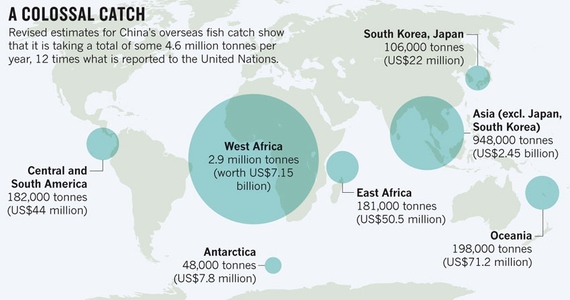

Lawlessness at sea is a hot topic this summer, with the New York Times running an investigative series on the issue and the nascent Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI) beginning to pick up steam. Two experts from Greenpeace connected the dots for me and explained why we should care. Dakar-based Marie Suzanne Traore (MT) is the pressure group's Oceans Campaigner for West Africa, covering an area stretching from Cameroon to Mauritania. Brussels-based Justine Maillot (JM) is its Oceans Policy Adviser.

We spoke about how international fishing in African coastal waters is governed, the differences between European, Chinese and Russian contractual approaches, the impact on ecosystems and local livelihoods, transparency and access to information in the sector, and the many loopholes and corruption risks in the sector. Note that I did not fact check any of the information or claims made by them in this interview.

Can you briefly explain how foreign fishing in West African waters is regulated?

JM: There are two forms of fisheries agreements. The first kind is state-to-state. This is the option preferentially pursued by the European Union, which negotiates fisheries partnership agreements with individual West African countries. These agreements consist of a broad framework agreement plus specific protocols that specify the exact numbers of boats and catch quotas allowed as well as the financial compensation provided by the EU. Individual EU member states cannot negotiate bilateral agreements with foreign countries as fisheries is an exclusive EU competence . In addition, when the EU has such an agreement in place, vessels flagged in an EU member state cannot directly negotiate with West African governments to seek additional permits. (However, EU operators using a vessel not flagged in the EU probably could get extra permits.)

JM: The second kind of agreement is private-to-state. These agreements are only struck when no state-to-state agreement is in place, between a foreign fishing company and a West African country. In these cases, commercial operators negotiate directly with host country officials. The home government of the fishing company typically may have to endorse the deal, but this is still the exception rather than the norm, and in any case the government is not involved in the negotiations themselves. In the case of Spain, the private agreement has to be officially validated and payments for licenses are made through the Spanish government directly into the national treasury of the host country.

Fishing in the high seas, i.e. beyond the areas of national jurisdiction, is yet another matter.

Do fisheries agreements with Russia and China take the same forms?

JM: Russia has state-to-state fishing agreements with several West African countries. Regarding China, my understanding is that they only have private agreements with West African countries. However, note that CNFC, possibly the biggest Chinese fishing company, is state owned.

MT: Chinese payments to national governments are not transparent at all. This should be public information, this is a resource that belongs to the country of Senegal, as a Senegalese citizen I should be able to see this data. As far as I know, the only state actor that publishes what it pays is the European Union, though I'm not sure about countries like Chile or Iceland.

How sustainable are the provisions set out in European Union fishing agreements with West African countries?

MT: The EU has changed and somewhat improved its policies over the past decade. However, from an environmental perspective, these agreements due not ensure sustainability. For example, the agreement with Senegal allows 38 European boats to operate in Senegalese waters; two of these are bottom trawlers catching Black Hake, a species that is already overexploited. Another 28 of those boats target tuna. These so-called 'seiners' fish in an unsustainable manner, overfishing tuna stocks while also catching and then throwing overboard many other fish.

In Mauritania, the new agreement [from July 2015] allows EU vessels to catch small pelagic stocks. These are a strategic species as they directly affect the food security of local small fishermen and coastal communities. A large share of protein consumed in Mauritania and other West African countries comes from these small pelagics, as they are the most affordable source of protein for many families. Allowing EU vessels to fish for these species puts foreign commercial vessels in direct competition with Mauritanian artisanal fishermen. It could also undermine the positive decision taken by the president of [neighbouring] Senegal, Macky Sall. He exclusively reserved the small pelagics in Senegalese waters for local fishing vessels to preserve local comunities' livelihoods. This was a first step toward sustainable fishery policies in the region, but the North Atlantic coastal countries share the same stocks, so EU fishing off Mauritania will necessarily impact Senegalese stocks.

Overall, most stocks off the coast of West Africa are already overfished.

Who is responsible for unsustainable overfishing, the EU or the governments of coastal states?

MT: Both bear some responsibility. It is not normal that our [African] governments continue to give licenses to boats that fish unsustainably and destructively. So Greenpeace advocates for sustainable legislation in African countries, for example in the context of the Senegalese fisheries code. We give legal input, lobby with MPs, and link up with other NGOs.

The EU must be vigilant about the fish that enters its harbours and determine whether it was illegally fished or not. If comes from illegal fishing, that is a crime and the fish was stolen, it's theft.

MT: European interests and local [African] citizens' interests are not necessarily aligned. We can and sometimes do ask the EU to put pressure on our governments, but they often have no vested interest in pursuing this. With regard to Senegal, we were once told that the EU "did not want to interfere in internal matters".

On the positive side, when the EU comes and negotiates a fisheries accord, it earmarks part of the money as support for the local fishing sector, though it still needs to make sure that these supporting activities and/or projects are conducted in a participatory and transparent manner. Also, in Mauritania, it supports the government's ability to independently monitor fishing, which is great. Other countries such as China and Russia do not do this. Also, the EU does pay at least some attention to sustainability in its agreements, which other foreign actors do not, despite formal non-discrimination clauses.

How transparent is the fisheries sector in the region?

MT: The main lack of transparency is not on the European side, but on the side of African countries. For example, in Guinea-Bissau, a former senior government official was recently charged with selling fishing licenses under the table.

Having said that, the [EU] negotiations themselves take place behind closed doors, they need to be far more transparent and participative. In Senegal, more than 5,000 artisanal fishermen have signed a petition against their government's agreement with the EU because they were not involved in the negotiations. Senegalese industrial fishermen were not represented at the table either.

What data on fisheries agreements is publicly available?

JM: Commercial operators from EU states must apply for individual licenses through their national governments, and the national-level decisions are then passed on to the EU commission for final approval. We do not know which individual vessels are fishing under the EU partnership agreements, which of them have secured licenses. This information is not made publically available, I wouldn't be able to find it.

However, the EU Fishing Authoritisation Regulation that governs this licensing process will hopefully be revised later this year. The European Commission has realized there is a lack of transparency, and it is something that I know they want to address during the revision. A proposal is due to be finalized in autumn, then it will be discussed in the European Parliament and Council of Ministers.

Have you tried getting hold of data on private agreements via freedom of information requests?

JM: No, we have not tried to get information through this route in the past. The process is very, very intransparent. The European Commission and certain member states themselves may not be completely aware of who is doing what.

We have no information on any private agreements between West African countries and private commercial operators. Those are completely opaque, except maybe those by Spanish and French operators.

Are there loopholes that European fishing operators can use to exceed the limits set in bilateral agreements?

JM: The biggest loopholes are flag-hopping, joint ventures, and chartering agreements.

With flag-hopping, you fish six months under the EU agreement and use up your boat's quota, then you change flag [and flag as a non-EU foreign country] and negotiate a private license with the Mauritanian government. That has happened a lot in the past, not only with EU vessels. Ships change flag every six months and just keep fishing. The most recent Common Fisheries Policy has improved in this regard. The new rule is that you need to have been flagged to an EU country for the last 24 months to get a license. There is an exception though, if the owner proves that the boat was operating under rules equivalent to EU standards. We want to see this rule tightened up even further in the upcoming new Fishing Authoritisation Regulation.

MT: Arrangements such as joint ventures and chartering agreements are the other big loophole. A boat owner from Spain or China can charter his boat with a Mauritanian or Senegalese company or operate through a joint venture and fish as a domestic boat, under domestic rules. In the case of joint ventures, foreign distant water fleet operators set up a joint venture with a local company or representative and reflag to the coastal state, and are therefore considered as local fleet. The Chinese do this a lot, they set up joint ventures with a Senegalese company and fly the Senegalese flag. In chartering agreements, foreign distant water fleet operators charter a vessel flagged to the coastal state for its fishing operations. There is no clear and set definition of those two mechanisms in international law.

JM: The fact that there are no clear rules, requirements, or transparency on private agreements is also a big loophole in itself.

What are the corruption risks associated with EU agreements?

JM: EU fisheries agreements involve payment of a headline sum for the right to fish in national waters, and then a second sum for developing the local fisheries sector within the African partner country. The headline sum goes straight into the national budget as unrestricted funding. To what extent you can monitor subsequent expenditure depends on the transparency of national systems.

As to the development funds, they are explicitly earmarked for this purpose and are paid into a separate account that is managed by the counterpart national government. So, these funds are not channelled through EU development agencies or EU-selected subcontractors. I am unclear whether the EU has to give its formal green light to any specific projects financed from this money. There is usually a reporting clause in the fishing agreement but the question remains open whether this money is really going to its designated purpose or not.

MT: These [development] activities are implemented by the EU, who control the use of the funds, they do not give that money to counterpart governments. I do not know how exactly that money is spent, but in the case of Senegal, local fishermen and civil society were not included in the committee that discussed how these supporting funds would be spent. If you have only the two governments negotiating, I have doubts about the effective use of this money, there is no guarantee that all of it is being well spend. It would be better to also have local fishing representatives at the table. We need transparency and good governance in the sector.

What about the requirements to land some of the catch in Mauritanian ports?

JM: These requirements are intended to promote the development of a local fishing industry. Big EU fishing operators sometimes claim in the media that these contribute to food security, but their claim is doubtful. In the short term, fish caught on an industrial scale may be cheaper for Mauritanians, but it could also put artisanal fishermen out of business. And in the long term, of course, fishing by the EU and other nations at the current levels could undermine food security, as it's unsustainable for certain stocks and leading to their depletion , destroying what should be a long-term resource.

Who is responsible for ensuring compliance with the quotas set out in EU agreements?

JM: The individual [EU member] flag states are responsible for monitoring. Each company will have an individual limit set out in its own license, and under international law, the primary responsibility to ensure that vessels stick to these numbers rests with the flag state. On the receiving end, coastal states also keep an eye open, but the control capacities of states in West Africa are very limited. Having said that, we have recently seen more action from [the governments of] Guinea and Senegal because they have realized that it is in their interest to control this.

What are your chief ecological concerns related to fisheries in West Africa?

JM: Pelagic stocks are Greenpeace's main worry. Most of those stocks are overfished in the region. Also, most of these species are migratory, so they need to be jointly managed by Morocco, Mauritania and Senegal. Under EU rules, European vessels can only fish the so-called "surplus", i.e fish that is not caught by the local fleet, or other distant water fleets, and is still within the levels required to ensure sustainability, but it is very hard to assess the surplus for migratory pelagic stocks. There is huge concern over the overfishing of these species, not least because they are essential to food security in West Africa.

JM: Fortunately, the new [July 2015] draft protocol [with Mauritania] does not allow EU vessels to take out any octopuses, maintaining the prohibition from the previous protocol. The agreement reserves them for artisanal fishermen in Mauritania. However, the Mauritanian government seems to be allowing Chinese vessels to fish for octopus - we don't know, it's not clear.

So there are different rules for EU vessels and Chinese fishing boats?

JM: Yes. In theory, there shouldn't be because there's a so-called "non-discrimination clause" in the EU agreements, committing [African] host countries to apply the same rules to all their international counterparts. However, for example, it seems that EU boats cannot fish for octopus in Mauritania but Chinese boats can. The same dynamics equally apply to minimum distances from the shore, the rules differ. Of course, this can be used to put domestic pressure on EU politicians to secure equally unsustainable conditions at the negotiating table. The last EU protocol for Mauritania is generally good on paper but those standards should similarly apply to non-EU fleets.

What is your take on the embryonic Fisheries International Transparency Initiative (FiTI)?

MT: We welcome it. Just as there is the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in the mining sector, we need standards in fisheries across West Africa as well. FiTI have already contacted us and encouraged Greenpeace to become member of its advisory committee. It is a good occasion for us to give input into future standards for the fishing industry. They will be voluntary standards but we can use them to put pressure on governments, both African and external, to meet these standards.

FiTI envisions a key role for local civil society organizations in holding governments accountable. Is that realistic in the West African context?

MT: Many civil society organizations are not necessarily independent, some receive government support and thus cannot criticize their government. This costs them credibility with broader society, it is a problem of accountability and trust. Also, local civil society organizations do not have the capacity to go out to sea and monitor illegal fishing; Greenpeace does have that capacity.

Some in Mauritania see the president's FiTI announcement as a hollow publicity stunt...

MT: There seems to be political will by the Mauritanian president [Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, who announced the global initiative in early 2015] and we have welcomed that. We applauded him for making the announcement; in future we will hold him accountable to his own words.

What concrete changes is Greenpeace advocating for?

JM: In relation to activities by European vessels outside EU waters, we want more transparency. There are already many strong rules in place for fishing inside EU waters. Now we need to make sure that the distant fleet also follows these. We want to see the phasing out of private agreements directly negotiated between commercial companies and foreign governments. And we are advocating for mechanisms that will ensure that all agreements with all countries set out the same standards, and are adhered to. Overall, transparency is key.

In the long term, developed countries should shift from seeking access agreements to concluding supporting agreements under which Africans themselves catch the fish in their own waters, within the sustainable levels, and European Union countries sustainably source their fish.

Note: This is the second in a series of fishy interviews I plan to publish on this blog over the coming weeks. The first, with Ba Aliou Coulibaly from Publish What You Pay in Mauritania, can be found here. If you are doing or researching fishy things in West Africa, please get in touch with me and share your insights, on or off the record.