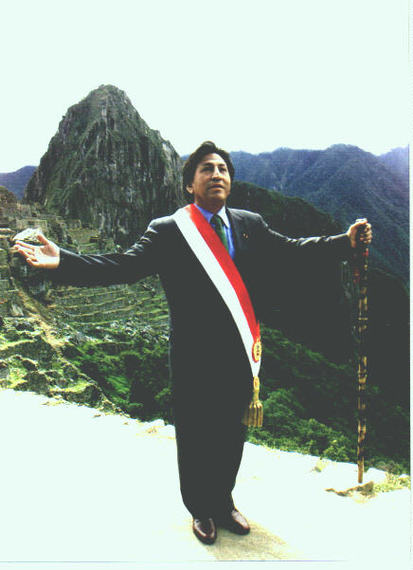

Former Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo told me, half-jokingly, that he exists in the error margin of the world of probabilities. Indeed, his rise shouldn't have been. Toledo doesn't just come from poverty. He was born of a poverty so dire, his siblings were dying of it. He is part of an indigenous family that lived 12,000 feet above sea level in the Andes. He was born amid serial-tragedy. The barriers to his upward mobility were not only dramatically material. They were also, in Peru, bluntly, irredeemably social--such is the dehumanizing racism of the Andean countries. Toledo is the first indigenous person to become a head of state in South America, and there are entrenched reasons why it was 500 years in coming.

And then there is also how Toledo rose. Toledo did not master a political machine to an eventual presidency founded on populism. There is nothing cliché about his achievements or precisely populist about his government. Instead, the former president strove academically first: beginning with a BA from the University of San Francisco to two MAs and a PhD from Stanford University. Toledo made his way through books and thought. He grinded it out in the libraries of America's most competitive and prestigious universities. Then, he took to the streets.

In Peru in 1996, at the height of a seemingly unrelenting dictatorship, he became the head of a street-rally movement for democracy. Subsequently, he was elected president and governed from 2001 to 2006--all without an iota of political experience. He was constitutionally barred to run immediately for reelection (a law he himself advocated for) but will be running again in Peru's general election next year. Toledo believes in a balanced agenda, calling for growth and social investment--the hallmarks of his own successful presidency. He nurtured a brisk growth averaging 6% by granting some strategic tax relief and a free-trade agreement with the United States. He also implemented free health-care for the poorest of the poor that endures today, with 15 million beneficiaries, and reduced extreme poverty by 25%.

After delivering some remarks and presenting his most recent book ("The Shared Society: A Vision for the Global Future of Latin America") at the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington, DC to a packed room, I had the privilege of sitting down with the former president. I prodded him with questions, trying to understand his ability to live and reconcile different worlds and come upon a perspective that might help others do the same: "You are getting deep into my life...but let me respond to your question," he said, adding:

"Nobody knows. This is the first time I'm going to reveal this: My mother had 22 children. And there were 6 miscarriages. And so we end up 16. Of the 16 that were born, 7 died the first year of their life because we didn't have access to potable water, sanitation, health care. And I'm #8, so I just narrowly made it. My father decided that we could not continue living at 5,000 meters above sea level in the Andes and decided to migrate. I suffered from early malnutrition, so I'm short. But by migrating at 4, 5 years old to a sea port where I nourished myself breakfast, lunch, and dinner on Omega 3 by necessity--I never knew what Omega 3 was--I recuperated a little bit of my mind."

The fact that Toledo hadn't shared this fact about his family life is surprising, since it speaks volumes about life in poverty--particularly Andean poverty. There are the killers you see, and those you don't: in the water, in the food. Ultimately, Toledo's father decided to leave his ancestral village that was literally killing his children through contaminated water and other privation. That difficult decision is the kind of leadership that Toledo himself talks about.

Now, Peru--and the region's--future hinges tantalizingly on good leadership. With a torrent of bad news around the world, Latin America has been a brighter spot and Peru has had a succession of capable and serious presidents. Toledo stresses, Latin America needs "leadership that has the courage to make decisions today thinking of our children and the children of our children, even if we don't see it, even if we don't benefit. We should be making decisions not thinking of the next election but rather thinking of the next generations."

Surely, Toledo's revelation about his lost siblings speaks to the essence of poverty alleviation and the importance of pushing the critical mass of a country's limited resources towards the new generation. There's no breaking the cycle without hitting key nutritional, hygienic and educational targets to benefit the youngest members of a population. The people who must benefit the most are those who are too young to vote.

Some of the improvements that Toledo instituted take time to bear fruit. And when you have resided in the margin of error for a large part of your natural life, you are mistaken for a miracle-maker. "People had enormous expectations. The first time an indigenous person with my background was elected in 500 years in South America. I was sentenced to not fail. So after 3 days of sitting in my chair, people came to the door of the palace and said, 'Cholo [a pejorative for an indigenous person that Toledo gives a jovial ring], you gave us democracy, now I need a job and need it now.' So I said, 'hold it, I'm just sitting here three days and there's no money...so it wasn't easy.' "

Clearly, Toledo has not had a lot of easy in his life. His escape reminds us how dire the consequences of failure can be. Indeed, no country or region is exempt from failure in its many forms--as America's own current problems illustrate. But Toledo's ascendance provides an alternate, boundless example of human nature and its misunderstood potential.