Have you ever heard of a tipperau? This is the first thing I ask my composition and creative writing students when I walk into a classroom on day one. They look at me, confused. I spell it on the board. No one has ever heard of a tipperau. It's an ancient Romanian architectural structure, and you're going to draw one right now. Now they really look at me. Like I'm crazy. I get a few whats and hows. (Especially when it's a composition class.) This is great. They're already outside of their comfort zones. Don't worry, I'm going to tell you what it looks like. But here's the thing: you have to draw it with your eyes closed. Usually here I get some laughter. But I mean it. I make them close their eyes, tell them I can see if they're cheating, and then add one more rule. No talking while drawing. We begin.

The tipperau is a large rectangular structure, wider than it is tall. On the right side of this rectangle is a tall tower. This tower has a triangular roof. At this point, they're really fighting the urge to open their eyes, and I usually hear a little laughter, some frustration. They want to ask questions, they want to get it right. On the left side of the rectangle is another tower, but this one is even taller. I don't want to spoil the secret recipe of the tipperau on the internet, but I'll tell you that I slowly describe a building similar to a cathedral (a bell in one of the towers, a large arched doorway), but with some quirky features like a circular window with bars and, finally, a moat--without a bridge.

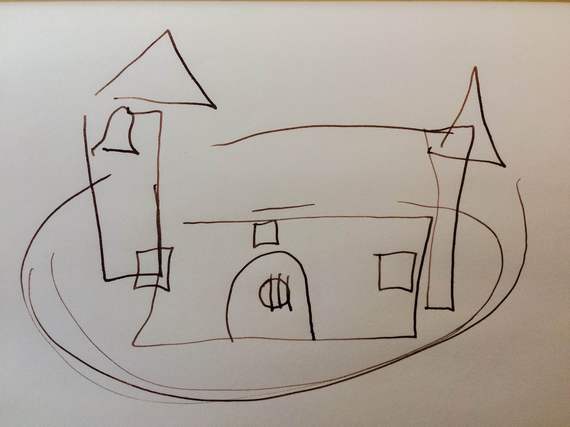

And now for the best part. They open their eyes to inspect their stunning asymmetrical, rudimentary drawings full of geometric shapes as scattered about as they are cohesively arranged. I make them hold their tipperaus up high and show them to their classmates. Everyone is laughing at this point. It's hard to be embarrassed about these beauties. The reasons are obvious, but I ask them why they're not embarrassed. The answers range, but say basically the same thing: we had no idea what to expect, and we can't be perfectionists with our eyes closed.

I tell them that drawing a tipperau with their eyes closed is what writing is like. Or, to be more precise, it's what any creative process is like. You begin with an idea you don't understand, and you move forward blindly, with an intuitive guidance that can't be explained. Or, to put it more simply, from a single word--even an unfamiliar one (especially an unfamiliar one)--we create a world. And through the creation of this world we begin to understand the idea. Even if we start with the same word and are given the same instructions, the worlds we create will be unique. Not one tipperau looks the same as another. This speaks to voice, which many young writers are afraid they don't have enough of. And the students are right, these worlds aren't perfect. These tipperaus, I tell them, are rough drafts. Rough drafts can easily look like the work of a preschooler, and these certainly do. If they were to revise--literally, I tell them, "to see again"--their tipperaus with their eyes open, the next draft would be more refined, their towers might actually be connected to the main rectangle. A final draft (well, I don't believe in the word final when it comes to poetry--I prefer to say "leave-alone-able") is a destination reached only through a process like this one. Process builds skill, and, to quote poet Elizabeth Bishop, "Writing poetry is an unnatural act. It takes great skill to make it seem natural."

Do you know why you've never heard of a tipperau? I ask the students. Most times they know, sometimes they don't. Here's where I tell them I made it up. Our brains seek to make sense of the unknown. Minutes ago they had no idea what I was talking about, but now the tipperau exists as a visible and believable structure in their minds.

My father and Raymond Carver inspired this exercise. My father is the most imaginative person I've ever met. He can prank anyone into believing the most absurd story. His secret, he once told me, is to begin with the believable, then to gradually add components of the unbelievable. This is how he taught shapes to me. We'd sit side by side, each with a piece of paper and a crayon. Square, he'd say, and he'd draw one. I'd copy. Rectangle. Triangle. Circle. Slibeedoo. The slibeedoo, a structure that included all of the shapes interconnected, was something I believed to be real until the middle of kindergarten. This simple art lesson taught me how imagination shapes new realities for the mind. Turns out it was the best lesson for my writing. Now, on to Carver. After I read his short story "Cathedral" for the first time, I wanted to experience what the narrator felt as he sat on the carpet drawing a cathedral with a ballpoint pen on a shopping bag, eyes closed, the blind man's hand around his own. I drew a cathedral with my eyes closed. It looked shitty. I was a beginner again. And, aren't we always beginners again in everything we do? This exercise made me remember this. It felt fantastic.

So, is creative writing something that can be taught? I'm not so sure it can. But I do believe teachers can create a space in which students see beyond their conscious and subconscious limits and challenge themselves to realize that they do know how to create a unique world, whether it be a poem, story, or essay. And the worlds of the genres-- they're not so different when you picture them as, say, an imaginary architectural structure made from a nonsensical word that you're attempting to draw with your eyes closed. My advice about teaching creative writing could be summed up by the blind man in "Cathedral," who created a space for the narrator to revise the way he saw the world he created on a sheet of paper, and also the world beyond that page. Close your eyes now. Keep them that way. Don't stop now. Draw.

This essay originally appeared in Best American Poetry.