While driving from Indianapolis to Baltimore last week, I saw a sign for the Antietam National Battlefield, a national park. I'd never visited Antietam, but was struck by the description of the battle in the excellent documentary Death and the Civil War. A "quick" detour turned into a 3-hour visit as the afternoon sun faded. I'm so glad I took the time.

On September 17, 1862, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, led by General Robert E. Lee, met the Union Army of the Potomac, led by General George B. McClellan, just outside the town of Sharpsburg, Maryland. The twelve-hour battle began at noon and was fought in the woods, fields, and farmyards around Antietam Creek. Nearly one-quarter of the 100,000 men engaged in the battle were killed or wounded, making the Battle of Antietam the bloodiest day in American history. The next day, Lee's army retreated back to Virginia, ending the first Confederate invasion of the North. President Lincoln seized upon the victory to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

The National Park Service owns more than 2,700 acres of the battlefield, including the sites of the key events, but many more acres remain in private hands. The 8.5 mile road that allows visitors to tour the vast site is shared by local residents; watching people engaging in their regular lives in the shadow of the battlefield is a poignant reminder that the Civil War was fought not on artificially constructed fields of battle, but in the midst of communities who were left to deal with thousands of dead and dying soldiers, their fields soaked with blood.

The reality of war and the widespread impact on the countryside was communicated after the Battle of Antietam by photos taken by Alexander Gardner and his assistant James Gibson two days after the battle. Gardner exhibited his photographs in Matthew Brady's New York City studio. The New York Times wrote that the photographs "bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along streets, he has done something very like it..." One of the sites photographed by Gardner after the battle was the Sunken Road, which was later renamed the "Bloody Lane."

Alexander Gardner's photograph of the Sunken Road on September 19, 1862. Burial crews, likely from the 130th Pennsylvania, stand on the ridge. The Sunken Road today:

On the day that I visited, there were less than a dozen cars in the 2,700 acre park. For most of the afternoon, I was alone as I explored each site. It was a beautiful Fall day, likely similar to the day 153 years ago when the landscape was darkened by the terror and confusion of war. It is hard to imagine so much death amidst so much peace and beauty, but it is even harder to forget.

Antietam National Battlefield includes the buildings of the farms that existed in 1862, including the Mumma farm and cemetery. Enclosed by a stone wall that predates the battle, it is a picturesque family cemetery.

I wandered among the stones in the cemetery, but was struck by one in particular. "Our Baby Boy," the simple stone reads; the fading monument to a beloved child who didn't live long enough to be named.

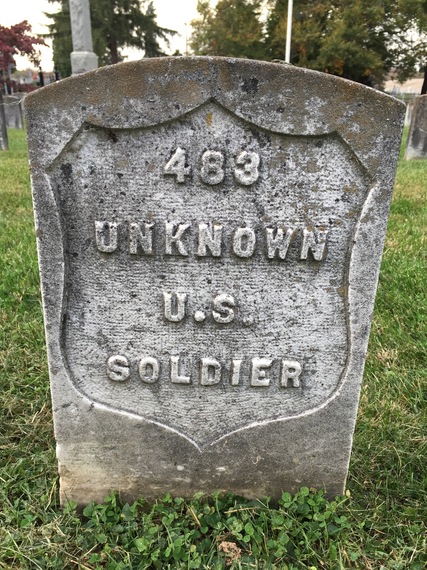

There are many tombstones to babies and children in 19th century cemeteries. Their frequency does not diminish the sadness that they inspire. But as I left the Mumma family cemetery to visit the Antietam National Cemetery, I was overwhelmed with realization that the thousands who died at Antietam were all someone's baby boy. Some of them, mostly Union troops, were eventually identified and buried with stones that identify them by name. But in an era before dog tags, many were buried without names.

Lee's Army retreated from Maryland following the Battle of Antietam, leaving their dead. The Union Army dispatched burial crews to deal with the thousands of corpses, but while Union soldiers generally received individual graves (even if their identity was unknown), the Confederate dead were typically buried in mass graves. Gardner's photo shows the remains of Confederate soldiers gathered for burial.

As the documentary Death and the Civil War reports:

Five days after the battle of Antietam hundreds of Confederate corpses still lay rotting on the field. Origen Bingham, of the 137th Pennsylvania, was assigned with his regiment to bury the neglected dead. It was, he said, "the most disagreeable duty that could have been assigned to us. Tongue cannot describe the horrible sight."

As the burial crews became weary, they began taking shortcuts. One burial crew threw the remains of 58 Confederate soldiers into a farmer's well.

The Antietam National Cemetery contains only the remains of Union soldiers. After the war, the federal government undertook the arduous and expensive task of locating all Union soldiers and repatriating them to individual graves, identified by name if possible. No such effort was made by the government for the Confederate dead. From Death and the Civil War:

In 1866, when Congress first proposed establishing a national cemetery system for the Union dead, only it provoked outrage in the south. Northerners were wrong, the editor of Richmond Examiner thundered, to think the Confederate any "less a hero because he failed." If the Confederate soldier, he wrote, "does not fall into the category of the 'Nation's Dead,' he is ours--and shame be to us if we do not care for his ashes."

It was mostly voluntary organizations, led by the mothers, widows, and sisters of the Confederate dead who raised the funds and coordinated the efforts to find their baby boys on northern battlefields and return them home. For example, the Hollywood Memorial Association of the Ladies of Richmond was founded in 1866.

Raising money through private donations, the women of the Hollywood Memorial Association set to work--organizing the repair, remounding and returfing of 11,000 graves dug at Hollywood during the war--and, with the help of farmers from battle sites on the outskirts of the city, arranged for the transfer of hundreds of bodies to new graves in Richmond.

The bitterness that this disparity inspired is still palpable when you visit Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

Of course the callous treatment of the Confederate dead was exploited after the war to help further the political narrative of The Lost Cause. Historian Vincent Brown:

It's worth going back and remembering the South didn't fight a war over the respectful treatment of the dead. They fought a war to create a Confederate States of America that would be a slave society in perpetuity. That was their war aim. Would that have gone away if the defeated South had been treated differently by the Union? I don't know. I know that's not why they went into the war, and that's not the cause that was lost.

Fair enough. But that does not change the fact that all of those who died at Antietam were Americans, whether they wanted to be or not, and that they were all someone's baby boy. Antietam is a haunting reminder of what happens when democracy fails. It is a difficult and necessary place to visit.