"What size are you thinking?" the plastic surgeon asked.

I sat shirtless in the oversize, faux leather examining chair as he eyed the twin slits remaining on my chest four weeks after the mastectomy. I slipped a C-cup silicone breast prosthesis out of one side of the bra I'd worn into the office. "I used to be an A-cup. Can you match this?" He palmed the three-dimensional, triangular blob and then pressed it against one of my incisions, using the tips of his fingers to hold it in place. "I don't see why not. You're tall--you can carry any volume you want. Let's go with a 350 cc."

As a cancer patient, I felt a little sheepish asking for bigger breasts. I worried I was selling out to our society's beauty standard. But another part of me wanted the fun, sexiness, and visual appeal of a larger bustline.

The doctor wheeled backward on his stool, opened a drawer, and pulled out a crescent-shaped expander. I had liked him immediately. He seemed practical, matter-of-fact in the face of my cancer, the way I hoped in my best moments to be. He explained the surgery would involve placing two of these, filled with saline, in my chest to begin stretching the skin and muscle to shape mounds that would eventually house the implants.

After being diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer at age forty-three, I viewed my choice to have a mastectomy and then reconstruct my breasts as a privilege. My grandmother died of metastasized cancer in her forties. My mom had a lumpectomy and radiation following her diagnosis of cancer in her forties. I realized many women with more advanced breast cancer didn't have a choice of treatment options. Still, I wondered about the function my new breasts would serve. I no longer needed them for any practical purpose, such as breast-feeding. I would no longer derive the same sexual satisfaction from them, since they would be numb and my nipples were gone. Would they be purely cosmetic, as the title on my doctor's business card implied? If so, what was the right size for me?

A couple of weeks earlier, right after I'd had my post-mastectomy drainage tubes removed, I'd visited Mary Catherine's, a boutique in Seattle that specialized in mastectomy wear, to try on prostheses and bras.

A woman in her fifties in polyester pants and pink lipstick and bright white bouffant hair that flipped up in a curl once it passed her shoulders asked if she could assist me. I wondered if she was a breast cancer survivor herself. She led me to one of the changing rooms. I winced when a twinge of pain spiked across my chest as she helped me slip my shirt and camisole off. She asked me what size I'd like to try on. "Let's start with a C," I said.

As I waited, I glanced in the mirror and saw the two strips of surgical tape that remained over the horizontal incisions on my chest, and the tan lines from my pre-surgery trip to Hawaii that started at my shoulders and led to nowhere. The tan was fading, and my skin was beginning to peel off in little white flecks.

She brought in the first bra and a couple of boxes with different types of prostheses. "Most insurance covers the standard silicone--see how heavy that is. If you want to pay extra, you can get this new, whipped silicone, which is in the same shape, but much lighter and more comfortable to wear. Since you'll only be using yours for a couple of months, though, you'll probably just want to go with the standard."

I nodded in agreement and she showed me how to fold the heavier prosthesis like a taco to fit it into the pocket in the bra. She gently slid the bra straps over my arms and up on my shoulders and hooked it together in back, and I slipped my shirt on over it. The effect was too pointy and conelike -- more like what women wore in the 1950s. Next, please.

The next set I tried on felt more comfortable -- I liked the way I looked in the mirror.

"Why don't I try on a D just for the heck of it?" I asked the shop lady.

D felt too big on me -- I thought it made me look wider in my chest than I would naturally be. I settled on the second prosthesis I had tried, which was a full C-cup--one or two cup sizes bigger than I'd been just before the mastectomy and about the size I'd been in college, pre-kids.

As I thought about my ideal size in the dressing room, I tried to separate my own preference from the expectations of society, media, and men. Wasn't the purpose of reconstruction to replicate what you had lost?

I would never truly recover the physical part of what I had lost -- my breast tissue and my nipples. I would never again feel the water from the shower running down my breasts. I'd never again get goose bumps on my breasts when it was cold. I'd never again feel the pleasure of arousal when a man caressed my nipple. I'd forever miss seeing the original version of my body in the mirror.

Some would view reconstructive surgery as an opportunity to "improve" on what I'd lost. But that thought made me sad because I loved what I'd lost. I loved my small and droopy breasts, imperfect as they were. They were mine. I imagined I would feel detached in some way from the new breasts that the doctor would create. These wouldn't be the breasts I had been born to develop, which had served me so well.

Getting cosmetically improved fake breasts without any feeling was some small consolation after the mastectomy. But I would have the awareness every day that they weren't mine. I wouldn't be able to take credit for any approving glances I received in the future because of them. It would be like someone complimenting you on your smile when your teeth are covered with veneers.

I knew what middle-aged women's breasts were supposed to look like. I remembered sitting on my knees on shag carpet on sun-drenched afternoons thumbing through a stack of my parents' National Geographic magazines. The image of flaccid, elongated tissue with a surprisingly turned-up nipple on the end stayed with me. After using my breasts to nourish my infant son for a year, I hadn't expected them to pop back up to their pre-baby bounty. The replacements the surgeon could give me would not look natural in any real sense. They would be fuller and rounder than middle-aged women's breasts, regardless of the size I chose.

Now I sat, bare-topped and scarred, glancing over the plastic surgeon's shoulder at creamy brown walls holding strictly aligned, framed black-and-white photographs depicting nature's perfection: sailboats thrusting through currents and mountain ranges piercing cloudless skies.

I asked, "Why is there this myth that mastectomy is such an emotionally devastating surgery?"

"Because it's mutilating," he replied. "It's more like removing a hand than an appendix."

Because of my family's history of cancer, since my twenties I'd imagined what course I would take if I received the dreaded diagnosis one day. I got used to the idea that I might be part of this clan of women who got cancer early, just the latest generation to cope, and knew early on that I would choose to have my breasts removed. I was less shocked than some women about my diagnosis when it came and less anguished about making the treatment decision. I didn't view the possibility as any more difficult than the issues my friends would deal with in their midlife. By the time we hit our forties, we've all known pain -- it's been layered on us like so many coats of paint. Who's to say which heartbreak is the greatest: Losing a child or never having a romantic relationship? Surviving cancer or having a mentally ill son? All painful life events gouge deep furrows and cause emotions to bleed out of us -- shock, sorrow, and dismay. Through these tragedies, we are constantly rediscovering ourselves, peeling off the personas we've created to fit in socially and reaching for the unaltered seed of self within us. We'll never completely know our raw core -- never completely be able to separate the white of external influences from the yolk of our true selves. But we can ask the questions, keep on with the quest. In the quest for new breasts, my most surprising realization came as I sat in the plastic surgeon's office, flipping through binders of "before" pictures of anonymous women who had had mastectomies and chosen not to reconstruct. I was surprised at the depth of awe I felt. I respected those women most of all -- and recognized I wasn't there yet. I was still too reliant on society's expectations to forgo reconstruction after the mastectomy.

Why did I want new breasts and a larger cup size? For reasons of vanity. For my husband's sexual pleasure (since he'd be able to feel them and I wouldn't). And so I could deal privately with the emotional pain of removing my breasts by "passing" in society's eyes. I realized I hadn't chosen new, larger breasts after cancer solely to meet society's beauty standard. My new breasts would be more than cosmetic. They served a practical purpose. My new, larger breasts would be a reflection of the authentic me.

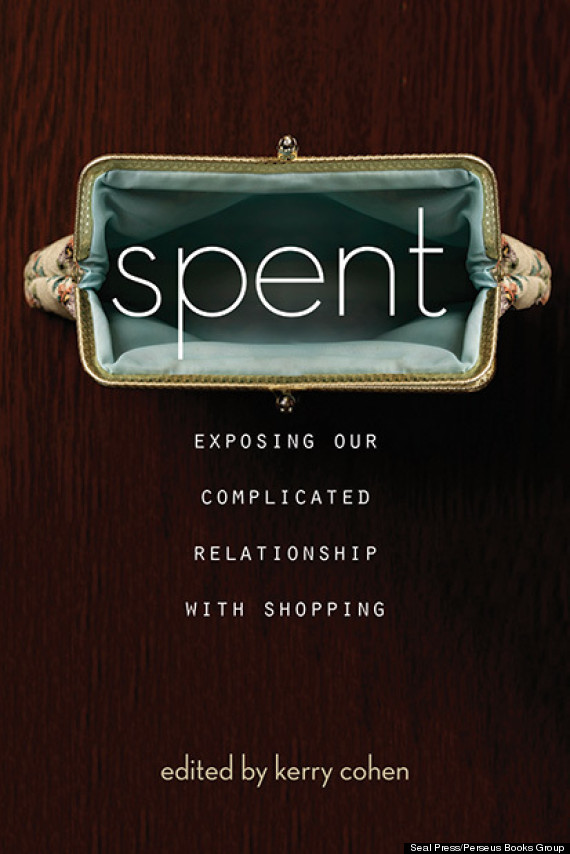

"Shopping For Breasts" by Wendy Staley Colbert is excerpted from Spent: Exposing Our Complicated Relationship with Shopping, edited by Kerry Cohen, with permission from Seal Press, a member of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2014. This article first appeared in Salon, a website located at www.salon.com.