BY ELISSA SCHAPPELL

"I prefer to think of myself as being inside a tangled knot; tangled knots fascinate me."

The Community Bookstore in Park Slope is not the sort of place you might imagine a West Side Story-style rumble to break out, and yet fans of the wildly successful epic meta-fiction novels of Elena Ferrante, author of the Neapolitan series, and Karl Ove Knausgaard, author of My Struggle, have on more than one occasion nearly come to blows. Not surprisingly, fans of Ferrante's innovative, swiftly moving, ruthlessly true-to-life tale of female friendship are quicker to the punch than fans of Knausgaard's languorously paced, nostalgic, navel-gazing domestic drama. Allegedly, glasses have been smashed, goatees set ablaze, and fountain pens unsheathed with the promise that, "I will shank you."

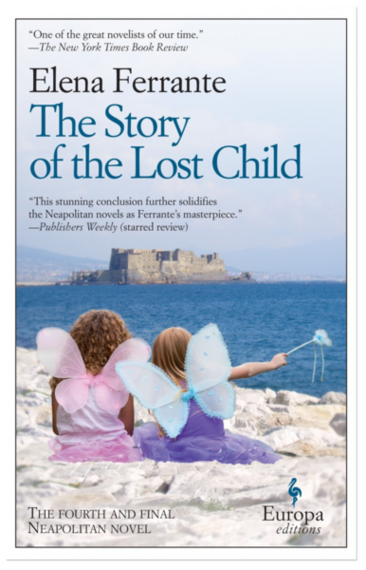

Passions run high when you're talking about Ferrante and her work, particularly her sensational, highly addictive Neapolitan novels, which paint a portrait of a consuming female friendship against the backdrop of social and political upheaval in Italy from the 1950s to the present day. My Brilliant Friend,The Story of a New Name, and Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay have made Ferrante, an enigmatic figure who writes under a pseudonym, and is widely regarded as the best contemporary novelist you've never heard of, a worldwide sensation. With the highly anticipated publication of the fourth and final book, The Story of the Lost Child, out this September, Ferrante fans are in a white-hot lather--and they should be.

For those not up to speed, Ferrante's unnervingly clear-eyed bildungsroman chronicles the lives of Elena Greco and Lila Cerullo, childhood friends who serve as each other's muse and champion, as well as each other's most punishing critic. Following them from their youth, as inseparable companions growing up in a poor crime-infested section of Naples, through years of love affairs, unsatisfying marriages, and careers, to the present. Where, battered by the disappointment and the demands of motherhood, and despite terminal jealousy, acts of betrayal, and mental illness, the two remain inextricably bound to each other. They will be, always, in orbit; one doesn't exist without the other. No other relationship in their lives possesses the intensity, longevity, or mystery of their friendship, and none will.

Now, Ferrante brings it all to a close in The Story of the Lost Child.

If readers of Ferrante's three previous Neapolitan novels wonder which one of these women was the brilliant friend, the end of The Lost Child leaves no question. This is Ferrante at the height of her brilliance.

My Brilliant Friend begins with a phone call from Lila's adult son informing Lena, now an acclaimed author of several books of autobiographical fiction, that his long-troubled mother has vanished. Since childhood, Lila had been terrorized by periodic lapses into a dissociative state, moments where the boundaries of herself and the world dissolve. Now, Lila has actually gone. In Book One, Lena maintains, "She wanted every one of her cells to disappear, nothing of her ever to be found, to leave not so much as a hair in the world." Lila has cut herself out of every family photo. She has left no note. And, as it's become clear to the reader, Lila would, if she could, destroy the novels that we have been reading.

The Story of the Lost Child begins, "From October 1976 until 1979, when I returned to Naples to live, I avoided resuming a steady relationship with Lila. But it wasn't easy."

No, it's not easy, not at all. Which is fantastic news for readers.

Had I the opportunity to address my questions to Ferrante, famously media shy and publicity intolerant, in person, instead of over e-mail, I would have done so, respectively, at her feet.

I am thrilled that the famously media-shy and publicity-intolerant Ferrante, who has a one-country-one-interview policy, was so generous with her time and insights. This is part one of a two-part interview, read part two here.

Vanity Fair: You grew up in Naples. It's been the setting for a number of your books--what is it about the city that inspires you?

Elena Ferrante: Naples is a space containing all my primary, childhood, adolescent, and early adult experiences. Many of my stories about people I know and whom I have loved come both from that city and in its language. I write what I know but I nurse this material in a disorderly way--I can only extract the story, invent it, if it appears blurred. For that reason, almost all of my books, even if they unfold today or are set in different cities, have Neapolitan roots.

Can we assume that the friendship between Lena and Lila is inspired by actual friendship?

Let's say that it comes from what I know of a long, complicated, difficult friendship that began at the end of my infancy.

The fact that Lena is telling the story, and that narrative subverts stereotypical notions of female friendship--friendship is forever, steady and uncomplicated--feels radical. What made you want to mine this material in this way?

Lena is a complex character, obscure to herself. She takes on the task of keeping Lila in the net of the story even against her friend's will. These actions seem to be motivated by love, but are they really? It has always fascinated me how a story comes to us through the filter of a protagonist whose consciousness is limited, inadequate, shaped by the facts that she herself is recounting, though she doesn't feel that way at all. My books are like that: the narrator must continually deal with situations, people, and events she doesn't control, and which do not allow themselves to be told. I like stories in which the effort to reduce experience to story progressively undermines the confidence of she who is writing, her conviction that the means of expression at her disposal are adequate, and the conventions that at the start made her feel safe.

Friendship between women can be particularly fraught. Unlike men, women tell each other everything. Intimacy is our currency, and as such, we are uniquely skilled in eviscerating each other.

Friendship is a crucible of positive and negative feelings that are in a permanent state of ebullition. There's an expression: with friends God is watching me, with enemies I watch myself. In the end, an enemy is the fruit of an oversimplification of human complexity: the inimical relationship is always clear, I know that I have to protect myself, I have to attack. On the other hand, God only knows what goes on in the mind of a friend. Absolute trust and strong affections harbor rancor, trickery, and betrayal. Perhaps that's why, over time, male friendship has developed a rigorous code of conduct. The pious respect for its internal laws and the serious consequences that come from violating them have a long tradition in fiction. Our friendships, on the other hand, are a terra incognita, chiefly to ourselves, a land without fixed rules. Anything and everything can happen to you, nothing is certain. Its exploration in fiction advances arduously, it is a gamble, a strenuous undertaking. And at every step there is above all the risk that a story's honesty will be clouded by good intentions, hypocritical calculations, or ideologies that exalt sisterhood in ways that are often nauseating.

Do you ever make a conscious decision to write against conventions or expectations?

I pay attention to every system of conventions and expectations, above all literary conventions and the expectations they generate in readers. But that law-abiding side of me, sooner or later, has to face my disobedient side. And, in the end, the latter always wins.

What fiction or nonfiction has most influenced you as a writer?

The manifesto of Donna Haraway, which I am guilty of having read quite late, and an old book by Adriana Cavarero (Italian title: Tu che mi guardi, tu che mi racconti). The novel that is fundamental for me is Elsa Morante's House of Liars.

One of the most striking aspects of the novels is the uncanny way you are able to capture the complexity of Lena and Lila's relationship without lapsing into cliché or sentimentality.

In general, we store away our experiences and make use of timeworn phrases--nice, ready-made, reassuring stylizations that give us a sense of colloquial normality. But in this way, either knowingly or unknowingly, we reject everything that, to be said fully, would require effort and a torturous search for words. Honest writing forces itself to find words for those parts of our experience that is crouched and silent. On one hand, a good story--or to put it better, the kind of story I like best--narrates an experience--for example, friendship--following specific conventions that render it recognizable and riveting; on the other hand, it sporadically reveals the magma running beneath the pillars of convention. The fate of a story that tends towards truth by pushing stylizations to their limit depends on the extent to which the reader really wants to face up to herself.

The unsparing, some might say brutally honest way you write about women's lives, your depictions of violence and female rage, as well as the intensity of feeling and the eroticism that can exist in female friendships, especially those between young women, is astonishingly spot on. Liberating. Given that we know how fraught and full of drama female friendships are, why do you think we don't read more books that depict these intense relationships more honestly?

Often that which we are unable to tell ourselves coincides with that which we do not want to tell, and if a book offers us a portrait of those things, we feel annoyed, or resentful, because they are things we all know, but reading about them disturbs us. However, the opposite also happens. We are thrilled when fragments of reality become utterable.

There is a "personal is political" brand of feminism running throughout your novels, do you yourself consider yourself a feminist? How would you describe the difference between American- and Italian-style feminism?

I owe much to that famous slogan. From it I learned that even the most intimate individual concerns, those that are most extraneous to the public sphere, are influenced by politics; that is to say, by that complicated, pervasive, irreducible thing that is power and its uses. It's only a few words, but with their fortunate ability to synthesize they should never be forgotten. They convey what we are made of, the risk of subservience we are exposed to, the kind of deliberately disobedient gaze we must turn on the world and on ourselves. But "the personal is political" is also an important suggestion for literature. It should be an essential concept for anyone who wants to write.

As to the definition of "feminist," I don't know. I have loved and I love feminism because in America, in Italy, and in many other parts of the world, it managed to provoke complex thinking. I grew up with the idea that if I didn't let myself be absorbed as much as possible into the world of eminently capable men, if I did not learn from their cultural excellence, if I did not pass brilliantly all the exams that world required of me, it would have been tantamount to not existing at all. Then I read books that exalted the female difference and my thinking was turned upside down. I realized that I had to do exactly the opposite: I had to start with myself and with my relationships with other women--this is another essential formula--if I really wanted to give myself a shape. Today I read everything that emerges out of so-called postfeminist thought. It helps me look critically at the world, at us, our bodies, our subjectivity. But it also fires my imagination, it pushes me to reflect on the use of literature. I'll name some women to whom I owe a great deal: Firestone, Lonzi, Irigaray, Muraro, Caverero, Gagliasso, Haraway, Butler, Braidotti.

In short, I am a passionate reader of feminist thought. Yet I do not consider myself a militant; I believe I am incapable of militancy. Our heads are crowded with a very heterogeneous mix of material, fragments of time periods, conflicting intentions that cohabit, endlessly clashing with one another. As a writer I would rather confront that overabundance, even if it is risky and confused, than feel that I'm staying safely within a scheme that, precisely because it is a scheme, always ends up leaving out lots of real stuff because it is disturbing. I look around. I compare who I was, what I have become, what my friends have become, the clarity and the confusion, the failures, the leaps forward. Girls like my daughters appear convinced that the freedom they've inherited is part of the natural state of affairs and not the temporary outcome of a long battle that is still being waged, and in which everything could suddenly be lost. As far as the male world is concerned, I have learned, contemplative acquaintances who tend either to ignore or to recast with polite mockery the literary, philosophical, and all other categories of work produced by women. That said, there are also very fierce young women, men who try to be informed, to understand, to sort through the countless contradictions. In short, cultural struggles are long, full of contradictions, and while they are happening it is difficult to say what is useful and what isn't. I prefer to think of myself as being inside a tangled knot; tangled knots fascinate me. It's necessary to recount the tangle of existence, both as it concerns individual lives and the life of generations. Searching to unravel things is useful, but literature is made out of tangles.

I've noticed that the critics who seem most obsessed by the question of your gender are men. They seem to find it impossible to fathom how that a woman could write books that are so serious--threaded with history and politics, and even-handed in their depictions of sex and violence. That the ability to depict the domestic world as a war zone and willingness to unflinchingly show women in an unflattering light are evidence that you're a man. Some suggest that not only are you a man, but given your output, you might be a team of men. A committee. (Imagine the books of the Bible...)

Have you heard anyone say recently about any book written by a man, It's really a woman who wrote it, or maybe a group of women? Due to its exorbitant might, the male gender can mimic the female gender, incorporating it in the process. The female gender, on the other hand, cannot mimic anything, for is betrayed immediately by its "weakness"; what it produces could not possibly fake male potency. The truth is that even the publishing industry and the media are convinced of this commonplace; both tend to shut women who write away in a literary gynaeceum. There are good women writers, not so good ones, and some great ones, but they all exist within the area reserved for the female sex, they must only address certain themes and in certain tones that the male tradition considers suitable for the female gender. It is fairly common, for example, to explain the literary work of women writers in terms of some variety of dependence on literature written by males. However, it is rare to see commentary that traces the influence of a female writer on the work of a male writer. The critics don't do it, the writers themselves do not do it. Thus, when a woman's writing does not respect those areas of competence, those thematic sectors and the tones that the experts have assigned to the categories of books to which women have been confined, the commentators come up with the idea of male bloodlines. And, if there's no author photo of a woman then the game is up: it's clear, in that case, that we are dealing with a man or an entire team of virile male enthusiasts of the art of writing. What if, instead, we're dealing with a new tradition of women writers who are becoming more competent, more effective, are growing tired of the literary gynaeceum and are on furlough from gender stereotypes. We know how to think, we know how to tell stories, we know how to write them as well as, if not better, than men.

Because girls grow up reading books by men, we are used to the sound of male voices in our heads, and have no trouble imagining the lives of the cowboys, sea captains, and pirates of he-manly literature, whereas men balk at entering the mind of a woman, especially an angry woman.

Yes, I hold that male colonization of our imaginations--a calamity while ever we were unable to give shape to our difference--is, today, a strength. We know everything about the male symbol system; they, for the most part, know nothing about ours, above all about how it has been restructured by the blows the world has dealt us. What's more, they are not even curious, indeed they recognize us only from within their system.

As a female writer I take offense at the idea that the only war stories that matter are those written by men crouched in foxholes.

Every day women are exposed to all kinds of abuse. Yet there is still a widespread conviction that women's lives, full of conflict and violence both in the domestic sphere and in all of life's most common contexts, cannot be expressed other than via the modules that the male world defines as feminine. If you step out of this thousand-year-old invention of theirs, you are no longer female.

More from Vanity Fair:

Mindy Kaling May or May Not Identify with Saddam Hussein

'You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine' and Our Obsession with Beauty Routines, Diet Diaries, and Chia Seeds

10 Great Movie Romances at the End of the World

We Talked Smoking, Drinking, and Soul-Baring with Alabama Shakes

What If They Discovered Sequels to Catcher in the Rye or On the Road?