work of Kay Pranis, they taught themselves and then their new neighbors how to conduct peacemaking circles. The PBMR Center, launched in 2002, sits amid grand old houses now crumbled into dirt lawns, peeled paint, and broken windows. Despite being named after their Catholic religious order (Precious Blood, a reference to the life-sacrifice of Jesus), The Center's priests and nuns are on a simple, first-name basis with the young men and women and their families. They will pray with members, but only upon request. The Center occupies the second floor of a formerly abandoned school; on the first floor is Second Chance Alternative High School, where kids can earn their high school diploma after prison or trauma. "I live here," quips Dave. "I'm not going anywhere."

For more information on the restorative justice work of The PBMR Center, check out this video by intern Hosu Lee for Northwestern University:

Precious Blood Center's Peacemaking Circle from Hosu Lee on Vimeo.

The Precious Blood Center hosts a peacemaking circle every Wednesday. Anyone from the neighborhood can come to resolve conflicts with others, receive counseling or simply talk about their lives.

Cover photo from MSNBC/AP; "Hub" staff photo by Suzanne Skees.

Parts 2-4 follow.

For more stories like this one, subscribe to follow me here on Huffington Post and on "Seeds of Hope."