Financial markets live in terror of the day the Federal Reserve raises interest rates. However, we should fear exactly the opposite: a persistent nightmare of low interest rates. Chronically low interest rates signal trouble, and they inflict financial pain. Ominously, a recent economic poll (interpreted correctly) suggests that interest rates are going to fall, not rise. But we'll get to that later.

Conventional wisdom: Low rates stimulate the economy

Economics 101 argues that low rates cause economic growth because consumers take advantage of them to finance home purchases; businesses, to build factories and hire workers. Consequently, the economy should grow faster: low rates stimulate the economy.

The recent U.S. stock market surge has accompanied signals that the Federal Reserve will keep interest rates low for a long time. After Federal reserve chair Janet Yellen spoke at the Jackson Hole conference last Friday, a Business Week headline blared: "Yellen: Rates will stay low even after QE ends this fall."

The conventional wisdom: low interest rates are good for both economic growth and the stock market.

Three flaws in the conventional wisdom

Unfortunately for the conventional, the "wisdom" of low-rates-stimulate-growth omits three features.

First, the primary effect of low interest rates on wealth is exactly nothing. For every borrower who pays $1 less in interest, there is a saver who receives $1 less in interest income. Any economic growth is second-order; lower rates transfer wealth from savers to borrowers.

Second, the conventional wisdom misses the time element associated with low rates. We have already received most of the benefits that we are going to receive from low rates, but the costs of low rates will extend for decades.

A joke illustrates the point. An elephant and a mouse meet in the jungle. They fall in love and have a passionate night of romance. The mouse wakes nestled in the elephant's trunk, only to find its lover is dead. As the mouse begins the process of digging a huge grave, it says, "Such is life, a few moments of passion, followed by a lifetime of work."

Similarly, the benefits of low interest rates come immediately, while the pain lasts for decades.

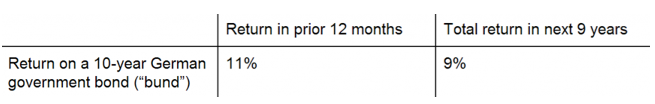

Consider the recent experience of an investor in German 10-year bonds. Over the last year, the interest rate on 10-year German bonds has fallen from roughly 2 percent to under 1 percent. An owner of German bonds received a tremendous return of over 11 percent in the past year because the bonds rose in value as the interest rate dropped -- 2-percent bonds are worth more in a 1-percent world. But the same investor now faces a total return of under 9 percent in the next nine years: a mere 1 percent a year. More than half the return on this German bond came in the first year when the interest rate fell. Investors who own these German bonds now will earn very low future returns. And if interest rates rise, today's bonds will be worth less.

Similarly, most benefits of low U.S. rates have already occurred. People who owned U.S. Treasuries and other bonds in 2011, 2012, and so far in 2014, reaped huge benefits as interest rates fell and bond prices rose. While falling interest rates produce a great one-time benefit, the future for bond investors is bleak.

The reality of investing in a low-interest-rate world has not sunk in for most investors. Here is an exercise that you can perform to understand your future. Take your financial assets and multiply by 2.4 percent, the current yield on a U.S. 10-year Treasury bond. If you have $100,000 saved, you have $200 per month to live on before taxes and inflation. Can you live off your savings?

Most people cannot survive earning 2.4 percent. Only the top 1 percent can live off their savings. Many people are poorer than we realize because we overestimate what we can earn on our savings. When we comprehend how poor the Federal Reserve has made us, we will start consuming less, which will be tough on us, and bad for an economy dependent on consumer spending.

Americans everywhere are struggling with the realities of low returns on our savings. On a recent visit to Disneyland, an elderly employee, who looked about 75 years old, searched our family backpack at the entrance to "the happiest place on earth." He asked how I was doing, and I said, "Great," then asked how he was doing. Knowing that he could be fired for what he was about to say, the senior citizen employee whispered with disgust, "NG -- not good. Working hard for very little."

Lower interest rates are not only a problem for bondholders; they also hurt Americans' pensions. Most corporate and public pension plans are "underfunded" in that they do not have enough money to cover future payouts to retirees. Amazingly, these plans are underfunded under the assumption that they can earn more than 7 percent a year on the money they have invested.

How can a pension fund believe it will earn 7 percent in a world where Treasury bonds pay only 2.4 percent? The answer is by taking huge risks.

Pensions increase their risk by buying emerging market debt, risky stocks, and investing in riskier areas via hedge funds. For example, San Diego's pension plan aims for high returns by using derivatives and leverage. Watch this PBS NewsHour Making Sen$e video to see the problem even in conservatively managed Rhode Island.

The fact is, pension funds are unlikely to earn 7 percent. They might not earn anything at all if the stock market declines. And in the event that pension plans return less than their assumed 7 percent, everyone pays. The public pension plans will ask taxpayers for support. Even private plan failures will impose costs on others as they raise product prices and lower dividends. Some private plans will fail and seek government assistance from the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation.

Conventional wisdom that low interest rates are good overlooks the facts. First, low interest rates primarily take from savers and give to borrowers with no net gain. Second, the benefits of low rates have already occurred, while the pain will persist for decades. And third, low rates contribute to the underfunding of pension plans, which will impose costs on both retirees and non-retirees.

Just look across the Pacific

Japan is the poster child for the failure of low interest rate policy. In the 1980s, Japan led the world in many economic areas; now it is near the top in debt and stagnation.

Japanese interest rates are far lower than U.S. rates, and Japanese rates have been low for much longer. A hundred thousand dollars invested in 10-year Japanese government bonds yields just $40 per month in income before inflation and taxes. Consider that even $1,000,000 invested at the Japanese rate produces just $400 a month in pre-tax income. It is no wonder that Japan is struggling. Low rates have not helped the Japanese, and they won't help Americans either.

And the bad news is that U.S. interest rates are likely headed lower. This spring, 100 percent of surveyed economists predicted rising rates. And if 100 percent of economists believe anything, they are almost surely wrong.

The unanimity that U.S. interest rates are going higher is as good a sign as possible that we should prepare ourselves for a depressed and depressing world of persistent low interest rates.

Instead of fearing a Federal Reserve interest rate rise, we should be on the lookout for an interest rate collapse. You can monitor the situation by watching the 10-year Treasury interest rate. (See the bottom right of the Google finance page.)

The worst news for most people, and particularly for savers, would be an announcement this fall or early next year that the Federal Reserve will not raise interest rates in 2015. In this scenario, the 10-year Treasury rate could drop below 2 percent and could even approach 1 percent. Wall Street might cheer a delayed Fed rate increase, but for Main Street, and certainly for savers, such a delay would be nothing but bad news.

Terry Burnham is a regular contributor to Making Sen$e with Paul Solman at the PBS NewsHour Online, where this post originally appeared.

Catch up on past articles by Terry: