This piece comes to us courtesy of The Hechinger Report.

MILWAUKEE -- Before he could start student teaching in January at Sennette Middle School in nearby Madison, Andrew Johnson had to pass a multiple-choice test.

The 23-year-old wants to teach high-school science, so the exam he took tested his knowledge of biology, chemistry and physics. He had to know the basic properties of an atom and the difference between oxidation and combustion reaction.

But this spring, Johnson will take a practice version of a new performance assessment that goes beyond asking what he knows about his subject.

Formally known as the Teacher Performance Assessment, the portfolio-based assessment will be required for anyone completing a teacher-education program and seeking a teaching license in Wisconsin after August 31, 2015, the Department of Public Instruction has decided.

Johnson and teacher hopefuls in other states taking the Teacher Performance Assessment, even if for practice, will have to submit lesson plans, reflections of their work and a video of their classroom interactions with students as part of the web-based program.

All of it is aimed at answering a single, critical question: How well can you teach?

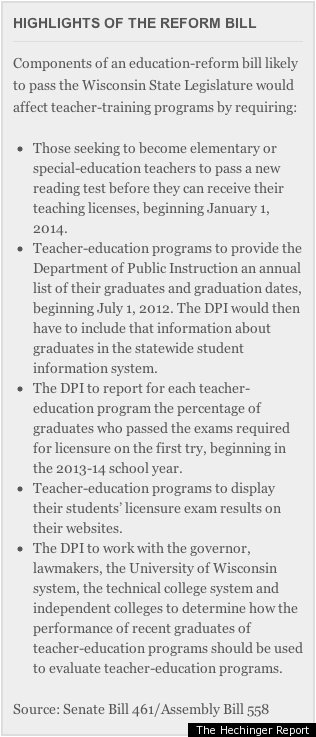

In Wisconsin, the impending assessment requirement dovetails with an education-reform bill pending in the state legislature. Combined, they constitute a major step toward improving the expectations and rigor of the state's teacher-training programs.

Like other states, Wisconsin is ramping up its focus on new teachers to ensure qualified people are entering the profession.

The end-goal is to boost overall student achievement, which has been stubbornly flat or declining for years in Wisconsin.

Most education-school leaders involved in the development of the new assessment support the changes, and say the current standards for future teachers and the institutions that train them could be strengthened.

For example, one state oversight practice includes making sure education schools have enough library books, a measure that does little to gauge whether they're turning out qualified teachers.

But several questions remain unanswered about the performance assessment in Wisconsin, such as what will constitute a passing score on the exam and whether any graduates will actually be denied a license because of their scores.

Also, some education-school leaders are skittish about a requirement in the proposed reform legislation that each preparation program publicize the percentage of its candidates who pass the certification exams on the first try. They see it as too narrow a gauge of program quality.

The assessment is being field-tested at three education schools in Wisconsin, which is one of 24 states testing or implementing the new assessment. More than 18,000 teachers-in-training will take the exam this spring.

To complete the assessment, teachers must plan, execute and document a specific lesson over three to five days. The evidence they submit as part of their portfolio includes those plans, as well as an in-class video and post-lesson reflection.

Developed by a team of researchers at Stanford University, the assessment will be administered by international education publishing and technology juggernaut Pearson.

Once teacher candidates submit their portfolios online, trained reviewers from around the country will grade them on a scale of 1 to 5.

They're looking for evidence of student learning, from the 10- to 15-minute video or teacher reflections.

A 3 or higher is typically considered a passing score, though Wisconsin hasn't settled on what its passing score will be.

"This is an intensive event that [student-teachers] cannot fake their way through," said Sheila Briggs, an assistant state superintendent at the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI).

"You really have to know how to be a teacher to demonstrate and pass that, and it gives us a better idea of how well a program is preparing its candidates to become teachers in the field."

Johnson, the student teacher in Madison, said he believes the new performance assessment will serve as a valuable tool.

"Passing the Praxis II just meant I had content knowledge," he said. "What's more important is for me to show I can convey that science knowledge to a class full of students."

Teachers in Wisconsin come from two types of training grounds: traditional education schools at four-year colleges or universities, such as the University of Wisconsin-Madison, or alternative-certification programs, such as Teach For America, that are designed to fast-track people who already have four-year degrees into the teaching profession.

The new performance assessment would be required of graduates from both types of programs. Currently, each institution decides individually how to assess the performance of its teachers.

The proposed education-reform legislation would require more data from teacher-training programs to be collected and published.

For example, in addition to publicly posting their graduates' first-time pass rates on the exams required for licensure starting in the 2013-14 school year, the programs would also have to provide the DPI an annual list of their graduates and graduation dates.

The DPI, in turn, would be required by the proposed legislation to include that data in a statewide student-information system, which could allow the state to track which schools new teachers end up in after graduation.

It could also eventually be connected to the performance of those teachers' students on state tests.

Teacher certification tests have been scrutinized because it's hard to adequately assess, in one exam, the multitude of skills necessary to be a good teacher. And there's little research evidence to suggest that the current crop of exams is a useful tool for doing that.

The current tests are developed by the nonprofit Educational Testing Service or the for-profit education company Pearson, and they typically rely heavily on multiple-choice questions.

Cut-scores, or the scores required to pass the tests, are often set well below averages.

A 2010 analysis by the National Council for Teacher Quality found that, on average, states had set the bar so low that even teacher candidates who scored in the 16th percentile would receive their certification.

In Wisconsin, the pass rate of new teachers on the multiple-choice subject tests required for licensure is 100 percent. That's because the state requires a passing grade on the test before an institution can recommend that teacher candidate for a license.

Nobody is currently required to report how many times a teacher candidate might have taken but failed the certification test.

"The testing technology that is widely used today just can't get at what is really the fundamental question of 'Can the person actually teach?' " said Sharon Robinson of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, which is collaborating with Pearson on the new performance assessment.

"We can give a number of different tests about what they know," she said. "I think the ambition now is to get an assessment that can actually document the candidate's ability to teach."

That means that candidates should be able to write and communicate in clear terms their ideas and intentions, Robinson said.

The National Council on Teacher Quality believes it's too early to say whether the Teacher Performance Assessment will be any better at assessing teacher quality than the current crop of certification tests.

Others have raised concerns about the cost of the assessment being an additional burden on college students trying to become teachers, an issue compounded by the fact that it's unclear if financial aid can be applied to the cost of the exam.

EARLY REVIEWS

In Wisconsin, three traditional education schools have been piloting the performance assessment: Alverno College in Milwaukee, UW-Madison and UW-Eau Claire.

Desiree Pointer Mace, assistant professor and associate dean for graduate programs at Alverno's School of Education, likes the assessment's layers: Teachers have to provide a written reflection of their teaching practice, and the 10- to 15-minute video gives some indication of how they interact in a classroom.

"It doesn't test what you can recall and push out; it tests the work of teaching and how you connect to students," Pointer Mace said. "Then the whole thing must be graded by someone who is independent but knows about teaching."

Alverno has long emphasized performance-based exams and the use of video as a tool for self-critique, so Pointer Mace said it's not a huge shift for the program to adapt to the new assessment.

But it is causing leaders to look at where they could improve courses to make sure teacher candidates are prepared for the exam, she said.

This semester will be the first time that student-teachers taking the assessment for practice in Wisconsin have their portfolios scored by independent, trained reviewers.

In previous trial runs, the assessments have been graded by the students' professors.

For the DPI, the assessment will also be used for continuously reviewing education schools.

"This is a brand new way of approving teacher-education programs in higher education," the DPI's Briggs said.

Briggs said that's going to shift the DPI from being an agency of regulatory oversight and technical assistance to an agency that is asking probing questions of teacher-education programs that make them think critically about how to make their programs better.

"We're not interested in jumping to decertify programs; we're more interested in identifying problems and helping them fix them," Briggs said. "Our goal is to bring everyone up."

Sarah Butrymowicz contributed to this report, a version of which appeared in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel on March 11, 2012.