I was able to chat recently with A.J. Walkley, my friend and a novelist, right before the launch of her newest book, Vuto. Set against the backdrop of Malawi, Africa, Walkley brings us the fictional account of Vuto, a 17-year-old who defies her entire village after losing her newborn baby. She finds herself completely alone in a world that had shielded her, but also a world that took her innocence away. Lost in her own grief, Vuto walks out on her old life only to be joined by American Peace Corps Volunteer Samantha, who becomes inspired by Vuto's powerful stand. With everything against them, they form an unlikely friendship that is played out in a series of narratives.

Drawing upon your experiences as a health volunteer with the Peace Corps in Malawi, Africa, what moments during that time inspired you to write Vuto?

The opening scene in which we meet Vuto, the title character, is taken straight out of my own experience witnessing a teenage girl give birth in the village I was stationed in as a Peace Corps health volunteer. It was such a raw, emotionless experience that has stuck with me for nearly six years now. I knew I had to write about it in some way. Without giving too much away, I also included Malawian puberty rites that both girls and boys in the villages often experience. I never witnessed such myself, but this custom involved all of the girls at the cusp of puberty in a village lining up outside of a hut in which an older male was stationed; in turn, each girl would enter the hut to be "deflowered" by the man. The same thing would occur with the boys of the village and an older female. I was shocked by this tradition, understanding it through my perspective as a Westerner. I have a feeling that will shock a lot of people.

Vuto seems to encompass many traits ingrained in her from Malawian customs. She is this fiercely independent young woman with this edginess to her; taught to be completely self-reliant from a young age and left to fend off "elders," but also seems to be just as vulnerable as a child. How were you able to paint such complexity and get into Vuto's head with these particular feelings?

For the character of Vuto, I drew a lot from one of the Malawian women I became very close with in the village I lived in as a volunteer - let's call her Lauren. She was not the typical villager, having gone into the city for some schooling, and as a result was much more outspoken than anyone else at the village level. It made me consider what the first Malawian feminist might look and act like. I tried to write Vuto as a mixture of the traits my Malawian friend Lauren had and those that a typical village woman might have as well -- tied to the place in which she was born and raised, yet thinking beyond that village to what the rest of the world might have to offer her as a woman, as a mother, as a global citizen.

Walkley with her homestay family in Malawi, Africa, at the end of Peace Corps training in 2007.

By writing a powerful lead for a Malawian woman that bows away from traditions in a society that still regards women as second-class citizens to a great extent, did you find that striking a balance to also make her relatable for a global audience was difficult?

I actually took the approach that, deep down, no matter where any of us is from, we are all human at the end of the day. No matter who you are, where you were born or what kind of upbringing you had, when one woman sees the pain of another woman losing their child -- that pain is universal. Speaking as an empathetic female, I can only imagine what losing not one, but three children in a row must feel like. The Peace Corps character, Samantha, relates to Vuto on a woman-to-woman basis. When Samantha learns of the three children Vuto has had to bury alone, as Malawian tradition dictates, she is unable to stand by and do nothing while Vuto mourns. I tried to strike a balance with both characters, hopefully painting a broader picture for readers about humanity both in Malawi and the United States.

While your two main characters -- Vuto and Samantha -- are polar opposites in many ways, we learn that they are very much the same as well. Can you talk about the main messages you hope to bring to readers with their roles, particularly with the moral dilemmas each character has to experience?

I think there are several messages I wanted to get across with the book as a whole, and the relationship between Vuto and Samantha specifically. As I mentioned before, I aimed to show how whatever differences may exist between the protagonists, their similarities as women trump them all. Vuto may not understand the idea of feminism, but she admires Samantha's ability to be outspoken; on the other hand, she also knows when Samantha should keep her mouth shut for the greater good. Samantha may not understand everything Vuto has experienced in her young life, but she empathizes with the loss of Vuto's children. Both women can meet in the middle of their individual cultural backgrounds to find common ground. I don't want to give too much away in terms of the specific moral dilemmas dealt with in the novel, but suffice to say that each character must come to terms with women's rights and the justice system in their own ways.

If not for your Peace Corps experience and your first-hand knowledge of Malawi, Vuto would not have been. Do you see yourself as an invisible character in the novel as you bring these two worlds that most people have not experienced to life in this story?

That's very true. In many ways I have inserted aspects of myself into many of the characters at different points in the novel, most notably Samantha. When I entered the Peace Corps, I was an incredibly naive college graduate who truly did not realize what life in Malawi for a health volunteer would be like. Even after the training I received on the ground, I still felt incredibly unprepared in many ways for service when I was dropped off at my site to serve alone. I attempted to put those feelings into Samantha, as well as the overwhelming idealism I entered the Peace Corps with and that I think many volunteers have when going into this field. That idealism soon left me when I realized just how big some of the issues the country was experiencing were and how ineffectual I could be.

I was very surprised at how you ended the novel. What do you want to leave readers with and do you feel hopeful that the youthful exuberance for idealism you give Samantha can truly exist? We saw it peak briefly in 2008 with Obama's election, but then we saw it take a dip. What type of societal message do you wish to send with Vuto?

Well I can't give away the ending, but I will say that in Vuto -- as in all of my novels -- I want to leave readers thinking. I want them to wonder, "What would I do if I were Vuto in this situation? Would I make the same decisions Samantha made?" As far as the idealism - I think it is always needed because in many ways, change cannot come without it in any area of the world, any industry. Sometimes it needs to be balanced with a dose of reality, but it must exist for our world to become a better place for all to live. In terms of a societal message, I think Vuto aims to get across the fact that change is possible, but takes time; that women's rights can look differently depending on where you are in the world; and that justice overseas can play out in ways that many are unaware of.

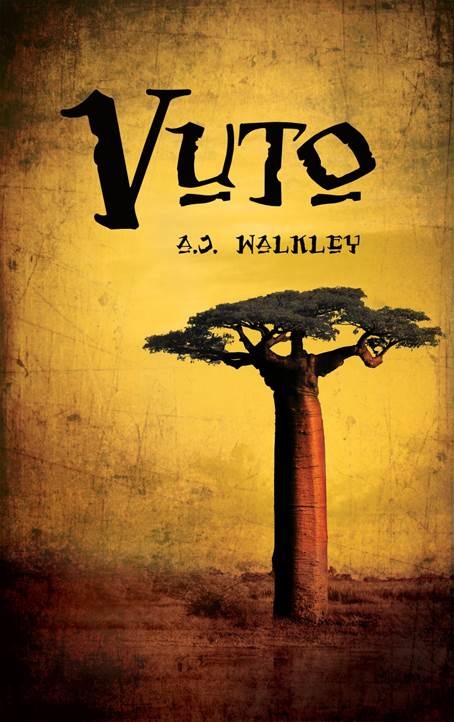

Vuto by A.J. Walkley comes out on July 22, 2013, and is available on Amazon.com.